Boston’s Wooden Shipbuilding Center

in East Boston

Samuel H. Pook was 23 when he designed Surprise, the first of several of his very fast clipper ships, and one of the most successful clippers in the China trade. Pook later became a naval architect for the U.S. Navy.

Surprise by Xanthus Russell Smitth, photo courtesy of the Home of Franklin D. Roosevelt National Historic Site, National Park Service

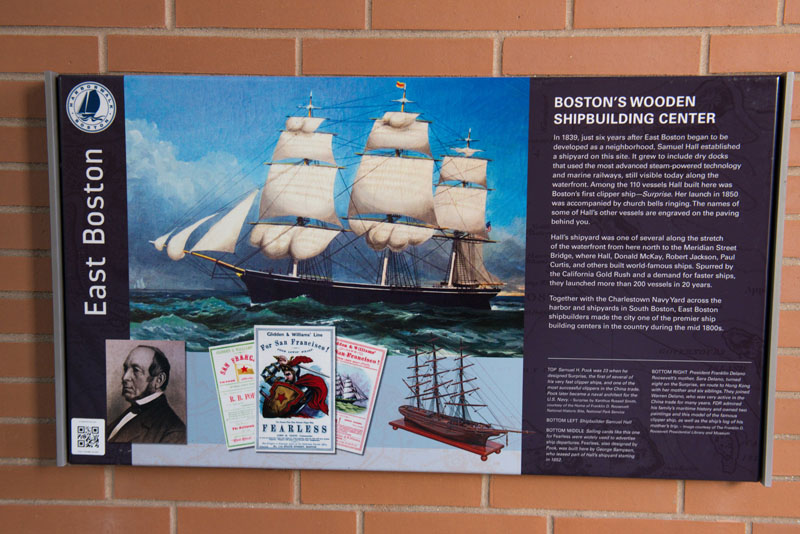

In 1839, just six years after East Boston began to be developed as a neighborhood, Samuel Hall established a shipyard on this site. It grew to include dry docks that used the most advanced steam-powered technology and marine railways, still visible today along the waterfront. Among the 110 vessels Hall built here was Boston’s first clipper ship–Surprise. Her launch in 1850 was accompanied by church bells ringing. The names of some of Hall’s other vessels are engraved on the granite paving.

Hall’s shipyard was one of several along the stretch of the waterfront from here north to the Meridian Street Bridge, where Hall, Donald McKay, Robert Jackson, Paul Curtis, and others built world-famous ships. Spurred by the California Gold Rush and a demand for faster ships, they launched more than 200 vessels in 20 years.

Together with the Charlestown Navy Yard across the harbor and shipyards in South Boston, East Boston shipbuilders made the city one of the premier ship building centers in the country during the mid 1800s.

President Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s mother, Sara Delano, turned eight on the Surprise, en route to Hong Kong with her mother and six siblings. They joined Warren Delano, who was very active in the China trade for many years. FDR admired his family’s maritime history and owned two paintings and this model of the famous clipper ship, as well as the ship’s log of his mother’s trip.

Photo courtesy of the Franklin D. Roosevelt Presidential Library and Museum

Sign Location

More …

Resources

- Bunting, W.H. Portrait of a Port: Boston, 1852-1914. Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press, Harvard University Press, 1971.

- Clark, Arthur. The Clipper Ship Era. G.P. Putman’s Sons, 1911.

- Cross, Robert. Sailor in the White House: Seafaring Life of FDR. Naval Institute Press, 2003.

- “East Boston Waterfront District Municipal Harbor Plan,” prepared by The Cecil Group for Boston Redevelopment Authority, May 2008.

- Morrison, Samuel Eliot. The Maritime History of Massachusetts, 1783–1860. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Co., 1961 edition.

- Seasholes, Nancy & The Cecil Group. Sites for Historical Interpretation on East Boston’s Waterfronts. Boston: Boston Redevelopment Authority, 2009.

- Seasholes, Nancy. Gaining Ground: A History of Landmaking in Boston. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press, 2003.

- Sumner, William H. History of East Boston: With Biographical Sketches of its Early Proprietors, and an Appendix. Boston: William H. Piper and Company, 1858.

- about Samuel Hall

- FDR-Surprise link & Delano family China trade

- FDR’s grandfather’s involvement in China trade; FDR Presidential Library & Museum and Hudson River Valley Heritage

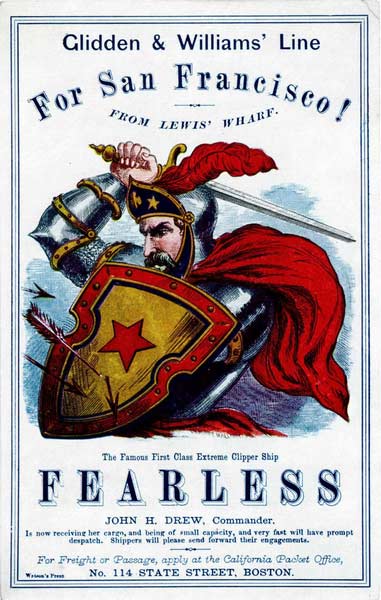

- about sailing cards

Acknowledgments

- Translation and recording thanks to the generosity of the Boston Marine Society

- Our gratitude to the Perkins School for the Blind and David W. Cook for their partnership in creating the audio files.