World War II Combat Artists

in Charlestown

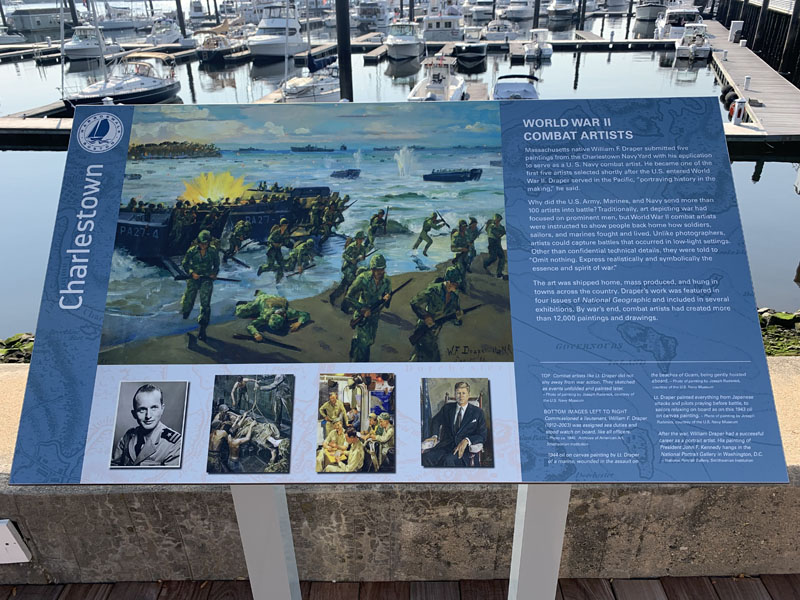

Combat artists like Lt. Draper did not shy away from war action. They sketched as events unfolded and painted later.

Photo of painting by Joseph Rudenick, courtesy of the U.S. Navy Museum

Massachusetts native William F. Draper submitted five paintings from the Charlestown Navy Yard with his application to serve as a U. S. Navy combat artist. He became one of the first five artists selected shortly after the U.S. entered World War II. Draper served in the Pacific, “portraying history in the making,” he said.

Why did the U.S. Army, Marines, and Navy send more than 100 artists into battle? Traditionally, art depicting war had focused on prominent men, but World War II combat artists were instructed to show people back home how soldiers, sailors, and marines fought and lived. Unlike photographers, artists could capture battles that occurred in low-light settings. Other than confidential technical details, they were told to “Omit nothing. Express realistically and symbolically the essence and spirit of war.”

The art was shipped home, mass produced, and hung in towns across the country. Draper’s work was featured in four issues of the National Geographic and included in several exhibitions. By war’s end, combat artists had created more than 12,000 paintings and drawings.

Sign Location

More …

Resources

- Charlestown Navy Yard Historic Resource Study, Stephen Carlson, National Park Service, sidebar on William F. Draper, p. 92.

- National Geographic, Aug 1943, April 1944, Oct 1944, and Nov 1945 (in NG archives).

- PBS documentary They Drew Fire, May 2000.

- PBS companion website for They Drew Fire

- William F. Draper obiturary, New York Times, Nov 1, 2003.

- Profile of William F. Draper

- For June 1977 oral history interview with William Draper

- For more of Draper’s work

Acknowledgments

- Warm thanks to NPS historian Steve Carlson for his help.

- Our gratitude to the Perkins School for the Blind and David W. Cook for their partnership in creating the audio files.