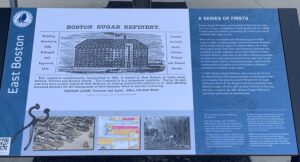

A Series of Firsts

in East Boston

Advertisement from 1852 Boston City Directory.

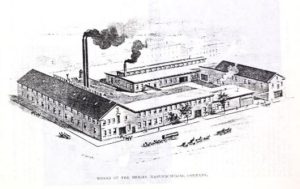

Boston Sugar Refinery, once located along Lewis Street between Webster and Sumner Streets, was the first industry established in East Boston. By the 1850s, it employed 200 people, processing 25 million pounds of imported raw sugar a year.

This refinery is credited with developing granulated sugar in 1853, to replace sugar cones and loaves. Workers raked moist refined sugar on a steam table until it was thoroughly dried. Then they used sieves to separate the crystals by grade. Eighteen years later, Charles Hersey of South Boston improved on the labor-intensive process; he patented a granulating machine that was soon a part of every sugar refinery. Granulated sugar made precise measurements possible and contributed to Boston’s success as a leading candy maker.

In 1887, Boston Sugar Refinery was among the first to be absorbed by what became known as the Sugar Trust—a monopoly that grew to control 98 percent of sugar refining in the U.S. The Sugar Trust first combined East Boston’s sugar refinery with another refinery in the city, and then closed it. By 1901, Boston Sugar Refinery’s buildings were used as warehouses.

This detail from O. H. Bailey’s 1879 bird’s-eye view of East Boston shows the Boston Sugar Refinery buildings—indicated with a number 12—as they appeared at that time, stretching all the way from the corner of Sumner and Lewis streets to the waterfront.

Courtesy of the Norman B. Leventhal Map & Education Center at Boston Public Library

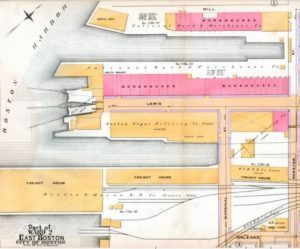

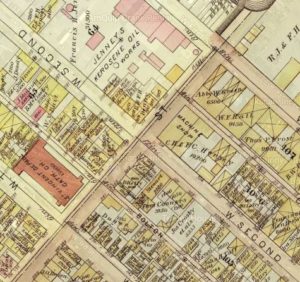

By 1892, the date of this Bromley insurance map, Boston Sugar Refinery had been absorbed by the American Sugar-Refining Company, also known as the Sugar Trust. Their name appears on the buildings, with the Boston refinery as lessee.

Atlas of the City of Boston, East Boston by G. W. Bromley & Co., Courtesy of the Norman B. Leventhal Map & Education Center at Boston Public Library

Sign Location

More …

Resources

- Butler, Allison E. “A Sweet Beginning: The U.S. Sugar Monopoly,” Origins. Published by History Departments of the Ohio State University and Miami University, January 2019.

- 1897 Congressional Record Containing the Proceedings and Debates of the Fifty-Fifth Congress, First Session; also Special Session of the Senate, Volume XXX, Government Printing Office, 1897.

- Dana, Richard Henry, Jr. To Cuba and Back: A Vacation Voyage. Ticknor & Fields, Boston, 1859.

- Depew, Chauncey M. ed. 1795-1895 One Hundred Years of American Commerce: A History of American Commerce by One Hundred Americans. “American Sugar,” by John E. Searles. D. O. Haynes & Company, 1895.

- Graney, Mimi. Fluff: The Sticky Sweet Story of An American Icon. Union Park Press, 2017.

- Fisher’s National Magazine & Industrial Record, Vol III. Edited and Published by Redwood Fisher, New York, 1846.

- Historic & Archaeological Resources of the Boston Area: A Framework for Preservation Decisions. Massachusetts Historical Commission, 1982, reprinted 1991.

- Mescher, Virginia. “How Sweet it is: A History of Sugar and Sugar Refining in the United States.”

- The National Cyclopedia of American Biography, Being the History of the United States (Vol 17), published by James T. White & Co., 1920.

- “The Planters’ Monthly, Vol 1,” published by Planters’ Labor & Supply Co., Honolulu. Oct 1882.

- Rolph, George Morrison. Something About Sugar, Its History, Growth, Manufacture and Distribution. John J. Newbegin Publisher, 1917.

- Seasholes, Nancy & The Cecil Group. Sites for Historical Interpretation on East Boston’s Waterfronts. Boston Redevelopment Authority, 2009.

- A Sketch of the Recent Improvements at East-Boston, Printed by J. T. Buckingham, Boston, 1836.

- Sumner, William H. History of East Boston: With Biographical Sketches of its Early Proprietors, and an Appendix. Boston: William H. Piper and Company, 1858.

- Vogt, Paul. The Sugar Refining Industry in the United States. University of Pennsylvania, 1908.

- Ward, Artemas. The Grocer’s Hand-Book and Directory. Philadelphia Grocer Publishing Co. 1883.

- Zerbe, Richard. “The American Sugar Refining Company 1887-1914: The Story of a Monopoly,” The Journal of Law and Economics, Volume 12, No. 2, October 1969.

- About sugar cones and nips

- Excellent overview of history of sugar, “How Sweet it is: A History of Sugar and Sugar Refining in the United States,”

- For commodities histories, specifically that of sugar:http://www.commodityhistories.org/research/sugar-industries-cuba-and-java status of Cuba in world sugar market

Acknowledgments

- Warm thanks to Nancy Seasholes for her expertise and support.

- Heartfelt thanks to Allison E. Butler, JD, whose help in understanding the Sugar Trust and identifying sources was exceptional.