Ancestral Land

in Charlestown

Joshua Winer’s mural depicts Massachusett women and men engaged in seasonal encampment activities during the pre-Colonial era.

With permission of artist Joshua Winer

The First People lived in this region for thousands of years. Their descendants, the Massachusett, named what we now call Charlestown, Mishawum— “Great Springs.” They gathered here and at other harbor locations seasonally, to farm and hunt for food.

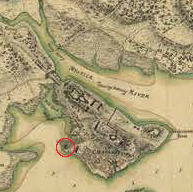

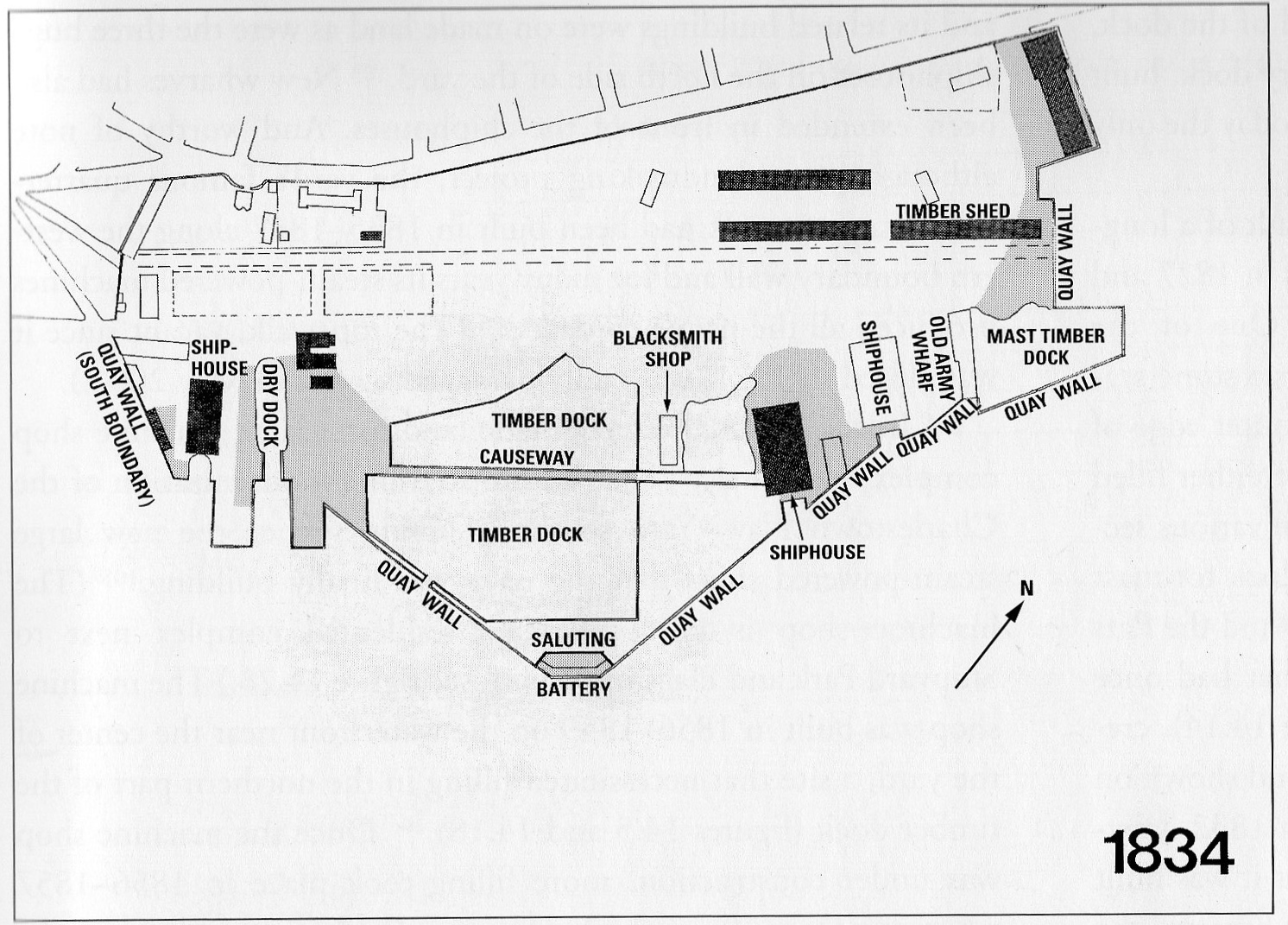

The English purchased Mishawum from the principle sac’hem, the “Queen of the Massachusett.” They renamed the peninsula and built homes around City Square. But this part of Charlestown remained as farm land until 1801, when the federal government bought it to establish the Charlestown Navy Yard. The Navy soon filled mudflats and marsh, making land for wharves and ship building. In the 1830s, seawalls were constructed along the outer edges of the mudflats. This marked the end of made land in this section of the Navy Yard; the seawall remains in place today, to your right.

The land, however, would undergo yet another transformation after the Navy Yard closed in 1974. In the decades since, housing has sprung up along the waterfront, where the Massachusett people once fished, harvested shellfish, and launched canoes.

