Creating Pleasure Bay

in South Boston

This 1925 aerial photo shows where soil dredged from both the Reserved Channel and Pleasure Bay was being dumped to make new land between Castle Island and South Boston. That land is now MassPort’s Conley Container Terminal. On the right, the now-demolished Head House can be seen flanked by beaches at City Point.

Courtesy of Boston Public Library

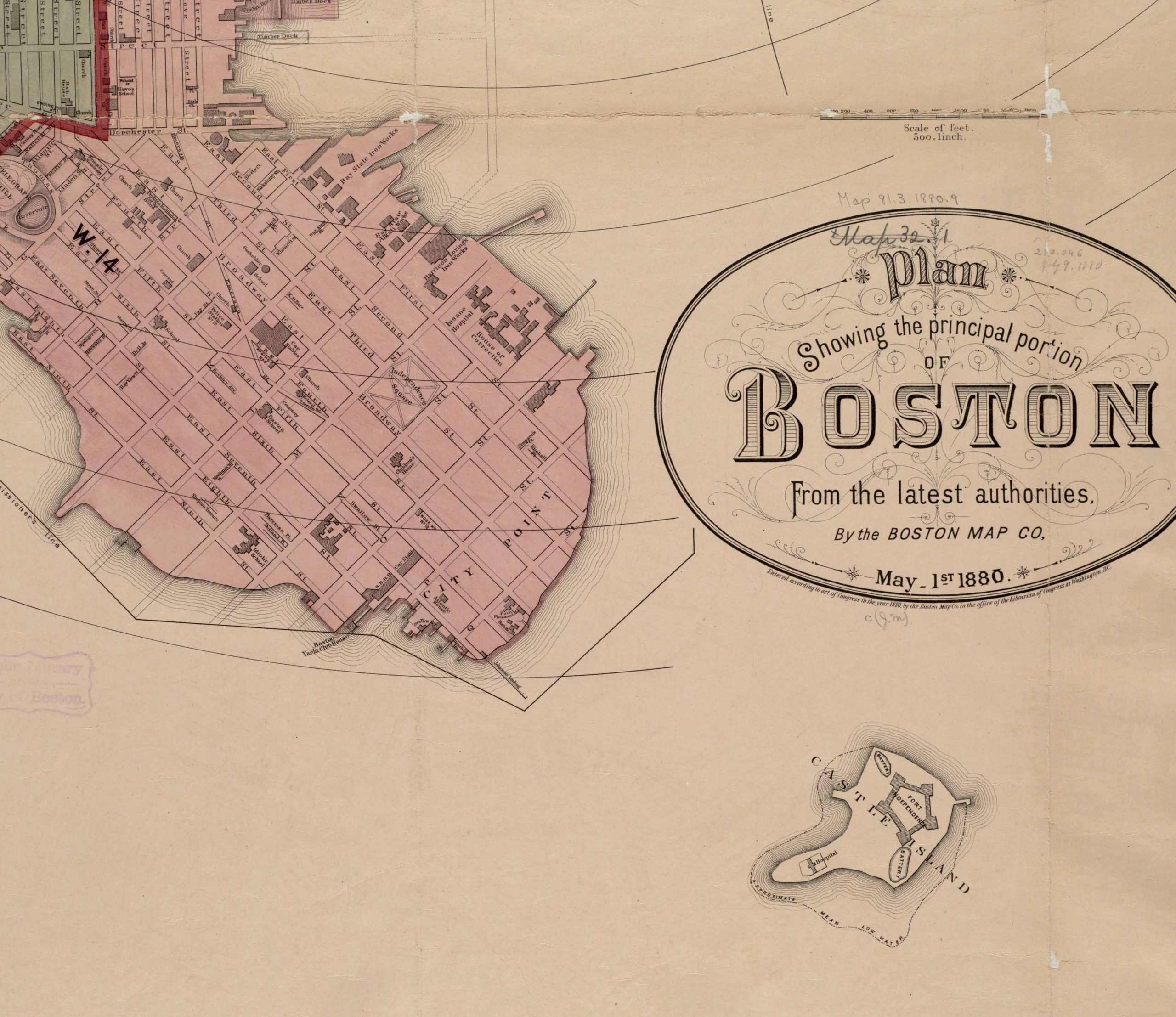

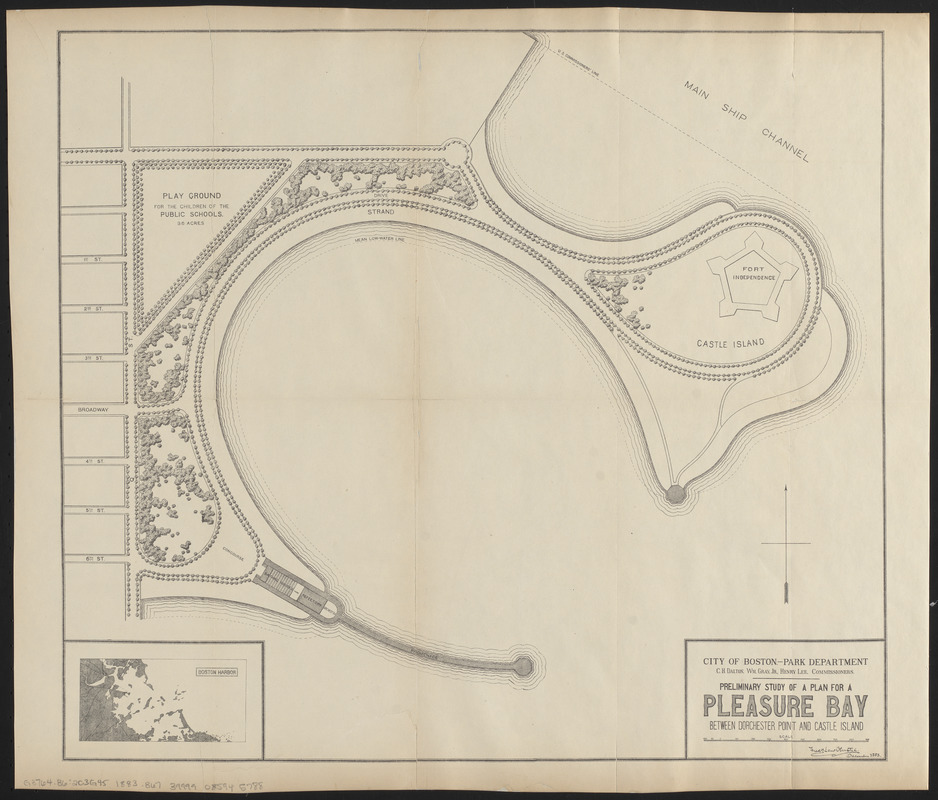

When landscape architect Frederick Law Olmsted drafted his 1883 plan for South Boston’s Marine Park, he envisioned connecting it to Castle Island by filling in some 600 acres of mudflats. That took nearly 50 years to achieve.

