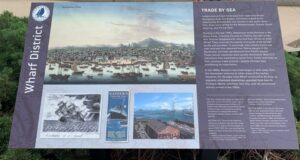

Trade by Sea

in the Wharf District

Ship owners with offices on India Wharf were very active in the China Trade. Like all foreigners doing business in China, U.S. traders were restricted, during the six-month trading season, to living and completing transactions in a designated area of Quangzhou (Canton) shown on this circa 1800 painting.

Independence freed Americans from restrictive British Navigation Acts, and Boston merchants leaped at the opportunity to trade with any country in the world. Soon their ships were sailing for the Mediterranean, Russia, South America, and the Far East.

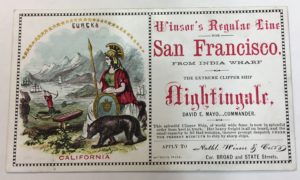

Starting in the late 1700s, Bostonians made fortunes in the China Trade, including Thomas H. Perkins, George Lyman, and Thomas Wigglesworth, who had their offices on India Wharf. They imported thousands of pounds of tea as well as silk and porcelain. In exchange, they initially traded sea otter and seal furs obtained from Native people in the Northwest, and later sandalwood from Pacific islands. These natural resources were quickly decimated. Most U.S. merchants then switched to opium from Turkey and India as their principal trade product—despite Chinese laws prohibiting its importation.

In the 1860s, Boston’s sea trade began to shift away from the downtown wharves to other areas of the harbor. However, for decades India Wharf continued to be busy as regularly scheduled steamships operated from here to Portland, Maine, and New York City, until all commercial activity ended in the 1950s.

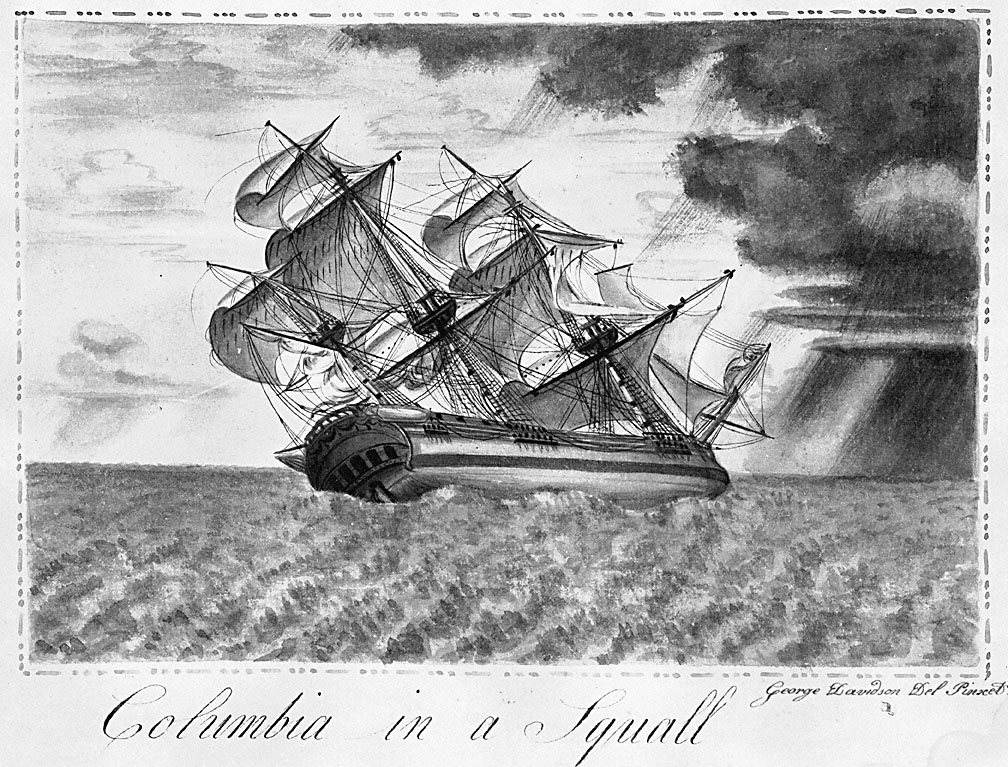

The Columbia-Rediviva, sailing out of Boston, was the first vessel bearing a U.S. flag to circumnavigate the world (1787-1790). Her crew launched the early U.S. trade of sea otter fur for Chinese products.

Illustration by George Davidson, a crew member on Columbia-Rediviva’s second fur-trading voyage in 1793. Courtesy of the Oregon Historical Society

In the second half of the 19th century, steamship sheds were built along the edge of India Wharf for easy loading. The Metropolitan Steamship Company (founded in 1866) and Portland Steam Packet Company operated from India Wharf until they were consolidated in the early 1900s into what became the Eastern Steamship Lines.

Original 1906 photo from Library of Congress; colored image courtesy of TD Bank

Sign Location

More …

Resources

- Adams Jr., Russell B. The Boston Money Tree. Thomas Y. Crowell Co., 1977.

- Bunting, W. H. Portrait of a Port, Boston 1852-1914. The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 1971.

- Bunting, W. H. The Camera’s Coast: Historic Images of Ship and Shore of New England. Historic New England, 2006.

- Dolin, Eric Jay. When America First Met China: An Exotic History of Tea, Drugs, and Money in the Age of Sail. Liveright Publishing Corp., 2012.

- Hawes, Dorothy Schurman. To the Farthest Gulf: The Story of the American China Trade. Reprinted by The Ipswich Press, 1990 from articles in the “Essex Institute Historical Collections,” 1841.

- Layton, Thomas N. The Voyage of the Frolic: New England Merchants and the Opium Trade. Stanford University Press, 1997.

- “Other Merchants and Sea Captains of Old Boston,” State Street Trust, 1919. (p47 for Perkins info)

- Col Frank Forbes: “The Old Wharves of Boston” Proceedings of the Bostonian Society, Jan 15, 1952.

- Rossiter, William Sidney, Ed. Day and Ways in Old Boston. “The Old Boston Water Front,” Frank H. Forbes, R. H. Stearns & Co., 1915.

- Spence, Jonathan D. The Search for Modern China. W.W. Norton & Co., 1990.

- Vrabel, Jim. When in Boston: A Timeline and Almanac. Northeastern University Press, 2004.

- Whitehill, Walter Muir. Boston: A Topograhical History. Belknap Press, Harvard University Press, 2nd Ed 1968.

- For more about key U.S. companies involved in the early China trade www.Industrialhistoryhk.org

- For information about a replica of the Columbia Rediviva https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sailing_Ship_Columbiahttp://www.lewis-clark.org/article/577#rediviva