Outrage on the Eastern

in East Boston

(awaiting installation)

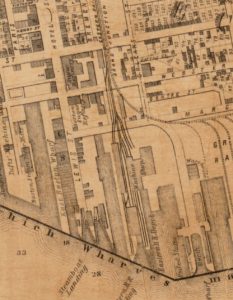

An Eastern locomotive at the East Boston waterfront terminal, c. 1860. The Eastern Railroad was one of several Massachusetts rail lines built in the 1830s and 40s.

Courtesy of Historic Beverly

The Eastern Railroad opened in 1838 with its Boston terminal at this site. It was one of America’s first rail lines and one of the first to separate passengers by race. In the 1840s, Black abolitionists, who not only worked to end slavery in the South, but also fought for equal rights in Massachusetts, challenged the Eastern’s policy.

On September 30, 1841, Mary Newhall Green, a Black woman traveling with her infant child, was ordered by an Eastern conductor to sit in the train’s “Jim Crow car.” She refused. Railroad employees dragged her from the train as she held her baby, injuring her shoulder and knee. Later that day, a Black man boarded a whites-only car in East Boston. He was also pulled from the train along with five white passengers who objected to his removal.

These and other acts of resistance sparked a movement to eliminate Jim Crow cars on Massachusetts railroads. Through newspaper coverage, boycotts, and petitions to the state legislature, this campaign eventually forced the Eastern’s board of directors to desegregate the railroad in 1843.

“I need no prompting. I hope that I have intelligence and courage enough to assert my rights when I see them invaded.”

Mary Newhall Green, Secretary of the Lynn Female Anti-Slavery Society, responded to accusations that she did not act of her own accord in an open letter to the directors of the Eastern Railroad, November, 1841.

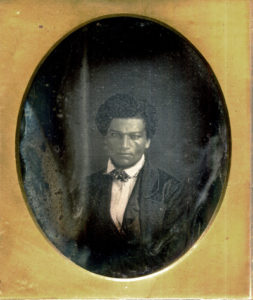

In early September, 1841, 23-year-old Frederick Douglass, a member of the Massachusetts Anti-Slavery Society, was dragged from an Eastern train and beaten for refusing to move to a “Jim Crow car.” Three weeks later, he again boarded a whites-only car, but this time he was prepared, taking hold of his seat as six men grabbed him. He later wrote: “In dragging me out, on this occasion, it must have cost the company twenty-five or thirty dollars, for I tore up seats and all.”

c.1841 daguerreotype, courtesy of the Collection of Greg French

A ferry transported passengers between downtown and the Eastern’s terminal here. The line eventually connected to Portland, Maine. In 1890 the Eastern was purchased by the Boston & Maine Railroad. Today, the Mary Ellen Welch Greenway follows the railroad’s old right of way through East Boston. Further north, portions are still used by MBTA commuter trains.

R. H. Eddy & John Noble, Plan of East Boston, 1851. Courtesy of the Leventhal Map & Education Center at Boston Public Library

Sign Location

More ...

Resources

-

Archer, Richard. Jim Crow North: The Struggle for Equal Rights in Antebellum New England (New York: Oxford University Press, 2017).

-

Bradlee, Francis B. C. The Eastern Railroad: A Historical Account of Early Railroading in New England, 2nd Edition (Salem, MA: The Essex Institute, 1922).Collins, J. A. “Eastern Rail-Road — Colorphobia — Lynch Law — Robbery — Quakerism.” The Liberator, Vol. XI, No. 42, October 15, 1841.

-

Douglass, Frederick. My Bondage and My Freedom. (New York: Penguin Books, 2003).

-

“Eastern Rail-Road Outrage.” The Liberator, Vol. XI, No. 45, November 11, 1841.

- Georges, Danielle Legros. Boston Black Heritage Trail Walking Tour, “The Geography of Belonging,” Boston Globe Magazine, May 2, 2021.

-

Luxenberg, Steve. Separate: The Story of Plessy v. Ferguson, and American’s Journey from Slavery to Segregation (New York: W. W. Norton & Company, 2020).

-

Ruchames, Louis. “Jim Crow Railroads in Massachusetts”. American Quarterly, Vol. VIII, No. 1 (Spring 1956).

-

“Traveller’s Directory.” The Liberator, Vol. XII, No. 38, September 23, 1842.

Acknowledgments

Warm thanks to Steve Luxenberg and professors Robert Allison and John Stauffer for their review of this sign.