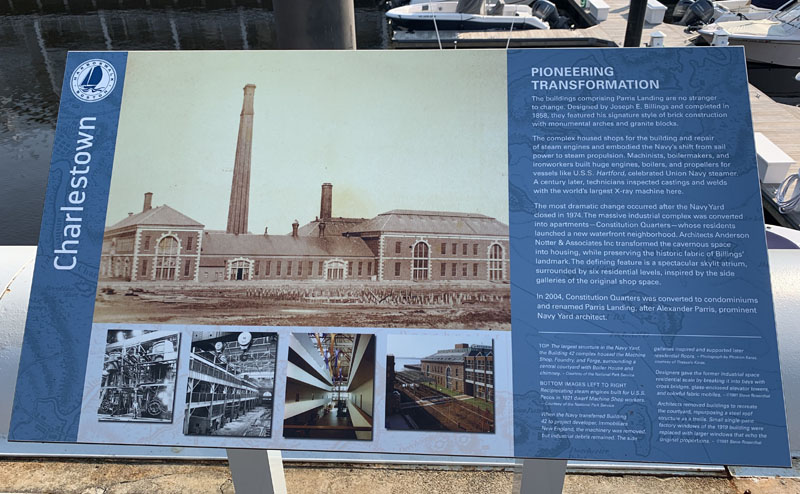

Pioneering Transformation

in Charlestown

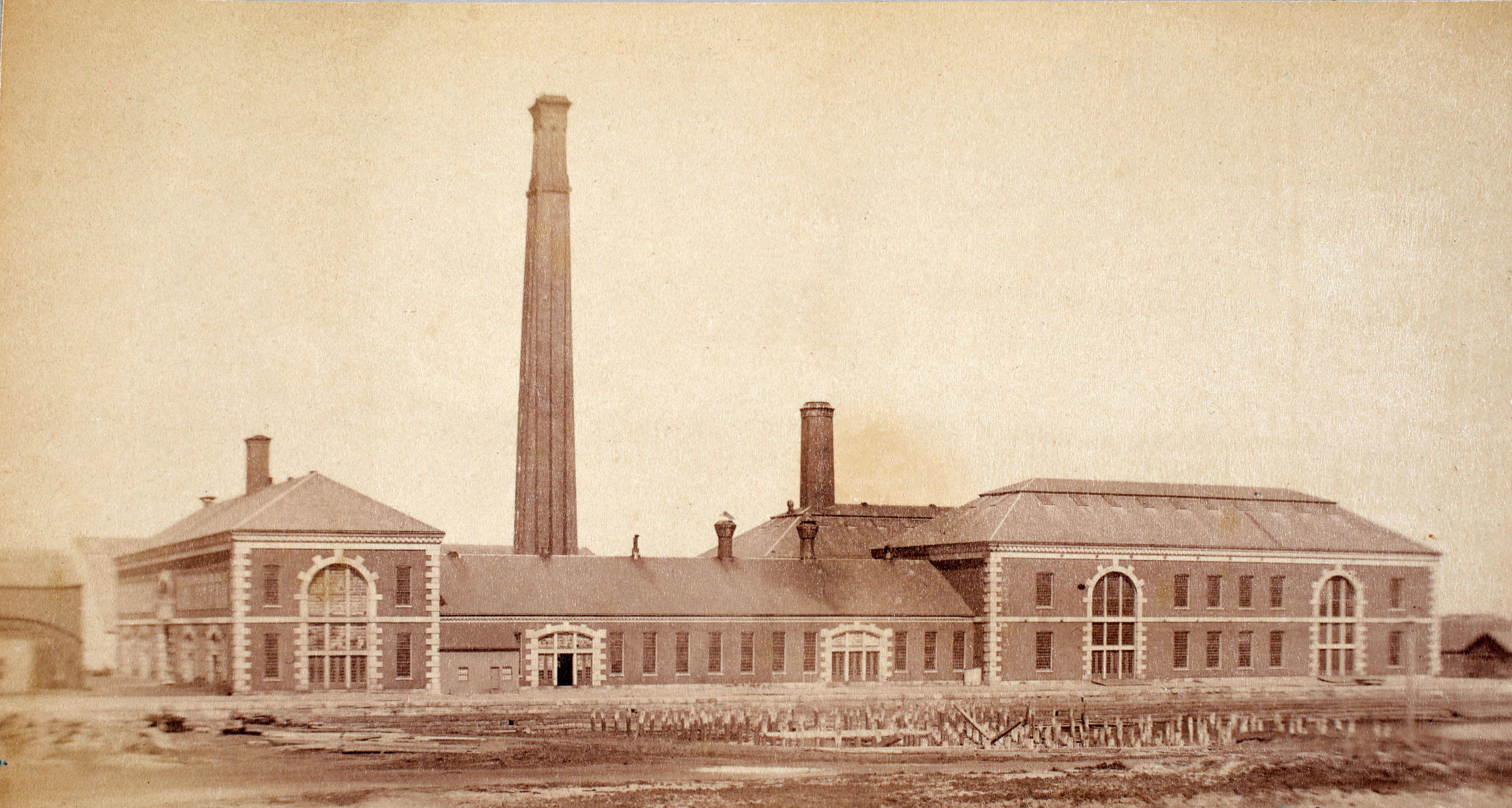

The largest structure in the Navy Yard, the Building 42 complex housed the Machine Shop, Foundry and Forge surrounding a central courtyard with Boiler House and chimney.

