Exploring the Living Shoreline

in East Boston

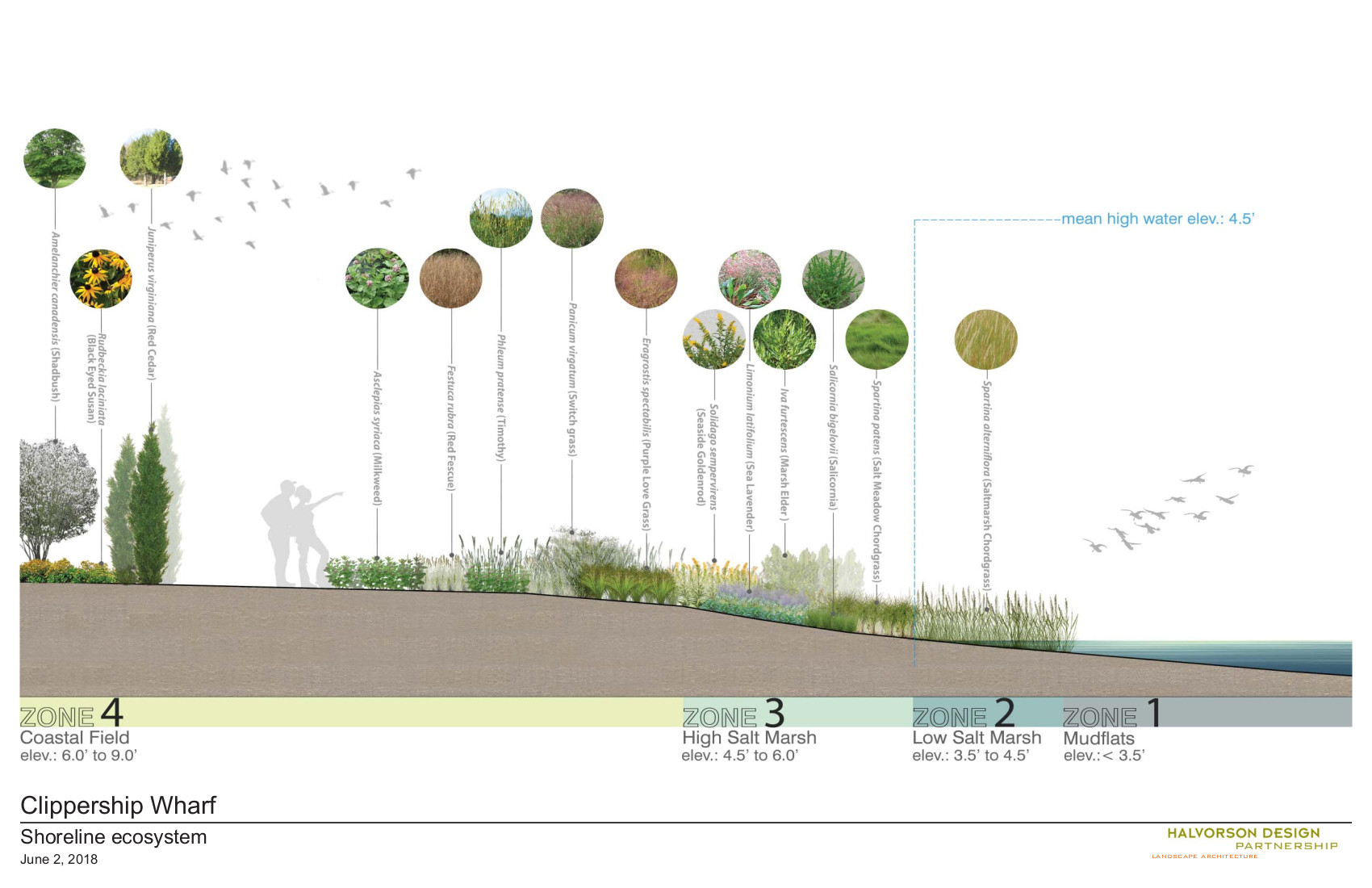

Saltmarsh chordgrass (Spartina alterniflora) and saltmeadow cordgrass (Spartina patens) were the original plant species introduced into the low and high marsh. Many additional plants now call the Living Shoreline home. How many can you identify?

Much of Boston’s shoreline between high and low tide—the intertidal zone—was lost during the 19th century, when the city was the second largest port in the country. Sea trade, ship building, and related industries dominated and changed the waterfront to fit their needs. Living shorelines recreate the intertidal zone. This one is the first such project along Boston’s Harborwalk and an alternative solution to shorelines in urban areas.

The project design transformed approximately 24,000 square feet into the new, diverse wetland community you see in front of you. Portions of the shoreline were terraced to create flat areas at different elevations. Each terrace attracts specific plants, depending on how much time they need to spend under water as the tide flows in and out. A greater diversity of plants lives on the upper terraces.

Below the marsh grasses, various animals thrive in the tide pools. Common periwinkles, blue mussels, sea urchins, northern moon snails, and sea stars feed and take shelter in the vegetation. Sea birds, in turn, feast on the animals living in the grasses. Together they create a vibrant ecosystem.

Sign Location

More …

Resources

No resources at this time.

Acknowledgments

- Translation and recording thanks to the generosity of the Boston Marine Society

- Our gratitude to the Perkins School for the Blind and David W. Cook for their partnership in creating the audio files.