A Changing Channel

in South Boston

Traffic came to a halt as sugar boat SS Evelyn was towed through the Congress Street Bridge in 1929. Soon a bascule bridge that pivoted up replaced the swing-span bridge. The new bridge eliminated the center drum, allowing a 75-foot opening.

Courtesy of the Boston Public Library, Leslie Jones Collection

Originally a natural deepwater channel, Fort Point Channel was defined in the 19th century by land created on both sides. It was a thriving industrial waterway for years before it declined in the 20th century.

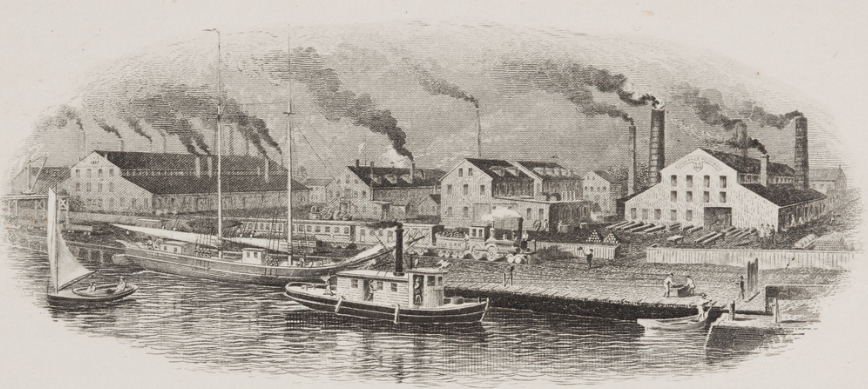

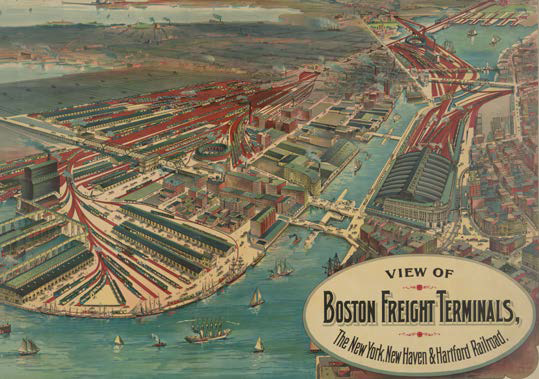

Industries flocked to the newly made land. Iron foundries, sugar refineries, and machine shops clustered on this side of the channel. The leather industry settled on the other. The channel teemed with boats bringing raw materials, such as lumber, bricks, and cement, to growing industrial and residential areas. Sugar and molasses were delivered to one-story warehouses located here and nearby. Coal was distributed widely by boat and train to fuel steam engines running factory machinery and later electrical plants.

Drawbridges across the channel improved access to South Boston industries but slowed boat traffic. New rail lines and piers like Fan Pier along the harbor reduced the channel’s use, as did filling South Bay. In the 1950s, when the bridges were fixed in place, shipping on the channel ended. Today, new development along this historic waterway is spurring its revitalization as a recreational and cultural destination.

Fashionable Bostonians enjoyed strolling on the South Boston Bridge in the 1820s before heavy industry prevailed. The bridge stood between what was known as South Bay to the south and the Fort Point Channel to the north. It is now West 4th Street where the channel ends in a culvert below.

Courtesy of the Boston Athenaeum

Sign Location

More …

Resources

- Bennett, Lola. Historic American Engineering Record: Summer Street Bridge: HAER NO. MA-135. National Park Service, 1995.

- Carolan, Jane. Historic American Engineering Record: Fort Point Channel: HAER NO. MA-130. National Park Service, 1995.

- Clement, Dan and Peter Stott. Historic American Engineering Record: Congress Street Bascule Bridge: HAER NO. MA-38. National Park Service, 1984.

- Clement, Dan and Peter Stott. Historic American Engineering Record: New York, New Haven and Hartford Railroad Fort Point Channel Rolling Lift Bridge: HAER NO. MA-35. National Park Service, 1984.

- “Fort Point Channel Activation Plan.” City of Boston, 2002.

- The Fort Point Channel Landmark District: Boston Landmarks Commission Study Report. City of Boston, 2009.

- Hollinger, Steve. Boston’s Fort Point District: A Landmark of New England’s Maritime and Industrial Past. Boston Landmark Commission, 2001.

- Leather District: National Registration of Historic Places Inventory Nomination Form. U.S. Department of Interior Heritage Conservation and Recreation Service, 1980.

- Massachusetts Historical Commission Reconnaissance Survey Town Report Boston, 1981.

- Seasholes, Nancy S. Gaining Ground: A History of Landmaking in Boston. The MIT Press, 2003.

- Stott, Peter. “Economic and Industrial Development.” Historical and Archaeological Resources of the Boston Area: A Framework for Preservation Decisions. Massachusetts Historical Commission, 1982.

- Stott, Peter. A Guide to the Industrial Archaeology of Boston Proper. The MIT Press, 1984.

- Stott, Peter, South Boston. Draft industrial archeology report on firms in South Boston, On file at Massachusetts Historical Commission.

- Tyrrell, Michael J. Boston’s Fort Point District. Arcadia Publishing, 2003.

Acknowledgments

- Warm thanks to Nancy Seasholes for her reliable assistance.

- A special thank you to Peter Stott, who graciously provided access to an unpublished paper and patiently answered questions about work he’d completed decades ago.

- Our gratitude to the Perkins School for the Blind Recording Studio and Thomasine Berg for their partnership in creating the audio files.