Ship Repair

in East Boston

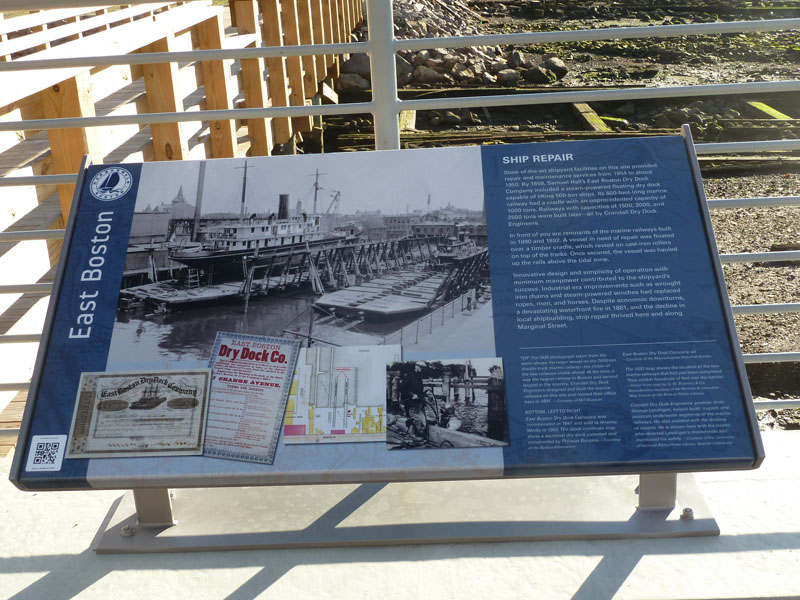

The 1928 photograph taken from the water shows the larger vessel on the 2000-ton double-track marine railway–the closer of the two railways visible ahead. At the time, it was the largest railway in Boston and second largest in the country. Crandall Dry Dock Engineers designed and built the marine railways on this site and moved their office here in 1891.

Photo courtesy of MIT Museum

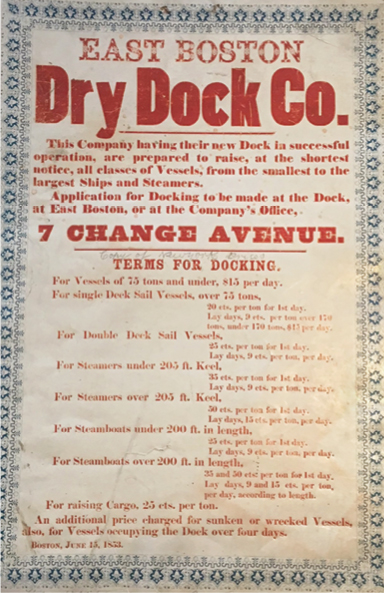

State-of-the-art shipyard facilities on this site provided repair and maintenance services from 1854 to about 1950. By 1858, Samuel Hall’s East Boston Dry Dock Company included a steam-powered floating dry dock capable of lifting 500-ton ships. Its 600-foot-long marine railway had a cradle with an unprecedented capacity of 1000 tons. Railways with capacities of 1500, 2000, and 2500 tons were built later–all by Crandall Dry Dock Engineers.

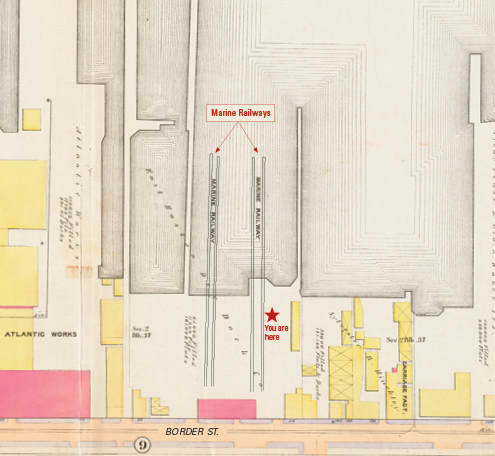

In front of you are remnants of the marine railways built in 1890 and 1892. A vessel in need of repair was floated over a timber cradle, which rested on cast-iron rollers on top of the tracks. Once secured, the vessel was hauled up the rails above the tidal zone.

Innovative design and simplicity of operation with minimum manpower contributed to the shipyard’s success. Industrial era improvements such as wrought iron chains and steam-powered winches had replaced ropes, men, and horses. Despite economic downturns, a devastating waterfront fire in 1861, and the decline in local shipbuilding, ship repair thrived here and along Marginal Street.

Crandall Dry Dock Engineers’ premier diver, George Landrigan, helped build, inspect, and maintain underwater segments of the marine railways. He also assisted with the docking of vessels. He is shown here with his tender, who directed Landrigan’s movements and monitored his safety.

Photo courtesy of the University of Vermont Bailey Howe Library, Special Collections

Sign Location

More …

Resources

- Public Archaeology Laboratory, Inc. Report t #3333 for Boston East, January 2018.

- Seasholes, Nancy & The Cecil Group. Sites for Historical Interpretation on East Boston’s Waterfronts. Boston: Boston Redevelopment Authority, 2009.

- Seasholes, Nancy. Gaining Ground: A History of Landmaking in Boston. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press, 2003.

- Sumner, William H. History of East Boston: With Biographical Sketches of its Early Proprietors, and an Appendix. Boston: William H. Piper and Company, 1858.

Acknowledgments

- Translation and recording thanks to the generosity of the Boston Marine Society

- Our gratitude to the Perkins School for the Blind and David W. Cook for their partnership in creating the audio files.