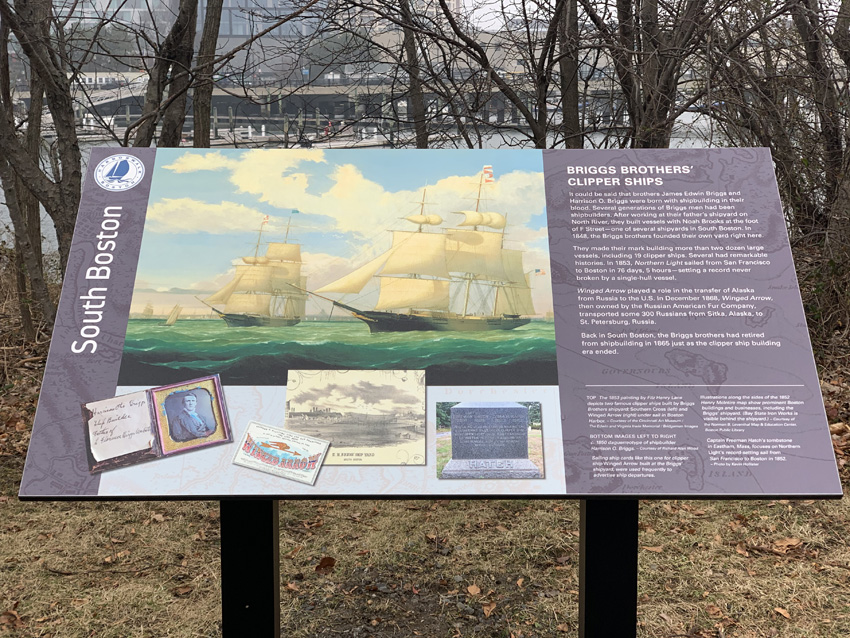

Briggs Brothers’ Clipper Ships

in South Boston

The 1853 painting by Fitz Henry Lane depicts two famous clipper ships built by Briggs Brothers shipyard: Southern Cross (left) and Winged Arrow (right) under sail in Boston Harbor.

Courtesy of the Cincinnati Art Museum/The Edwin and Virginia Irwin Memorial/Bridgeman Images