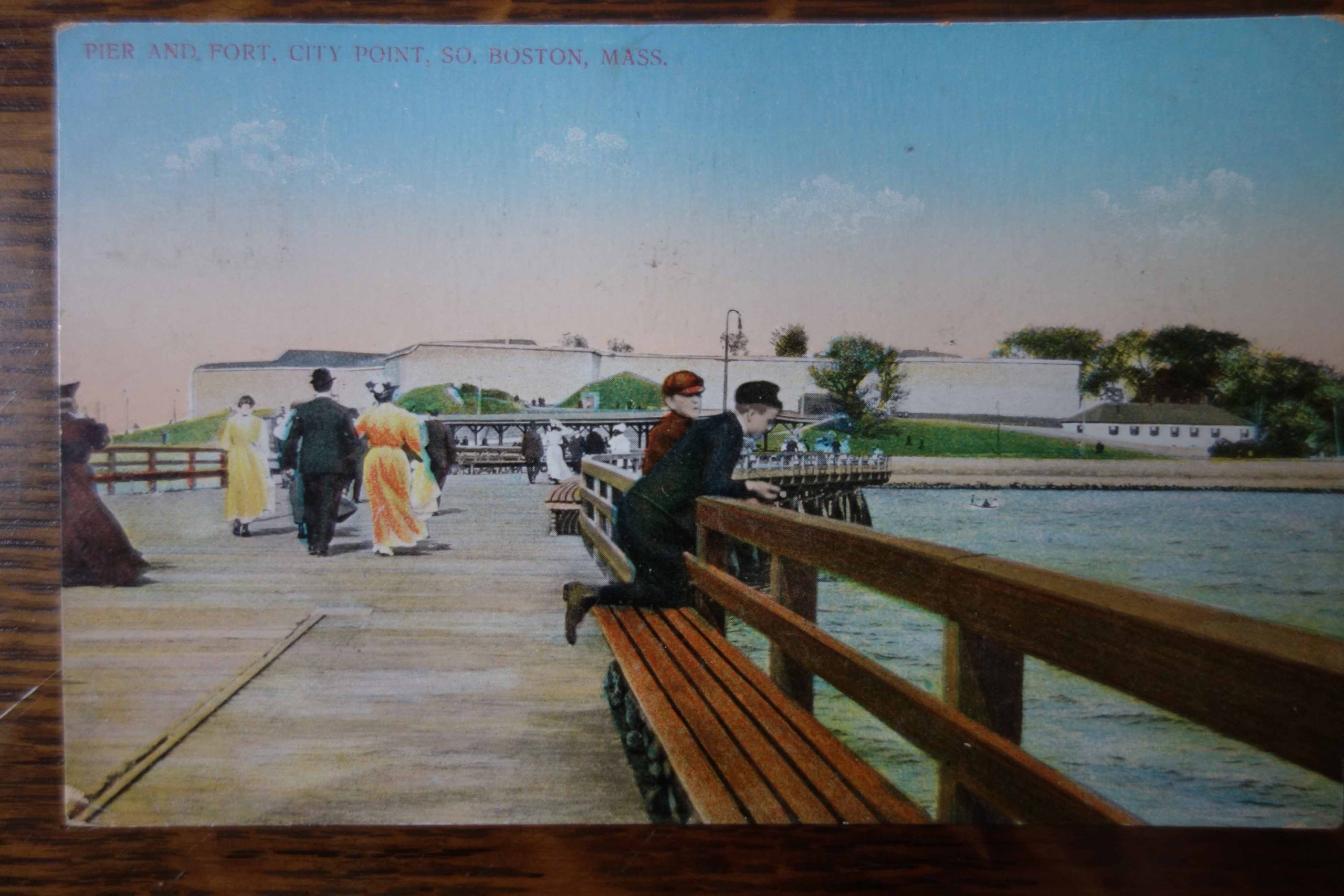

First a wooden footbridge was built in 1892, and a delighted public flocked to the island. On Thursday nights in the summer, dances were held there under a wooden canopy hung with colored lanterns. The footbridge was replaced by a cement path across the newly made land in 1928, and then by a paved road in 1932.

Across from Castle Island an iron pier stretched seaward from the Head House. It defined Pleasure Bay and fulfilled Olmsted’s plan of increasing public access to the health benefits of sea air. The 1938 hurricane heavily damaged the pier; it was replaced in 1953 by a granite causeway. Six years later, Pleasure Bay was enclosed by a dike with two openings that allow the tide to flow in and out.

Sign Location

More …

Resources

-

O’Connor, Thomas H., South Boston My Home Town (second edition), Northeastern University Press, 1988, 1994.

- Reid, William J. Castle Island and Fort Independence. Trustees of the Public Library of the City of Boston, 1995.

-

Sullivan, Jim, South Boston, Postcard History Series, Arcadia Publishing, 2007.

-

Seasholes, Nancy S., Gaining Ground, A History of Landmaking in Boston, MIT Press, 2003.

Acknowledgments

- This sign is made possible by funding from a Boston Community Preservation Act grant.

- Warm thanks to historians at the Castle Island Association for their guidance and expertise in creating this sign and to the Department of Conservation and Recreation for their partnership.

- Thank you to Brendan Albert and Kate Gutierrez for generously funding Spanish translations for the Castle Island/Pleasure Bay signs.

- Our gratitude to the Perkins School for the Blind Recording Studio and Thomasine Berg for their partnership in creating the audio files.