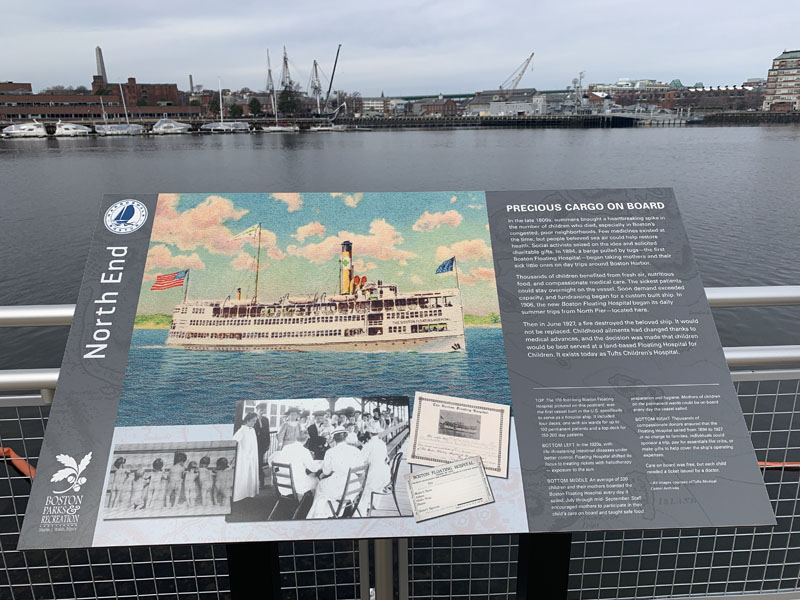

Precious Cargo on Board

in the North End

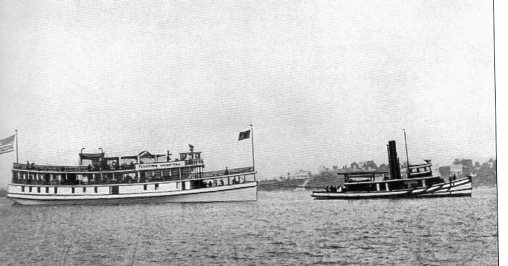

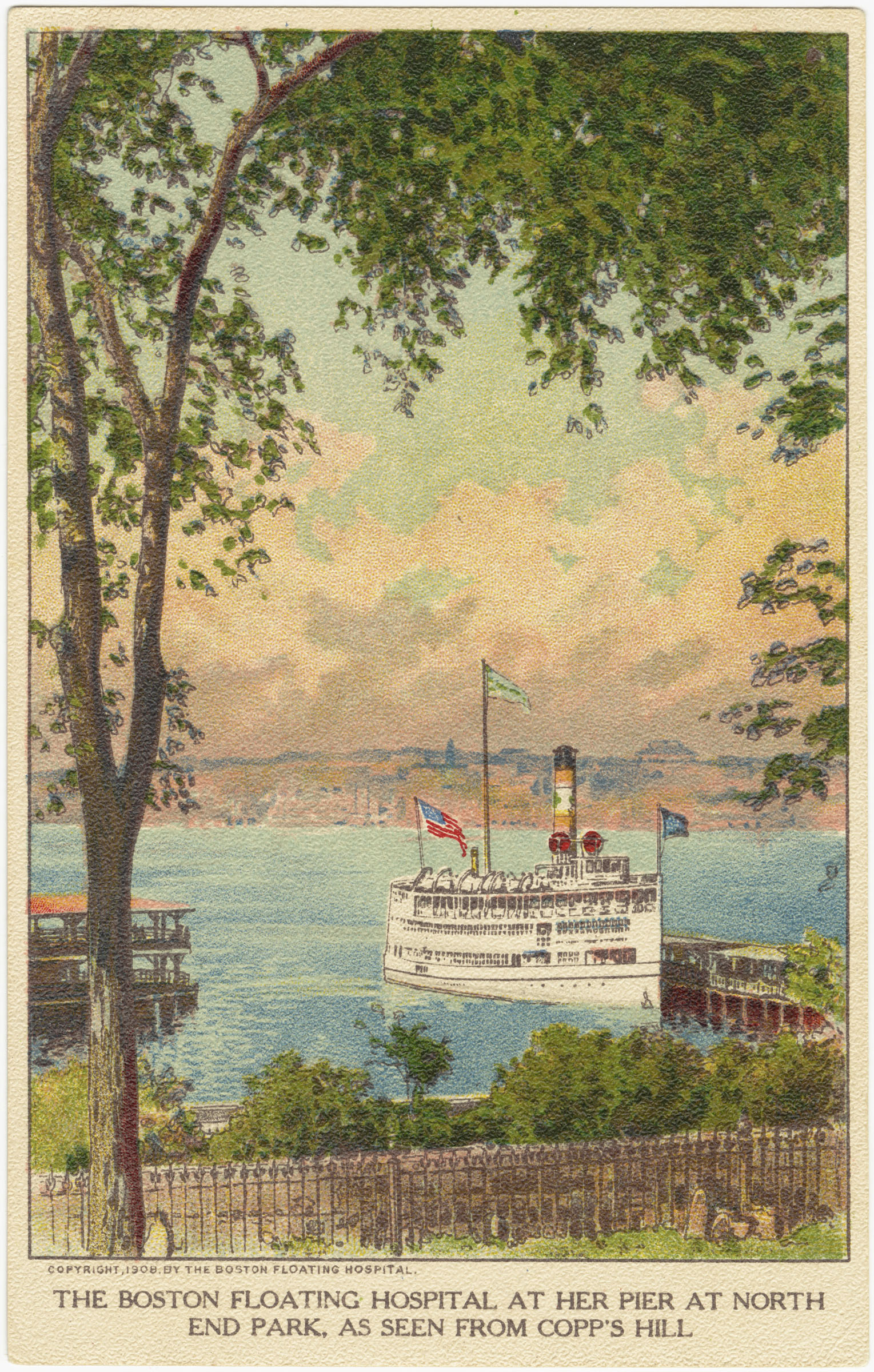

The 170-foot-long Boston Floating Hospital pictured on this postcard, was the first vessel built in the U.S. specifically to serve as a hospital ship. It included four decks, one with six wards for up to 100 permanent patients and a top deck for 150–200 day patients.