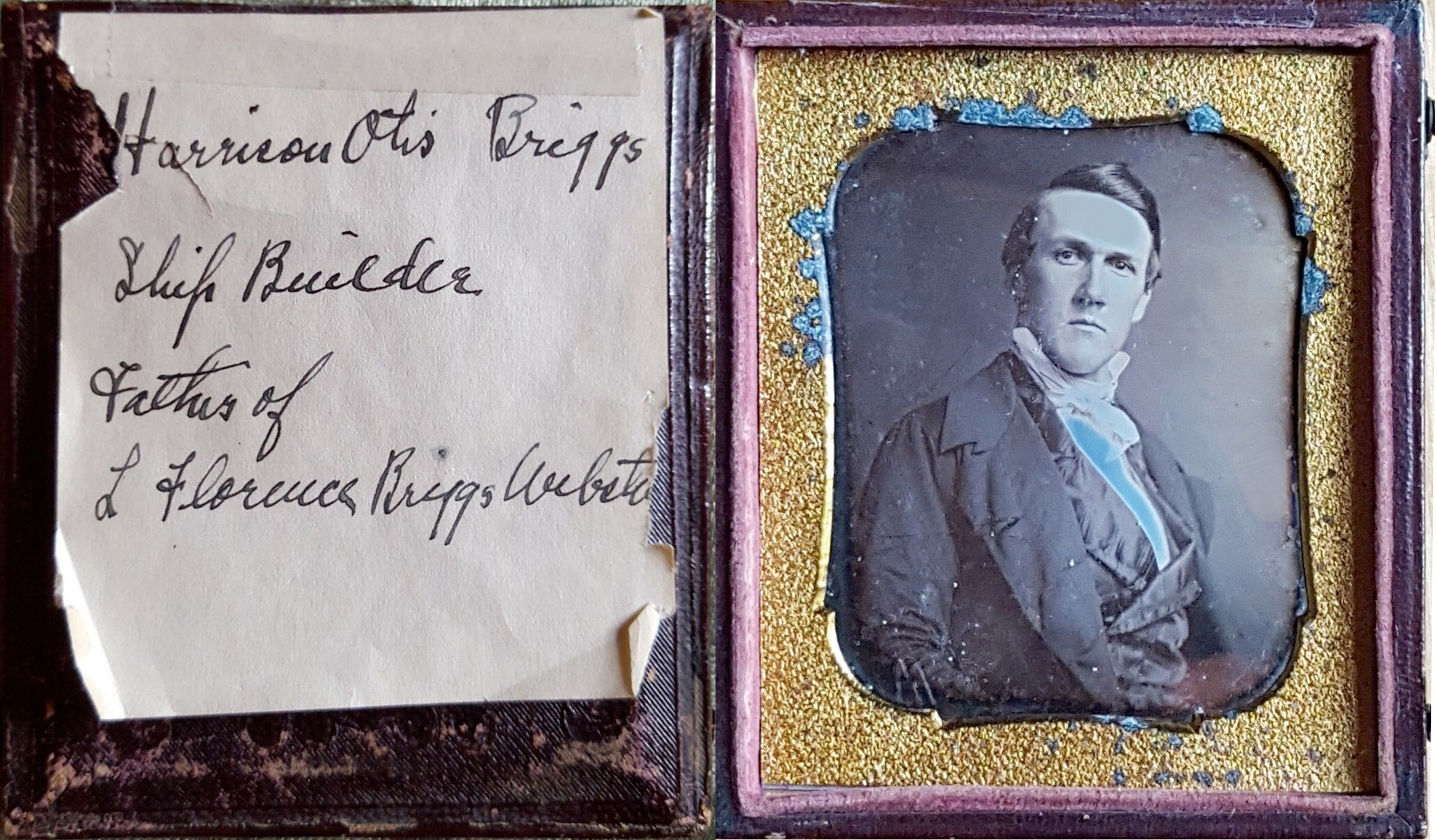

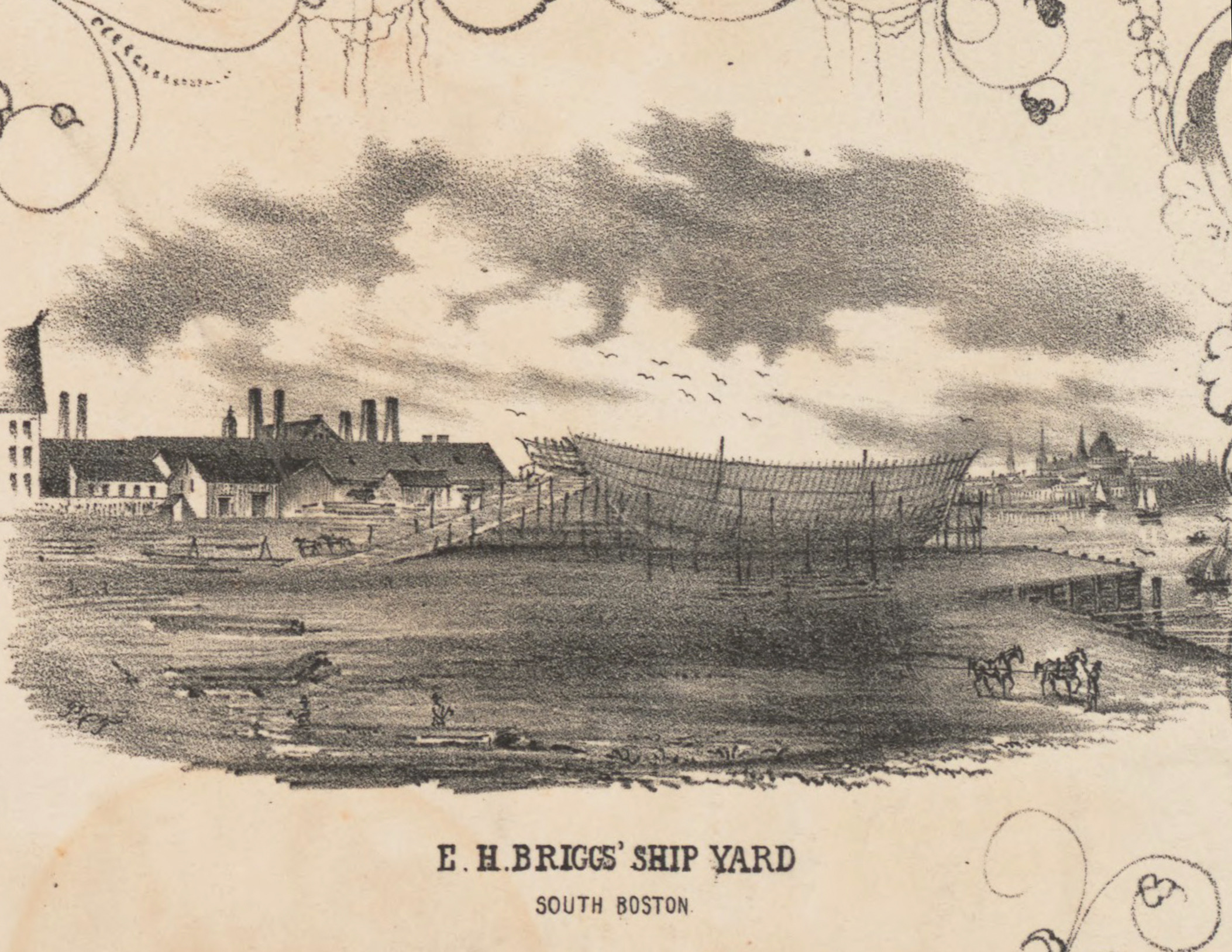

It could be said that brothers James Edwin Briggs and Harrison O. Briggs were born with shipbuilding in their blood. Several generations of Briggs men had been shipbuilders. After working at their father’s shipyard on North River, they built vessels with Noah Brooks at the foot of F Street—one of several shipyards in South Boston. In 1848, the Briggs brothers founded their own yard right here.

They made their mark building more than two dozen large vessels, including 19 clipper ships. Several had remarkable histories. In 1853, Northern Light sailed from San Francisco to Boston in 76 days, 5 hours—setting a record never broken by a single-hull vessel.

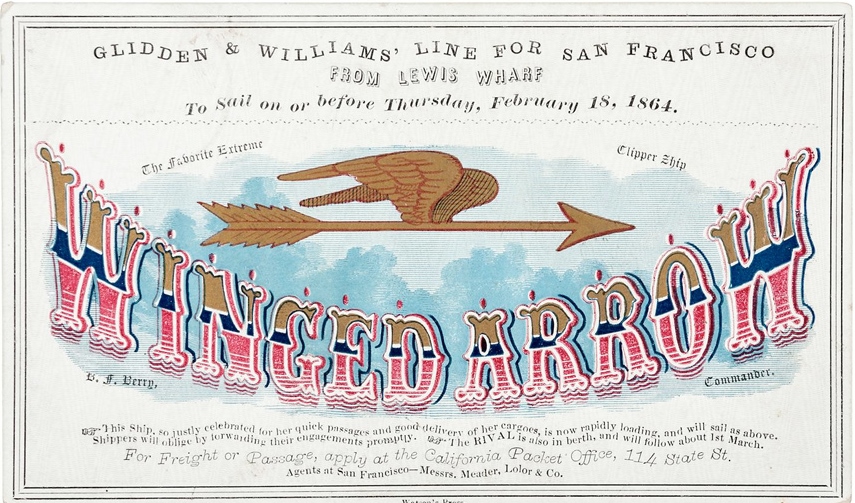

Winged Arrow played a role in the transfer of Alaska from Russia to the U.S. In December 1868, Winged Arrow, then owned by the Russian American Fur Company, transported some 300 Russians from Sitka, Alaska, to St. Petersburg, Russia.

Back in South Boston, the Briggs brothers had retired from shipbuilding in 1865 just as the clipper ship building era ended.

Sign Location

More …

Resources

- Andrews, Clarence Leroy. The Story of Sitka: The Historic Outpost of the Northwest Coast, the Chief Factory of the Russian American Company. Press of Lowman & Henford, 1922.

- “The Astonishing Voyage of the Northern Light” New England Historical Society, based on Shipmasters of Cape Cod by Henry Kittredge.

- Clark, Arthur Hamilton. The Clipper Ship Era: An Epitome of Famous American and British Clipper Ships, their owners, builders, commanders, and crews 1843-1869. G. P. Putman’s Sons, 1910.

- Howe, Octavius T. & Frederick C. Matthews. American Clipper Ships, 1833-1858. Dover Publications, Inc. 1926.

- Toomey, John & Edward Rankin. History of South Boston (Its Past and Present) and Prospects for the Future. Published in Boston by the authors, 1901.

- Description of the Winged Arrow in Boston Daily Atlas, August 2, 1852.https://www.maritimeheritage.org/ships/Clippers_T-to-Z.html#Winged-Arrow

- about sailing cards

Acknowledgments

- Thank you to Richard Wood who first alerted us to the Briggs Brothers Shipyard in South Boston.

- Our gratitude to the Perkins School for the Blind and David W. Cook for their partnership in creating the audio files.