Women of the Navy Yard

in Charlestown

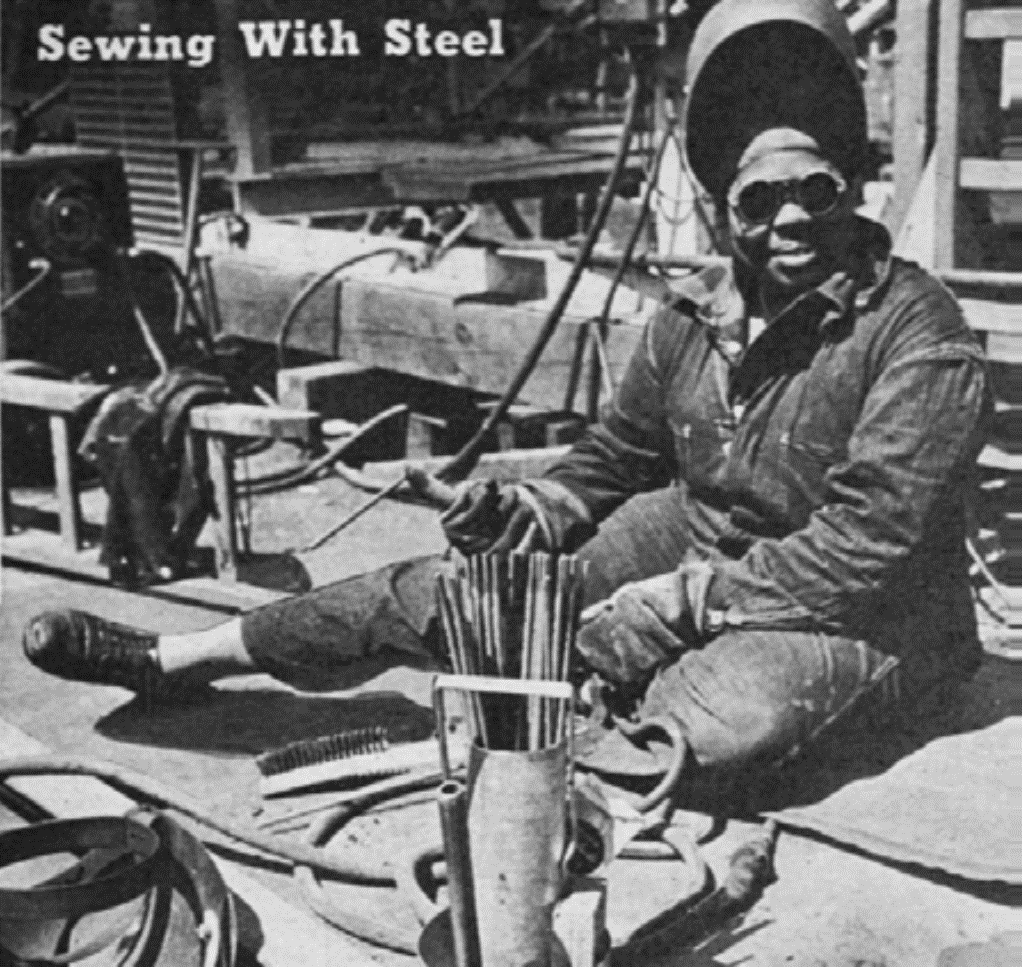

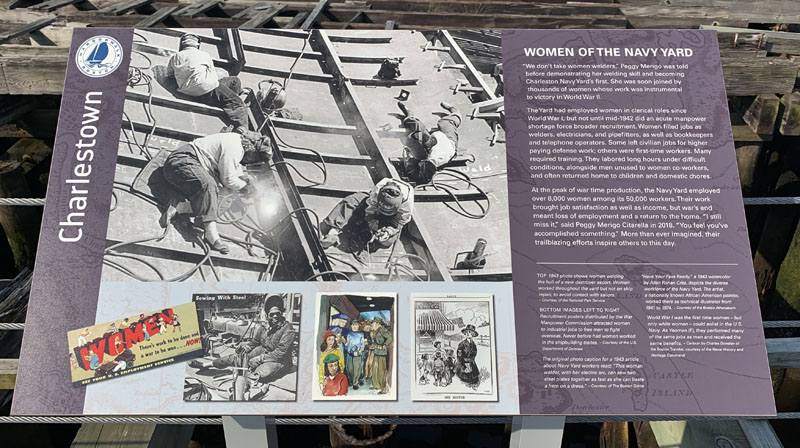

The 1943 photo shows women welding the hull of a new destroyer escort. Women worked throughout the yard but not on ship repair, to avoid contact with sailors.

Courtesy of the National Park Service

“We don’t take women welders,” Peggy Merigo was told before demonstrating her welding skill and becoming Charleston Navy Yard’s first. She was soon joined by thousands of women whose work was instrumental to victory in World War II.

