From Paradise to Prison

in South Boston

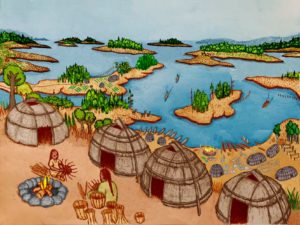

The bountiful tideland environment of the harbor islands provided the Massachusett with fish, shellfish, berries, wood splints for basket-making, fertile soil for farming, and many other resources.

Painting by Robert Peters, a Mashpee Wampanoag artist

Quonehassit, now known as Boston Harbor, is part of the ancestral lands of the Massachusett, one of many Algonkian peoples in eastern North America. For generations, thousands of Massachusett lived on the harbor islands in warmer months, fishing, foraging, and farming. When English captain John Smith visited the Harbor in 1614, he called it “the Paradise of all those parts.”

After founding Boston in 1630, English colonists continued to expand into Native lands. In 1675, indigenous resistance culminated in war between an Algonkian tribal alliance and the English and their Native allies. During the conflict, later called King Philip’s War, colonists rounded up Native people living peacefully among them and forced them into concentration camps on the harbor islands. Without adequate food or shelter, more than half of those imprisoned on the islands died that winter.

Colonists held war captives – men, women, and children – in the fort here on Castle Island before selling them into slavery as far away as North Africa. Hundreds of enslaved Algonkians passed through Castle Island in the 1670s, never to return to their homeland.

“Why shall wee have peace to bee made slaves, & either be kild or sent away to sea to Barbadoes?”

– Algonkian warriors on why they would not surrender during King Philip’s War, as recounted by James Quannapaquait, a Native emissary sent by the English to gather information from “enemy” Algonkians, 1676

Detail of John Smith’s map of New England (first published 1616) showing Quonehassit/Boston Harbor. Although no English settlements existed yet, Smith depicted Native towns with European buildings and asked Crown Prince Charles to give them English names in an effort to claim the land as an English colony.

Courtesy of the Norman B. Leventhal Map & Education Center at Boston Public Library

“We are still here. Against all odds, we have survived as a people. Ritual dance, drum, rattle, song, and rites of passage all enable the present day Massachusett tribe to transfer knowledge of our ancestors to succeeding generations. We thank our ancestors for keeping the traditions, for their fore-sight and the gifts they left us.”

– Ren Green, Medicine Sac’hem of the Massachusett, 2018

Sign Location

More …

Resources

- Brooks, Lisa Tanya. “Our Beloved Kin: A New History of King Philip’s War.” New Haven, Yale University Press, 2018

- Fisher, Linford D. “‘Why shall wee have peace to bee made slaves’: Indian Surrenderers during and after King Philip’s War.” Ethnohistory 64:1, January 2017.

- Hilleary, Cecily. “In Northernmost Bermuda, Islanders Celebrate Native American Connection.” VOA News. February 6, 2021. https://www.voanews.com/a/usa_northernmost-bermuda-islanders-celebrate-native-american-connection/6201548.html

- Lepore, Jill. “The Name of War: King Philip’s War and the Origins of American Identity.” New York, Knopf, 1998.

- Mandell, Daniel R. “King Philip’s War: Colonial Expansion, Native Resistance, and the End of Indian Sovereignty.” Baltimore, Johns Hopkins University Press, 2010

- Nemasket Nation website

- Peterson, Mark. “The City-State of Boston: The Rise and Fall of an Atlantic Power, 1630-1865.” Princeton, Princeton University Press, 2019

- Smith, John, “A Description of New England” (1616). Zea E-Books in American Studies. 3.

https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/zeaamericanstudies/3 - “Examination and Relation of James Quannapaquait, Alias James Runnymarsh” (1676.) Yale Indian Papers Project. http://hdl.handle.net/10079/digcoll/1018319

- Young, Lance. “From Paradise to Prison.” Partnership of Historic Bostons. https://historicbostons.org/blog-1/deer

Acknowledgments

-

The title of this sign, “From Paradise to Prison” is borrowed from an essay by Lance Young, chief sachem of the Nemasket Nation, Wolf Clan, and chairman of the Nemakset Tribal Council. The full essay provides a more complete account of the imprisonment of Native people on the harbor islands during King Philip’s War and can be found here: https://historicbostons.org/blog-1/deer

-

This sign was developed in consultation with the Massachusett Tribal Council (https://massachusetttribe.org). Thank you!

- All the interpretive panels at Castle Island and Pleasure Bay are made possible thanks to a Boston Community Preservation Fund grant.

- Warm thanks to Brendan Albert and Kate Gutierrez for generously funding Spanish translations for the Castle Island/Pleasure Bay signs.

- Our gratitude to the Perkins School for the Blind Recording Studio and Thomasine Berg for their partnership in creating the audio files.