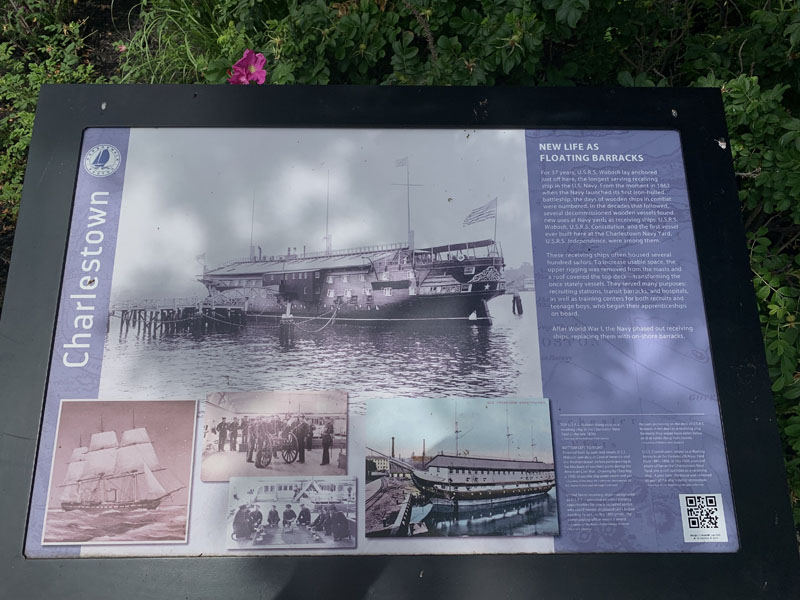

New Life as Floating Barracks

in Charlestown

U.S.R.S. Wabash doing duty as a receiving ship in the Charleston Navy Yard in the late 1870s.

Courtesy of the National Park Service

For 37 years, U.S.R.S. Wabash lay anchored just off here, the longest serving receiving ship in the U.S. Navy. From the moment in 1862 when the Navy launched its first iron-hulled battleship, the days of wooden ships in combat were numbered. In the decades that followed, several decommissioned wooden vessels found new uses at Navy yards as receiving ships. U.S.R.S. Wabash, U.S.R.S. Constitution, and the first vessel ever built here at the Charlestown Navy Yard, U.S.R.S. Independence, were among them.

These receiving ships often housed several hundred sailors. To increase usable space, the upper rigging was removed from the masts and a roof covered the top deck—transforming the once stately vessels. They served many purposes: recruiting stations, transit barracks, and hospitals, as well as training centers for both recruits and teenage boys, who began their apprenticeships on board.

After World War I, the Navy phased out receiving ships, replacing them with on-shore barracks.

Powered both by sails and steam, U.S.S. Wabash saw duty in Central America and the Mediterranean before participating in the blockade of southern ports during the American Civil War. Drawing by Clary Ray, c. 1900, shows the ship under steam and sail.

Courtesy of the Navy Art Collection, Washington, DC. U.S. Naval History and Heritage Command

United States receiving ships—designated as U.S.R.S.—provided excellent training opportunities for newly recruited sailors who could master shipboard skills before heading to sea. In this 1883 photo, the commanding officer wears a sword.

Courtesy of the Boston Public Library, Pictorial Archive Collection

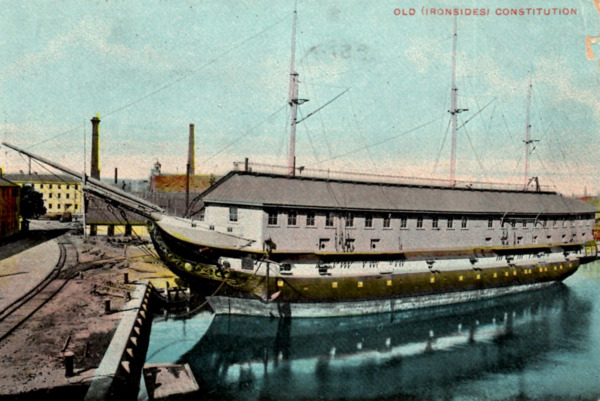

U.S.S. Constitution served as a floating barracks at the Portsmouth Navy Yard from 1881–1896. In this 1906 postcard photo of her in the Charlestown Navy Yard, she is still outfitted as a receiving ship. A year later the house was removed as part of the ship’s initial restoration.

Courtesy of the Stephen Landrigan collection

Sign Location

More …

Resources

- Carlson, Stephen. Charlestown Navy Yard Historic Resource Study, Volumes 1 & 2. Boston National Historical Park, National Park Service, 2010.

Acknowledgments

- Translation and recording thanks to the generosity of the Boston Marine Society

- Our gratitude to the Perkins School for the Blind and David W. Cook for their partnership in creating the audio files