Putting the Pier to Work

in South Boston

(awaiting installation)

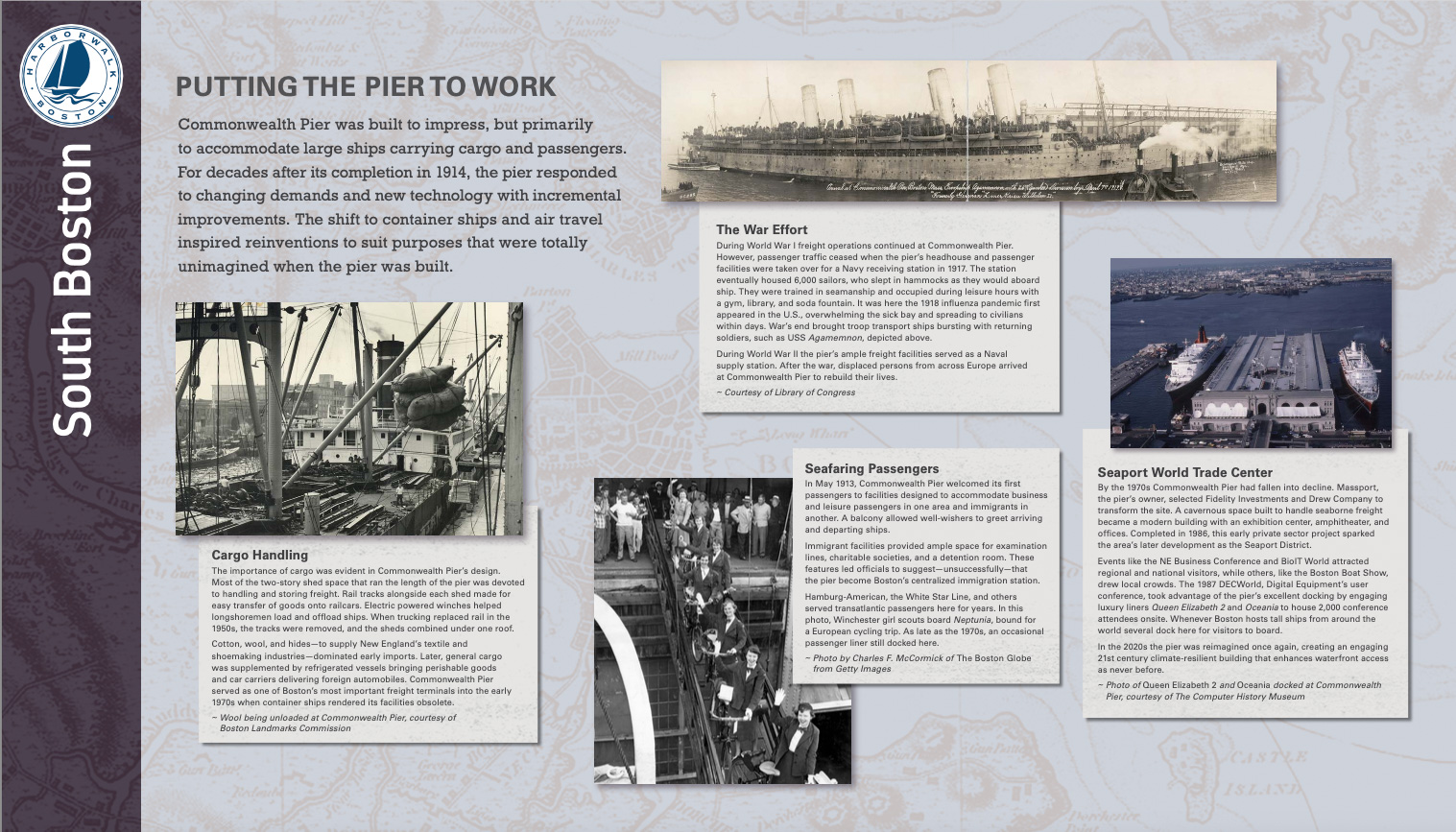

Commonwealth Pier was built to impress, but primarily to accommodate large ships carrying cargo and passengers. For decades after its completion in 1914, the pier responded to changing demands and new technology with incremental improvements. The shift to container ships and air travel inspired reinventions to suit purposes that were totally unimagined when the pier was built.

