First Street: The Original Shoreline

in South Boston

Detail from 1806 map by Caleb Parry Wayne captures Dorchester Neck (population: 60) and the flats to its north shortly after the area was annexed by Boston and renamed South Boston. The star indicates where you are now.

Courtesy of the Norman B. Leventhal Map & Education Center at Boston Public Library

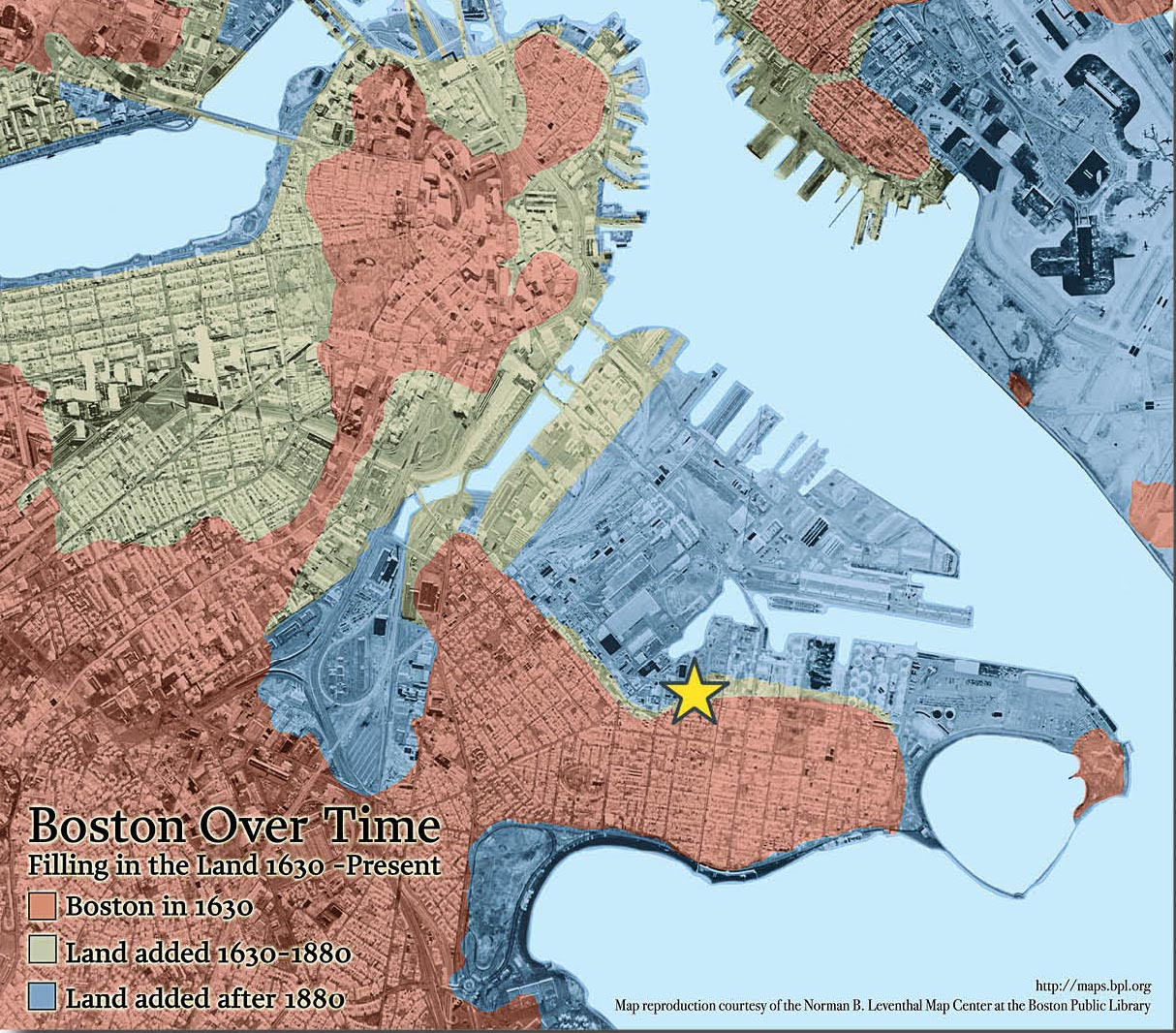

In 1804, Boston annexed the thinly populated peninsula known as Dorchester Neck and renamed it South Boston. This spot was on the South Boston Flats: a vast expanse of salt marsh laced with inlets. The land to the north and northwest of here today—the Fort Point Channel and Seaport neighborhoods—as well as the Reserved Channel are all man-made.

By 1845, South Boston’s population had grown to 10,020. First Street and a section of Second Street ran along the original shoreline. Glassmakers, shipbuilders, and ironworkers established businesses along the waterfront, built wharves, and began to fill the flats as far as 1,650 feet from the shoreline, as the law permitted. Bay State Iron Company created the land in front of you, using a long-standing Boston technique. They enclosed an area of shallow water with a sea wall and then deposited fill on the inland side. That sea wall is still visible along the Reserved Channel.