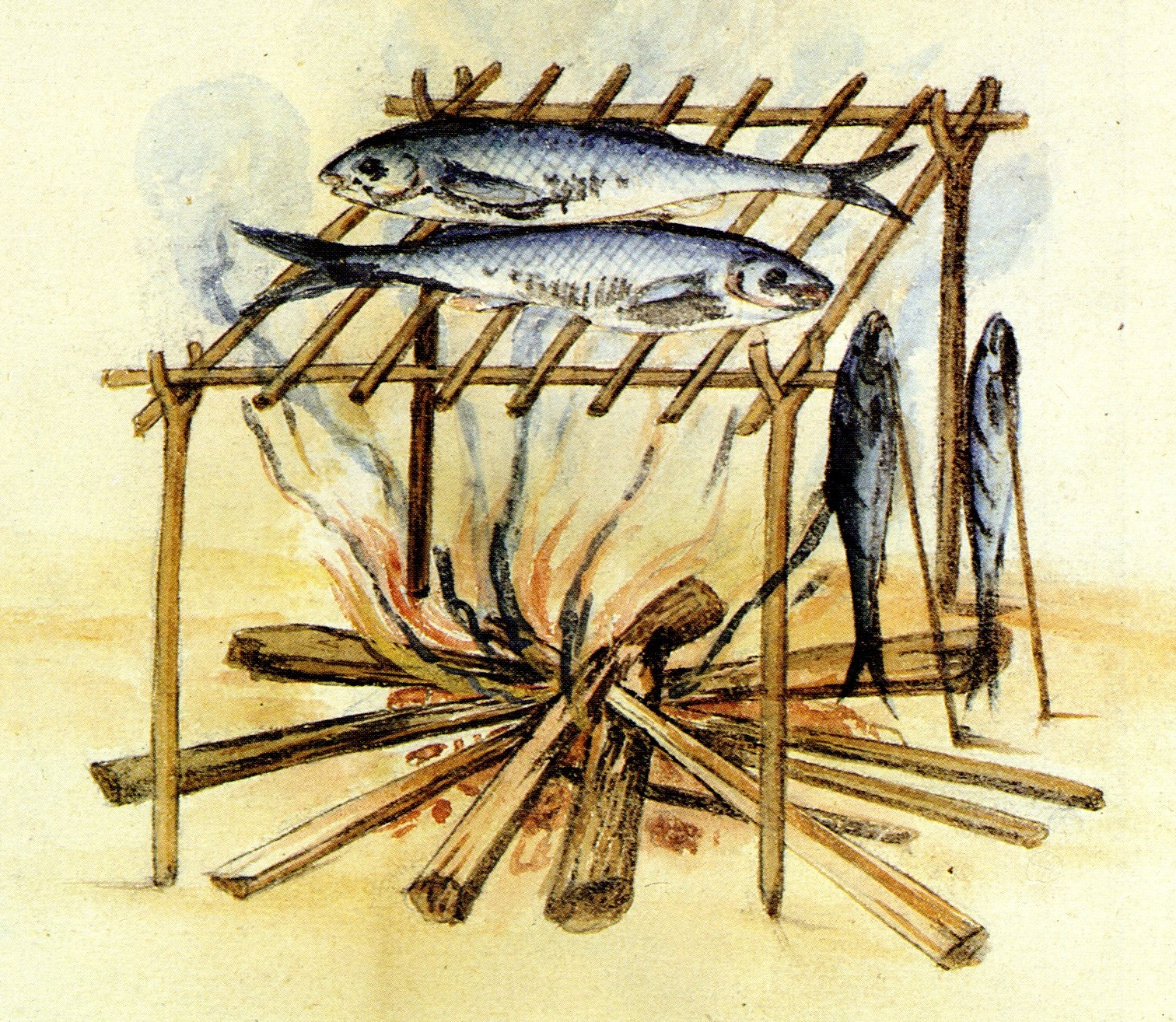

Like other coastal tribes, the Massachusett people both farmed and thrived on abundant marine resources in the estuary where fresh river water mixed with ocean water.

1585 illustration by John White of Native Americans living in present-day North Carolina. Published by Theodor de Bry in Americae pars decima.

July 17, 1605: “We anchored near an island where we observed many smokes along the shore…. There is a great deal of land cleared up and planted with Indian corn. The country is very pleasant and agreeable, and there is no lack of fine trees. The canoes of those who live there are made of a single piece, and are very liable to turn over if one is not skillful in managing them.”

From Voyage of Samuel de Champlain, 1604-1608, the French explorer’s journal. De Champlain is believed to have anchored between what is now Charlestown, a peninsula at the time, and East Boston, which was an island.

The Queen of Massachusett, principle sac’hem over all northern Massachusett bands, lived for a time in a small Indian village located in the area that is now Bunker Hill Community College.

Charlestown peninsula, detail from Sir Thomas Hyde Page map, 1775. Courtesy of Norman Leventhal Map and Education Center at Boston Public Library

Sign Location

More…

Resources

For an excellent overview of Native American history in the Boston area:

