Many Forts, Many Uses

in South Boston

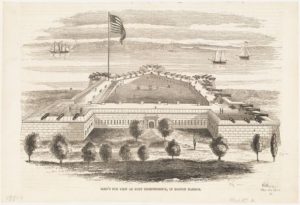

Today’s Fort Independence, completed in 1851, is Castle Island’s eighth fort.

Engraving courtesy of the Boston Public Library, Arts Department

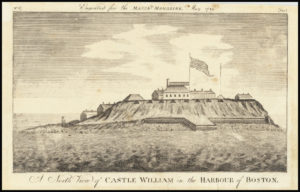

Castle Island’s strategic position alongside the narrow deepwater channel into Boston made it an ideal location to deter attacks. English colonists built the island’s first fort in 1634. They used what was readily available—timber and mud. Each fort that followed was sturdier than the one before. The present one is made of granite from Rockport, Massachusetts.

The island served a mix of military and civilian roles. Religious dissenters, deserters, and convicted criminals were among those imprisoned here. British officials and soldiers took refuge here from outraged Bostonians in the 1700s. The island was Boston’s inoculation facility during the 1764 small pox outbreak. And during World War II, Castle Island served as the location where the Navy demagnetized hundreds of U.S. warships to protect them from the enemy’s magnetic mines.

In 1962, the federal government transferred the fort and island to the Commonwealth of Massachusetts. Fort Independence is managed by the Department of Conservation and Recreation and is open on select summer days, with tours offered by Castle Island Association volunteers.

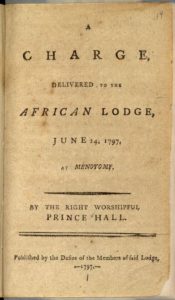

In March 1775, Prince Hall and 14 other men of color were inducted into a British Army Lodge of Freemasonry likely at Castle Island. Nine years later they formed the first Masonic African Lodge in the U.S. One of the most influential African-American activists of the late 1700s, Prince Hall advocated for an end to slavery and equal treatment for persons of color, notably in a widely published speech.

Cover of Prince Hall’s published 1797 speech courtesy of the Library of Congress

Sign Location

More …

Resources

- Allen, Danielle S. “A Forgotten Founder,” The Atlantic, March 2021.

- Bowen, James. Massachusetts in the War, 1861–1865. Clark W. Bryan & Co., 1889.

- Cary, John. Joseph Warren: Physician, Politician, Patriot. University of Illinois Press. 1964.

- Forman, Samuel A. Dr. Joseph Warren: The Boston Tea Party, Bunker Hill, and the Birth of American Liberty. Pelican Publishing Co., 2012.

- Gregory, A. F. Historic Fort Independence and Castle Island. Press of Louis F. Weston, 1908.

- Horton, James Oliver. Free People of Color: Inside the African American Community. The Smithsonian Institution, 1993.

- Horton, James Oliver and Lois E. Horton. Black Bostonians: Family Life and Community Struggle in the Antebellum North. Holmes & Meier, 1999.

- Reid, William J. Castle Island and Fort Independence. Trustees of the Public Library of the City of Boston, 1995.

- Schouler, William. A History of Massachusetts in the Civil War. E. P. Dutton & Co., 1868.

- Snow, Edward Rowe. Castle Island: Its 300 Years of History and Romance. Andover Press, 1935.

- About demagnetizing or degaussing http://indicatorloops.com/usn_pequot_magnetism.htm

Acknowledgments

This sign is made possible by funding from a Boston’s Community Preservation Act grant.

Warm thanks to historians at the Castle Island Association for their guidance and expertise in creating this sign and to the Department of Conservation and Recreation for their partnership.

Thank you to Brendan Albert and Kate Gutierrez for generously funding Spanish translations for the Castle Island/Pleasure Bay signs.

Our gratitude to the Perkins School for the Blind and David W. Cook for their partnership in creating the audio files.