In the decades that followed, landmaking expanded South Boston from its original 580 acres to about 1,600 acres. The once rural peninsula was completely transformed.

This detail from B. F. Nutting’s 1866 bird’s eye view, shows multiple landmaking projects north of First Street in South Boston. In the foreground, note the huge wharf begun by Boston Wharf Company in the 1830s. It formed the east side of today’s Fort Point Channel. In 1855, the Boston & New York Central Railroad built the almost mile-long pile rail bridge to its depot near present day South Station. Today, South Boston Bypass Road crosses South Boston where the tracks once ran.

Courtesy of the Norman B. Leventhal Map & Education Center at Boston Public Library

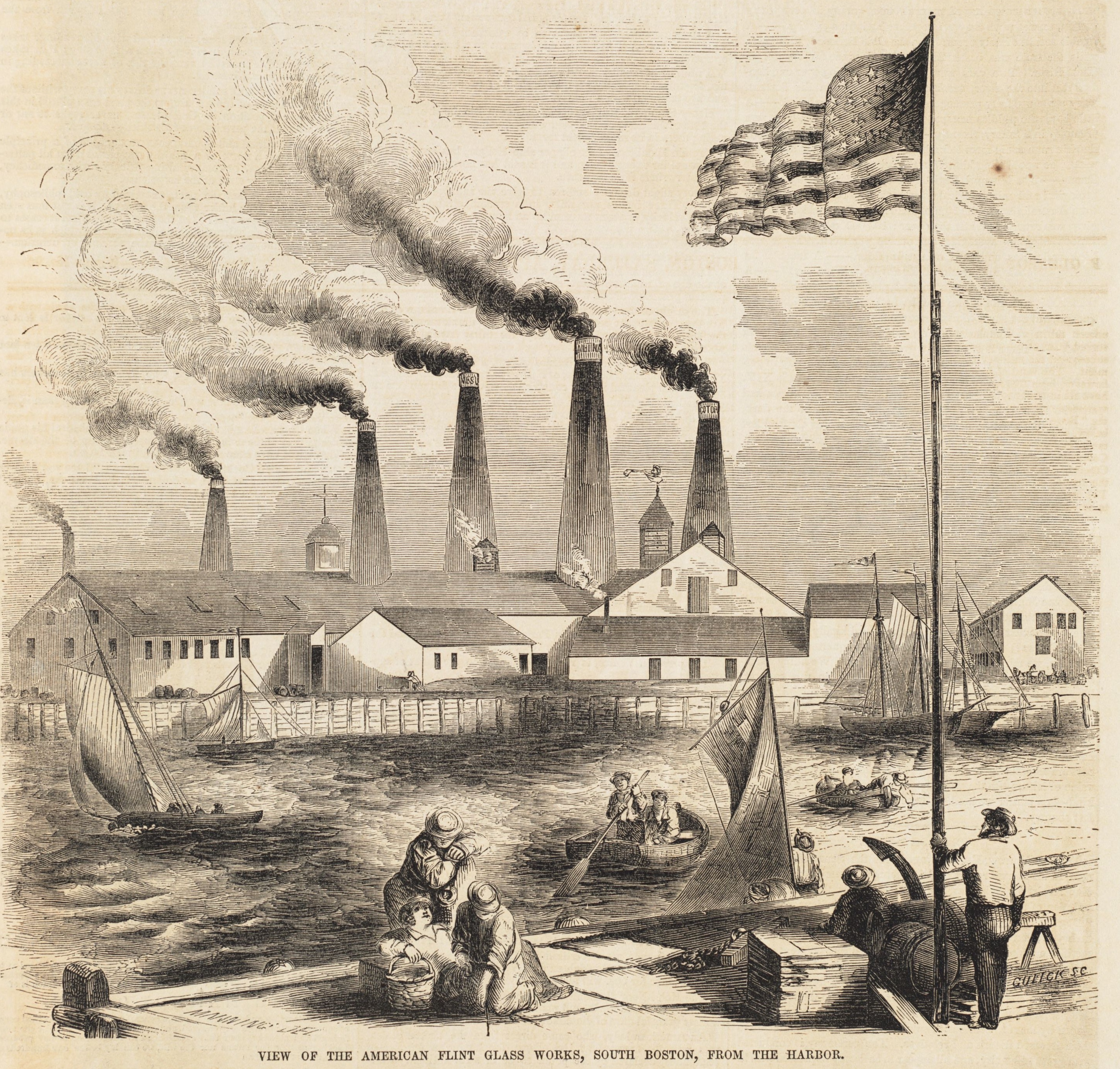

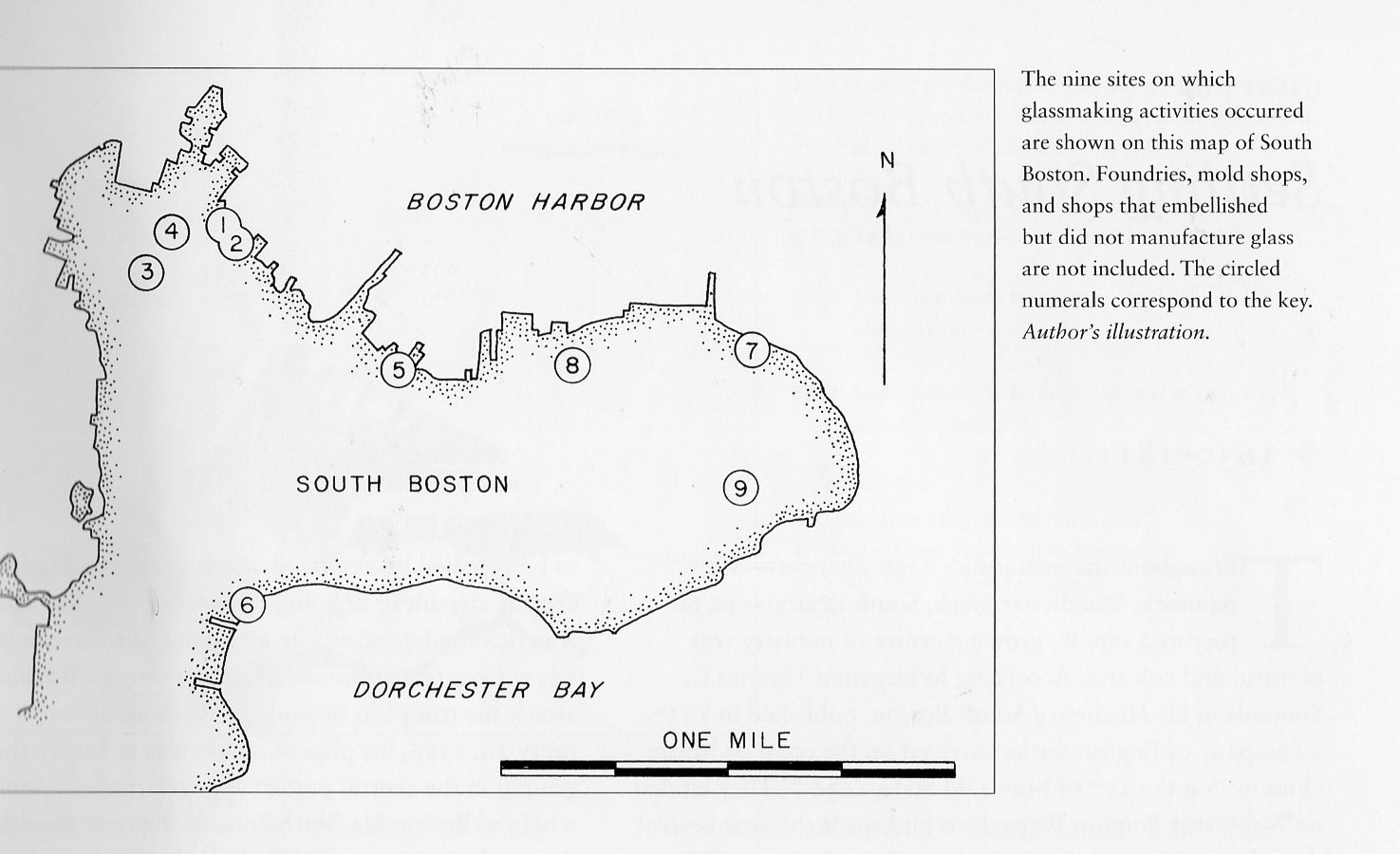

A short distance to the east and west of here two glassmaking factories were among several that built on, or very close to, South Boston’s original waterfront. American Flint Glass Works, pictured here, stood on East First Street. Archaeologists uncovered the factory’s footprint in 1997.

Engraving by David B. Gulick printed in April 1853 Gleason’s Pictorial Drawing-Room Companion, Courtesy of Boston Public Library

Sign Location

More …

Resources

- Kaiser, Joan E. The Glass Industry in South Boston. University Press of New England, 2009.

- Seasholes, Nancy S. Gaining Ground: A History of Landmaking in Boston. The MIT Press, 2003.

- Toomey, John & Edward Rankin. History of South Boston (Its Past and Present) and Prospects for the Future. Published in Boston by the authors, 1901.

Acknowledgments

- Deep thanks to Nancy Seasholes for sharing her expertise and for all her support.

- Our gratitude to the Perkins School for the Blind and David W. Cook for their partnership in creating the audio files.