“Extraordinary Passage of the Flying Cloud“

in East Boston

Nathaniel Currier lithograph and watercolor, 1852

Courtesy of the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

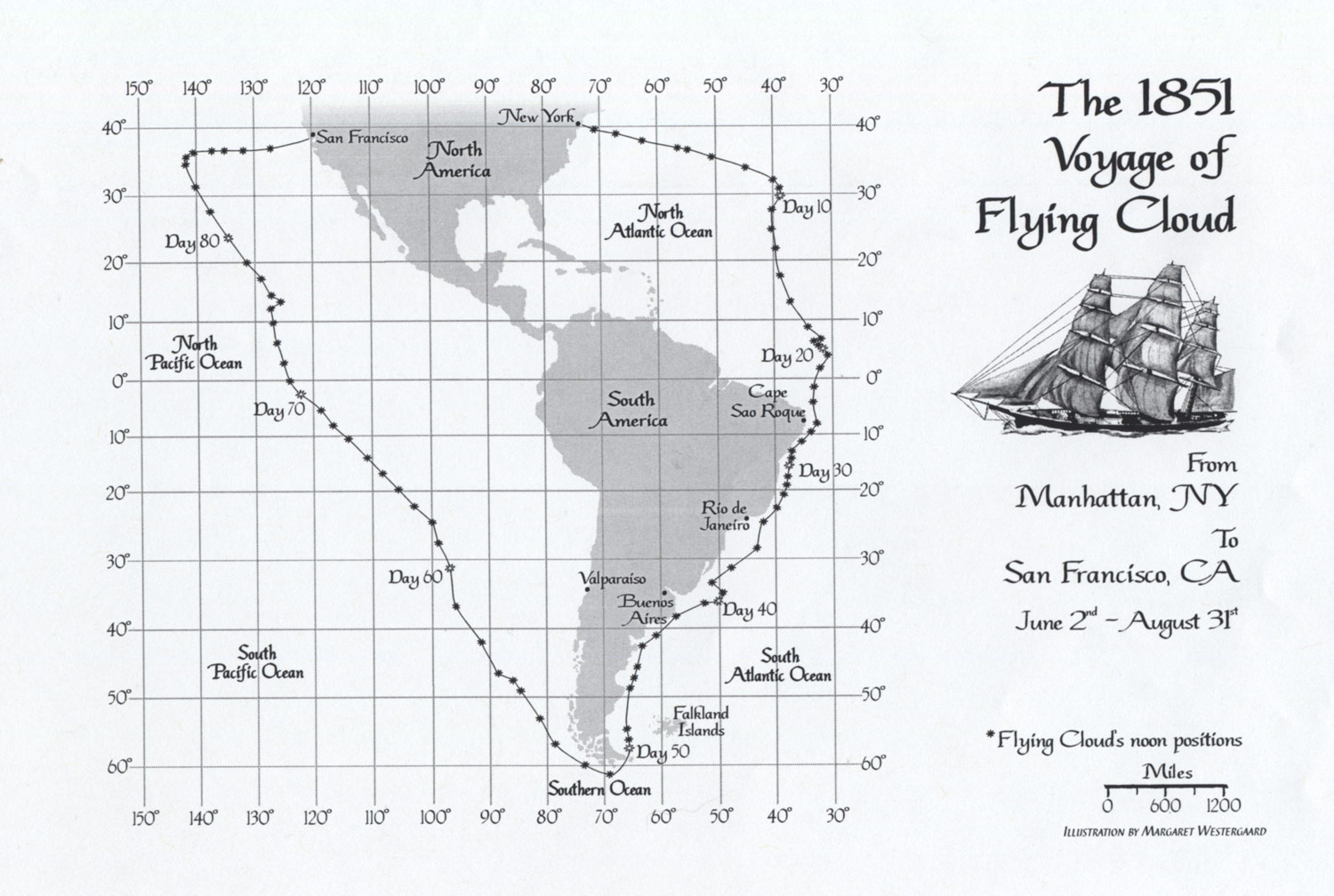

The 1851 New York Tribune headline trumpeted Flying Cloud’s record-breaking sail: 89 days 21 hours from New York around Cape Horn to San Francisco. There a newspaper described Donald McKay’s most famous clipper ship as “a monument of Yankee talent in ship building.” Flying Cloud, her captain Josiah Creesy and his wife, Eleanor, the ship’s navigator, would surpass their achievement 4 years later by 13 hours. No square-rigged ship has ever beat it; 135 years later a racing yacht did.

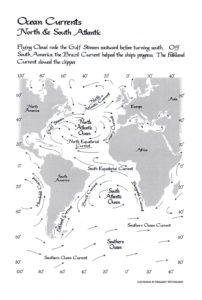

Eleanor Creesy’s expertise in navigation and her role in Flying Cloud’s success were exceptional for the times. Recognizing her intellect, Eleanor’s seafaring step-father had taught her navigation. She used her knowledge and the latest scientific data to chart Flying Cloud’s course into maritime history.

Between 1850 and 1858, Donald McKay built 31 clipper ships at his shipyard located along Border Street. Dozens more were built by other outstanding shipbuilders, earning East Boston the reputation as the birthplace of many of the fastest, most beautiful merchant sailing ships ever built.

Sign Location

More …

Resources

- Clark, Arthur Hamilton. The Clipper Ship Era. G. P. Putmans’ Sons, 1911.

- The Daily Alta California San Francisco Sep 1, 1851.

- Howe, Octavius T. & Matthews, Frederick C. Matthews. American Clipper Ships 1833-1858. Dover Publications, Inc. reprinted from Publication Number Thirteen of the Marine Research Society, 1926-27.

- O’Har, George Michael. “Shipbuilding, Markets and Technological Change in East Boston.” Doctoral Thesis, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, February 1995.

- New York Tribune Oct 5, 1951.

- Sacramento Daily Union April 24, 1854.

- Shaw, David. Flying Cloud: The True Story of America’s Most Famous Clipper Ship and the Woman Who Guided Her. William Morrow imprint of HarperCollins, 2000.

- Whipple, Addison Beecher Colvin. The Clipper Ships. Time-Life Books, 1980. p.51-54.

Acknowledgments

- Our gratitude to the Perkins School for the Blind and David W. Cook for their partnership in creating the audio files.

- Warm thanks to the late Edith DeAngelis for sharing her knowledge of East Boston history and mentioning, in passing, that a three-quarter replica of Flying Cloud was once tied up at the end of Lewis Street.