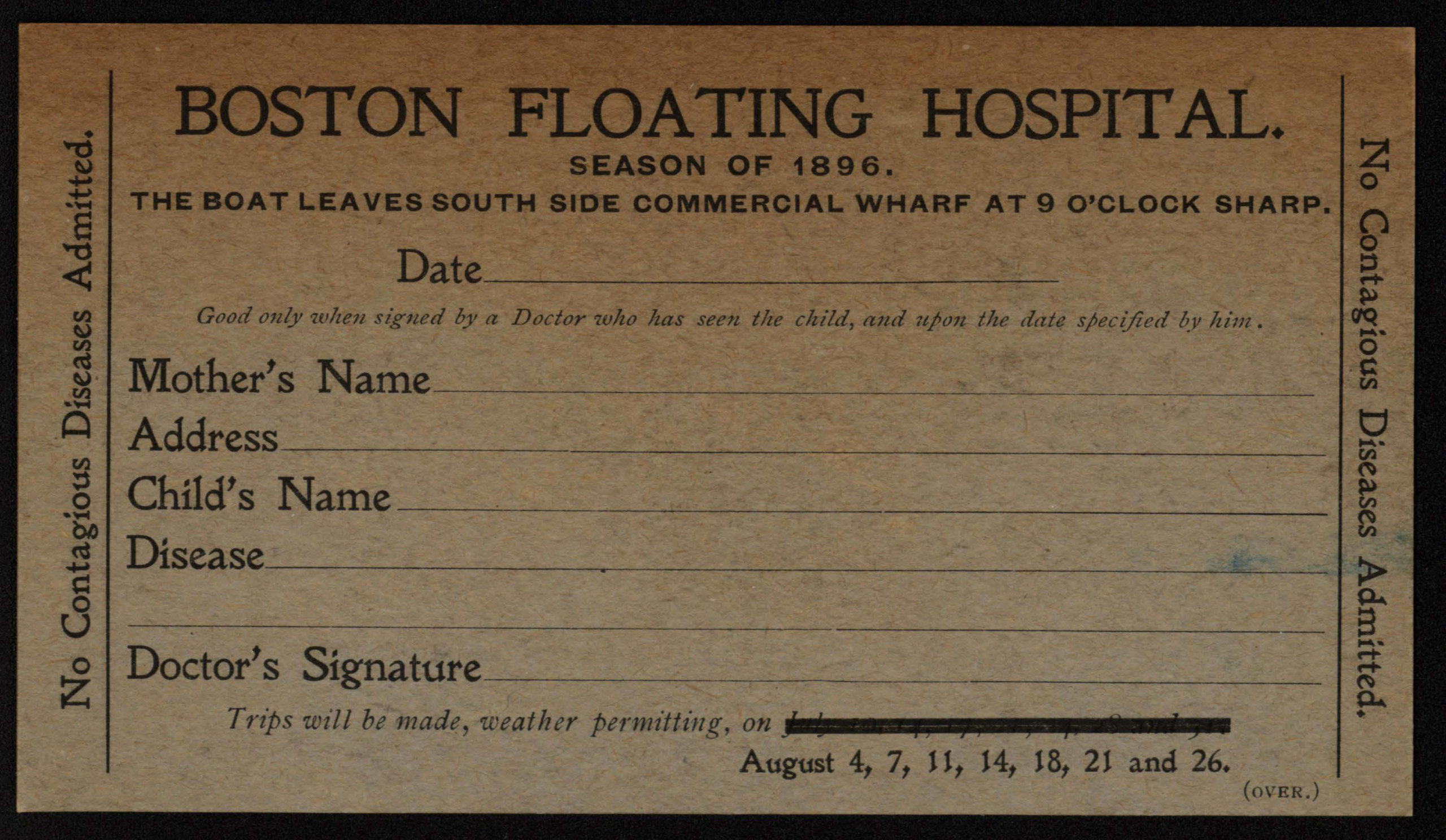

In the late 1800s, summers brought a heartbreaking spike in the number of children who died, especially in Boston’s congested, poor neighborhoods. Few medicines existed at the time, but people believed sea air could help restore health. Social activists seized on the idea and solicited charitable gifts. In 1894, a barge pulled by tugs—the first Boston Floating Hospital—began taking mothers and their sick little ones on day trips around Boston Harbor.

Thousands of children benefited from fresh air, nutritious food, and compassionate medical care. The sickest patients could stay overnight on the vessel. Soon demand exceeded capacity, and fundraising began for a custom built ship. In 1906, the new Boston Floating Hospital began its daily summer trips from North Pier—located here.

Then in June 1927, a fire destroyed the beloved ship. It would not be replaced. Childhood ailments had changed thanks to medical advances, and the decision was made that children would be best served at a land-based Floating Hospital for Children. It exists today as Tufts Children’s Hospital.

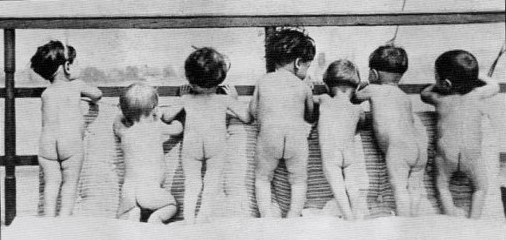

An average of 200 children and their mothers boarded the Boston Floating Hospi-tal every day it sailed, July through mid-September. Staff encouraged mothers to participate in their child’s care on board and taught safe food prepara-tion and hygiene. Mothers of children on the perma-nent wards could be on board every day the vessel sailed.