Cargo Handling

The importance of cargo was evident in Commonwealth Pier’s design. Most of the two-story shed space that ran the length of the pier was devoted to handling and storing freight. Rail tracks alongside each shed made for easy transfer of goods onto railcars. Electric powered winches helped longshoremen load and offload ships. When trucking replaced rail in the 1950s, the tracks were removed, and the sheds combined under one roof.

Cotton, wool, and hides—to supply New England’s textile and shoemaking industries—dominated early imports. Later, general cargo was supplemented by refrigerated vessels bringing perishable goods and car carriers delivering foreign automobiles. Commonwealth Pier served as one of Boston’s most important freight terminals into the early 1970s when container ships rendered its facilities obsolete.

The War Effort

During World War I freight operations continued at Commonwealth Pier. However, passenger traffic ceased when the pier’s headhouse and passenger facilities were taken over for a Navy receiving station in 1917. The station eventually housed 6,000 sailors, who slept in hammocks as they would aboard ship. They were trained in seamanship and occupied during leisure hours with a gym, library, and soda fountain. It was here the 1918 influenza pandemic first appeared in the U.S., overwhelming the sick bay and spreading to civilians within days. War’s end brought troop transport ships bursting with returning soldiers, such as USS Agamemnon, depicted above.

During World War II the pier’s ample freight facilities served as a Naval supply station. After the war, displaced persons from across Europe arrived at Commonwealth Pier to rebuild their lives.

Seafaring Passengers

In May 1913, Commonwealth Pier welcomed its first passengers to facilities designed to accommodate business and leisure passengers in one area and immigrants in another. A balcony allowed well-wishers to greet arriving and departing ships.

Immigrant facilities provided ample space for examination lines, charitable societies, and a detention room. These features led officials to suggest—unsuccessfully—that the pier become Boston’s centralized immigration station.

Hamburg-American, the White Star Line, and others served transatlantic passengers here for years. In this photo, Winchester girl scouts board Neptunia, bound for a European cycling trip. As late as the 1970s, an occasional passenger liner still docked here.

Seaport World Trade Center

By the 1970s Commonwealth Pier had fallen into decline. Massport, the pier’s owner, selected Fidelity Investments and Drew Company to transform the site. A cavernous space built to handle seaborne freight became a modern building with an exhibition center, amphitheater, and offices. Completed in 1986, this early private sector project sparked the area’s later development as the Seaport District.

Events like the NE Business Conference and BioIT World attracted regional and national visitors, while others, like the Boston Boat Show, drew local crowds. The 1987 DECWorld, Digital Equipment’s user conference, took advantage of the pier’s excellent docking by engaging luxury liners Queen Elizabeth 2 and Oceania to house 2,000 conference attendees onsite. Whenever Boston hosts tall ships from around the world several dock here for visitors to board.

In the 2020s the pier was reimagined once again, creating an engaging 21st century climate-resilient building that enhances waterfront access as never before.

Sign Location

More ...

Resources

- Barrett, Robert E. “The Development of the Port of Boston.” Engineering News, 2 April 1914, pp. 709-717.

- The Commonwealth of Massachusetts. First Annual Report of the Port of Boston Commission. January 1955.

- Commonwealth Pier Five, Massachusetts Cultural Resource Information System Inventory Form. Massachusetts Historical Commission, 2014

- Commonwealth Pier Five, National Register of Historic Places Nomination Form. U.S. Department of Interior, 1979

- Hines, Gerald F. “Boston in War Paint.” The American Review of Reviews: An International Magazine, edited by Albert Shaw, January-June 1918.

- Seasholes, Nancy S. Gaining Ground: A History of Landmaking in Boston. The MIT Press, 2003.

- Stott, Peter. South Boston. Draft industrial archeology report on firms in South Boston. On file at Massachusetts Historical Commission.

- “What is the City Beautiful Movement?” Planetizen. https://www.planetizen.com/definition/city-beautiful last accessed 23 Apr 2023.

- Our gratitude to the Perkins School for the Blind for their partnership in creating the audio files.