Courtesy of the National Park Service

The buildings comprising Parris Landing are no stranger to change. Designed by Joseph E. Billings and constructed in 1858, they featured his signature style of brick construction with monumental arches and granite blocks.

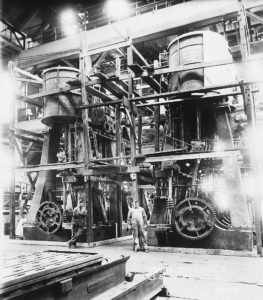

The complex housed shops for the building and repair of steam engines and embodied the Navy’s shift from sail power to steam propulsion. Machinists, boilermakers, and ironworkers built huge engines, boilers, and propellers for vessels like U.S.S. Hartford, the celebrated Union Navy steamer. A century later, technicians inspected castings and welds with the world’s largest X-ray machine.

The most dramatic change occurred after the Navy Yard closed in 1974. The massive industrial complex was converted into apartments—Constitution Quarters–whose residents launched a new waterfront neighborhood. Architects Anderson Notter & Associates Inc., transformed the cavernous space into housing, while preserving the historic fabric of Billings’ landmark. Its defining feature is a spectacular skylit atrium, surrounded by six residential levels, inspired by the side galleries of the original shop space.

In 2004, Constitution Quarters was converted to condominiums and renamed Parris Landing, after Alexander Parris, prominent Navy Yard architect.

Sign Location

More …

Resources

- Alexander, James G. Personal interview. 18 Dec. 2019.

- Anderson Notter Finegold Inc. Award submission, 1982 Homes for Better Living Awards Program.

- Bither, Barbara and Boston National Historic Park. Images of America: Charlestown Navy Yard. Arcardia Publishing, 1999.

- Bearss, Edwin C. and Peter J. Snell. Boston Naval Shipyard National Historic Landmark Study. National Park Service, 1978.

- Black, Frederick R. Charlestown Navy Yard 1890-1973. Cultural Resources Management Study No. 20, Boston Historic Park, 1988.

- Carlson, Stephen P. Charlestown Navy Yard Historic Resource. National Park Service, 2010.

- Charlestown Navy Yard: Boston National Historical Park, Massachusetts. Official National Park Handbook. National Park Service, 1995

- “Grand Award Residential Renovation: Constitution Quarters, Charlestown Navy Yard, Anderson Notter Finegold Inc.” Builder, Oct. 1984.

- Miller, Margo. “Building 42: Charlestown Navy Yard’s lease on residential life.” The Boston Globe, 3 Oct. 1986, pp. 23, 28.

- “Navy Yard Project is poised.” The Boston Herald American, 23 Mar. 1979.

- “A Navy Yard refloated.” Architectural Record, May 1984 pp. 82-87.

- Nilsson, Edwin O. Rehabbing Historic Structures with Energy Conservation: Constitution Quarters, Charlestown Navy Yard. Nilsson + Siden Associates Inc., 1984.

- Stevens, Christopher, et al. Cultural Landscape Report for Charlestown Navy Yard, Boston National Historical Park, Boston, Massachusetts. National Park Service, 2005.

- Temin, Christine. “More art goes public.” The Boston Globe Calendar, 24 Nov 1981, pp. 13-14.

- Yudis, Anthony J. “Italian firm ready if it gets nod as Navy Yard developer.” The Boston Globe, 12 Dec. 1976, p. D1.

- Yudis, Anthony J. “Navy Yard’s new lease on life.” The Boston Globe, 27 Nov. 1977, p. C1.

- Yudis, Anthony J. “Party to celebrate Navy Yard’s recycling.” The Boston Globe, 28 Jan 1979, p. E2.

- Yudis, Anthony J. “Rehab pioneers at Navy Yard.” The Boston Globe, 29 Jun. 1980, pp. E1-E2.

- Yudis, Anthony J. “Navy Yard about ready for tenants.” The Boston Globe, 19 Apr. 1981, p. A55-A56.

- Yudis, Anthony J. “It hasn’t been all smooth sailing for Charlestown’s shipyard project.” The Boston Globe, 24 Jun. 1982, p. 2.

Acknowledgments

Immense gratitude to Jim Alexander and Erica Jackson of Finegold Alexander Architects for all the help they provided – sharing critical insights into the project’s history and design, allowing generous access to the firm’s project materials, and carefully reviewing the final result. Without them this sign would not have been possible.

Our thanks also to the Perkins School for the Blind and David W. Cook for their partnership in creating the audio files.