Courtesy of Tufts Medical Center Archives

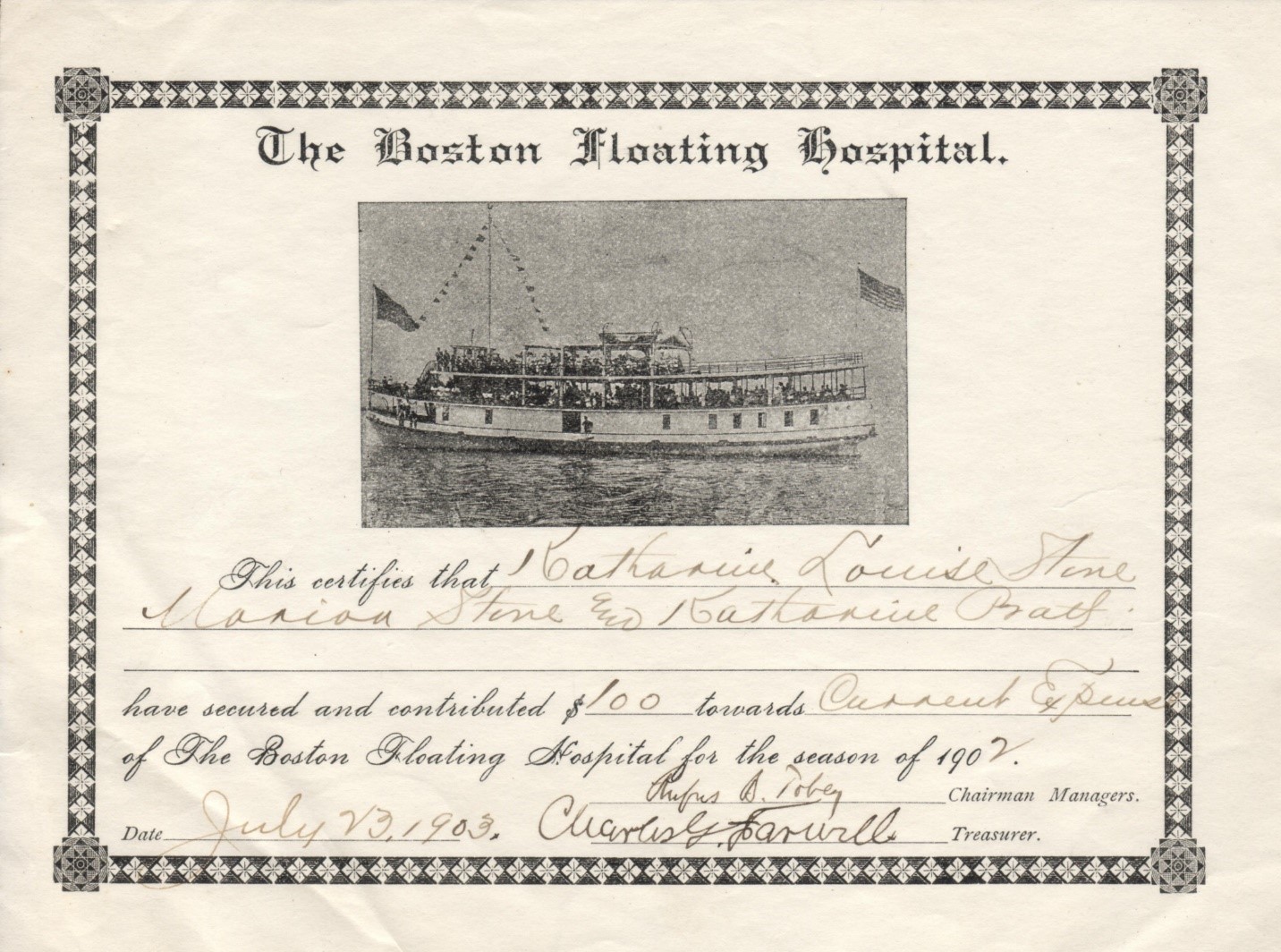

Thousands of compassion-ate donors ensured that the Floating Hospital sailed from 1894 to 1927 at no charge to families. Indivi-duals could sponsor a trip, pay for essentials like cribs, or make gifts to help cover staff salaries and the ship’s operating expenses. Boston’s newspapers often published lists of donors and stories about fund-raising events.

Courtesy of Tufts Medical Center Archives

Sign Location

More …

Resources

- Bloomberg, Robert and Daniel Bird. Tufts Medical Center Images of America. Arcadia Publishing, 2015.

- Prinz, Lucie with Jacoba van Schaik. The Boston Floating Hospital: How a Boston Harbor Barge Changed the Course of Pediatric Medicine. Tufts Medical Center, 2014.

- Multiple articles in the Boston Daily Globe, 1894–1927 including

- “Life for Babes: First Trip of the Floating Hospital Barge,” July 26, 1894.

- “Pictures of Pathos on the Health Ship,” July 24, 1901.

- “Summer Philanthropy in Boston and Plans of the Floating Hospital,” May 19, 1902.

- “Cholera Morbus Antidote. Boston Floating Hospital Designated as One of the Experimental Stations,” May 9, 1903.

- “Launched Amid Tooting and Whistling—Boston Floating Hospital Goes into Water at East Boston While a Mighty Cheer Went up with Spectators,” July 7, 1906.

- “Floating Hospital to Continue Work: Boat Not Needed,” July 2, 1928.

Acknowledgments

- Translation and recording thanks to the generosity of the Boston Marine Society.

- Our gratitude to the Perkins School for the Blind and David W. Cook for their partnership in creating the audio files.

- Warm thanks to Daniel Bird, Tufts Medical Center historian, for his assistance.