http://www.sec.state.ma.us/mhc/mhcarchexhibitsonline/massachusettsbay.htm

For an overview of archaeological finds from the Big Dig project:

https://www.sec.state.ma.us/mhc/mhcpdf/Big_Dig_book.pdf

For more information on Boston’s fish weir

http://www.theshawmutproject.org/BoylstonFishweir

“Archaeological Data Recovery, Town Dock Prehistoric Site [report],” Ducan Ritchie, Principal Investigator, The Public Archaeology Laboratory, Inc. Oct. 1994.

Bragdon, Kathleen. Native People of Southern New England, 1500-1650. University of Oklahoma Press, 1996.

“Cultural Landscape Report for Charlestown Navy Yard” National Park Service, Boston 2005.

Green, Ren. “The History of the Neponset Band of the Indigenous Massachusett Tribe,” and “The Northeastern Massachusett,” 2016.

Highway to the Past: The Archaeology of Boston’s Big Dig. Ed. Ann-Eliza H. Lewis. Published by William Gavin, chairman Massachusetts Historic Commission, 2001.

Salisbury, Neal. Indians of New England. Indiana University Press, 1982.

http://www.sec.state.ma.us/mhc/mhcarchexhibitsonline/massachusettsbay.htm

Acknowledgements

- Deep thanks to the Massachusett Tribal Council for their assistance with all aspects of this sign

- Translation and recording thanks to the generosity of the Boston Marine Society

- Our gratitude to the Perkins School for the Blind and David W. Cook for their partnership in creating the audio files