El centro de Construcción Naval en Madera de Boston

in East Boston

Samuel H. Pook tenía 23 años cuando diseñó Surprise, el primero de varios de sus muy veloces clippers y uno de los clippers más activos en el comercio con China. Más adelante, Pook se convirtió en arquitecto naval de la Armada de los Estados Unidos.

Surprise by Xanthus Russell Smitth, photo courtesy of the Home of Franklin D. Roosevelt National Historic Site, National Park Service

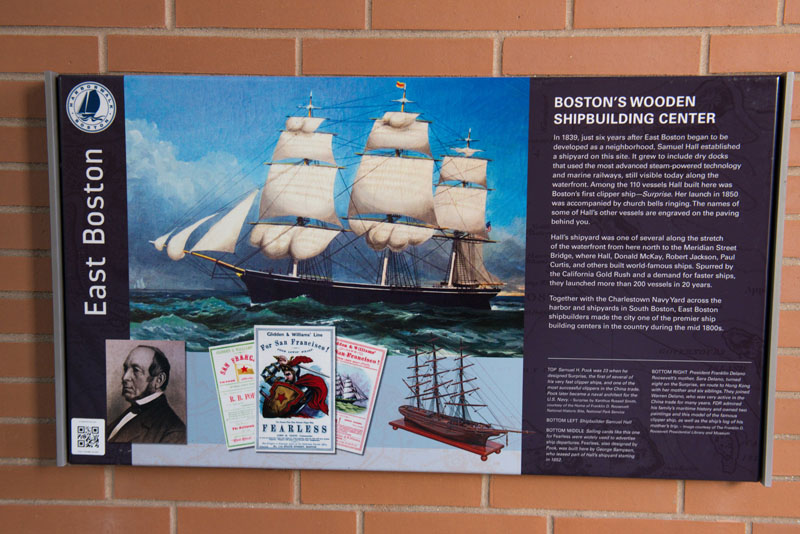

En 1839, apenas seis años después de que East Boston comenzara a desarrollarse como barrio, Samuel Hall estableció un astillero en este sitio. Se expandió hasta incluir diques secos que utilizaban la tecnología de vapor más avanzada, y también varaderos, representados en la acera detrás de usted. Entre las 110 embarcaciones construidas por Hall en este lugar, se encontraba el primer clipper de Boston, Surprise. Su botadura en el año 1850 fue acompañada por el sonar de campanas de iglesia. Los nombres de algunas de las otras embarcaciones de Hall están grabados en los adoquines de granito.

El astillero de Hall era uno de varios que se encontraban a lo largo de la costa desde aquí hacia el norte hasta el puente de la calle Meridian, donde Hall, Donald McKay, Robert Jackson, Paul Curtis y otros construyeron embarcaciones de fama mundial. Impulsados por la fiebre del oro en California y la demanda de barcos más rápidos, botaron más de 200 embarcaciones en 20 años.

Junto con el astillero de Charlestown Navy Yard al otro lado del puerto y los astilleros de South Boston, los constructores navales de East Boston convirtieron a la ciudad en uno de los principales centros de construcción naval del país a mediados del siglo XIX.

Sara Delano, la madre del presidente Franklin Delano Roosevelt, cumplió ocho años a bordo del Surpirse cuando estaba en camino a Hong Kong con su madre y seis hermanos. Iban a encontrarse con Warren Delano, quien trabajó activamente en el comercio con China durante muchos años. FDR sentía admiración por la historia marítima de su familia y tenía dos pinturas y este modelo del famoso clipper. También tenía la bitácora del viaje de su madre.

Photo courtesy of the Franklin D. Roosevelt Presidential Library and Museum

Ubicación del Cartel

Más…

Recursos (en inglés)

- Bunting, W.H. Portrait of a Port: Boston, 1852-1914. Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press, Harvard University Press, 1971.

- Clark, Arthur. The Clipper Ship Era. G.P. Putman’s Sons, 1911.

- Cross, Robert. Sailor in the White House: Seafaring Life of FDR. Naval Institute Press, 2003.

- “East Boston Waterfront District Municipal Harbor Plan,” prepared by The Cecil Group for Boston Redevelopment Authority, May 2008.

- Morrison, Samuel Eliot. The Maritime History of Massachusetts, 1783–1860. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Co., 1961 edition.

- Seasholes, Nancy & The Cecil Group. Sites for Historical Interpretation on East Boston’s Waterfronts. Boston: Boston Redevelopment Authority, 2009.

- Seasholes, Nancy. Gaining Ground: A History of Landmaking in Boston. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press, 2003.

- Sumner, William H. History of East Boston: With Biographical Sketches of its Early Proprietors, and an Appendix. Boston: William H. Piper and Company, 1858.

- about Samuel Hall

- FDR-Surprise link & Delano family China trade

- FDR’s grandfather’s involvement in China trade; FDR Presidential Library & Museum and Hudson River Valley Heritage

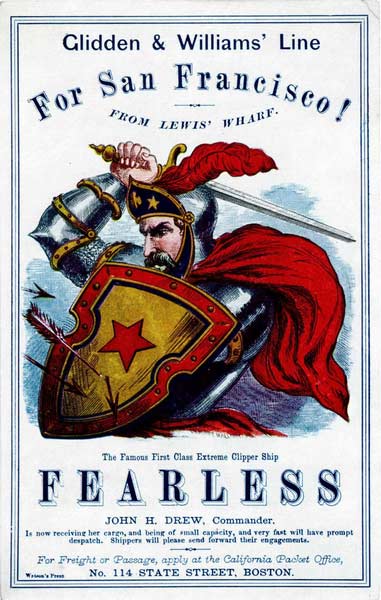

- about sailing cards

Agradecimientos (en inglés)

- Translation and recording thanks to the generosity of the Boston Marine Societ

- Our gratitude to the Perkins School for the Blind and David W. Cook for their partnership in creating the audio files.