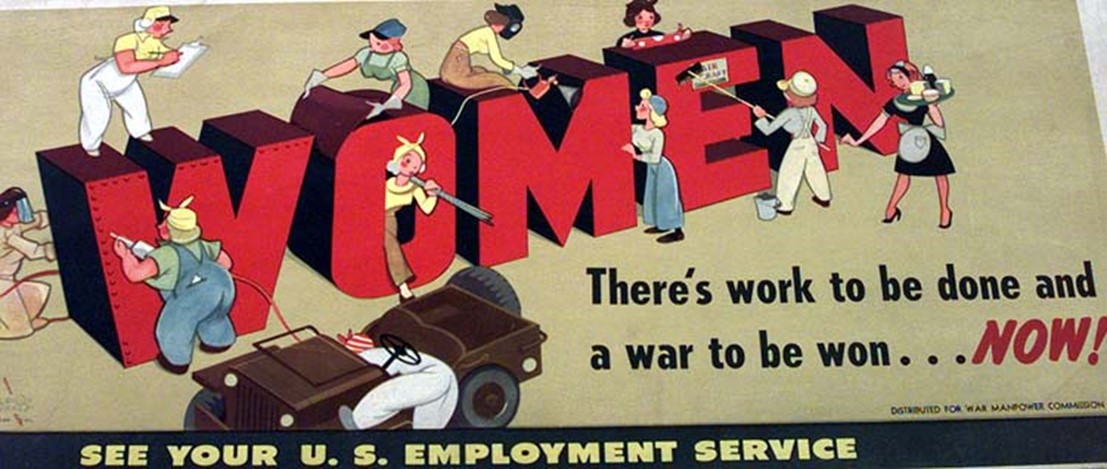

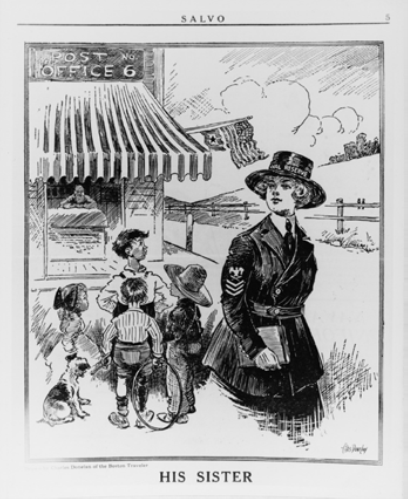

The Yard had employed women in clerical roles since World War I, but not until mid-1942 did an acute manpower shortage force broader recruitment. Women filled jobs as welders, electricians, and pipefitters, as well as bookkeepers and telephone operators. Some left civilian jobs for higher paying defense work; others were first-time workers. Many required training. They labored long hours under difficult conditions, alongside men unused to women co-workers, and often returned home to children and domestic chores.

At the peak of war time production, the Navy Yard employed over 8,000 women among its 50,000 workers. Their work brought job satisfaction as well as income, but war’s end meant loss of employment and a return to the home. “I still miss it,” said Peggy Merigo Citarella in 2018. “You feel you’ve accomplished something.” More than ever imagined, their trailblazing efforts inspire others to this day.

Sign Location

More …

Resources

- Akers, Regina T. The Navy’s First Enlisted Women: Patriotic Pioneers. Naval History and Heritage Command, 2019.

- Bernardo, Celeste. There Were No Sheila Shipfitters Gender Segregation at the Boston Navy Yard 1942-1945. 2001. Northeastern University, M.A. dissertation.

- Black, Frederick R. Charlestown Navy Yard 1890-1973, Vols I & II, Cultural Resources Management Study No. 20. Boston National Historical Park, National Park Service, U.S. Department of the Interior, 1988.

- Carlson, Stephen P. Charlestown Navy Yard Historic Resource. National Park Service, 2010.

- “Chief Yeoman (F) USNRF – World War I”, image description. Naval History and Heritage Command.

- https://www.history.navy.mil/content/history/nhhc/our-collections/art/travelling-exhibits/women-in-uniform-/chief-yeoman–f–usnrf—world-war-i1.html Accessed 5 Jan 2021.

- Daniel, Seth. “First Female Welder in Navy Yard, Was Not Ordinary.” Charlestown Patriot-Bridge, Sept. 1, 2016. https://charlestownbridge.com/2016/09/01/first-female-welder-in-navy-yard-was-not-ordinary/ Accessed 5 Jan 2021.

- Guerra, Cristela. “On Labor Day, a celebration of ‘Rosies,’ the women who kept the factories churning during WWII.” The Boston Globe, Aug. 30, 2018. https://www.bostonglobe.com/metro/2018/08/30/labor-day-celebration-rosies-women-who-kept-factories-churning-during-wwii/4C4IDSzDeeifw62TwSSMiO/story.html Accessed 5 Jan 2021.

- Gregory, Chester W. “The Problem of Labor During World War II: The Employment of women in Defense Production.” The Ohio State University Ph.D., 1969.

- Hannigan, David. “Boston Navy Yard and the “Great War,” 1914-1918.” Boston National Historic Park. https://www.nps.gov/articles/bny_wwi.htm Accessed 5 Jan 2021.

- Harvey, Sheridan. “Rosie the Riveter: Real Women Workers in World War II.” Library of Congress https://www.loc.gov/item/webcast-3350 Accessed 5 Jan 2021.

- Kienle, Polly. “”We Can Do It!” – Shipbuilding Women invade the Charlestown Navy Yard.” Boston National Historic Park. https://www.nps.gov/articles/cny-swons.htm Accessed 5 Jan 2021.

- MV Museum Oral History Channel, producer. Barbara Townes | Welding in WWII. Video https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=n5eaDXBAdBQ&t=316s Accessed 5 Jan 2021.

- Newman, Dorothy K. “Employing Women in Shipyards.” Bulletin of the Women’s Bureau, No. 192-6. United States Department of Labor, 1944.

- SWON: Shipbuilding Women of the Navy. Start date to March 2020. Charlestown Navy Yard Visitor Center, Boston National Historic Park.

-

Tziperman Lotan, Gal “Allan Rohan Crite was dean of Black artists in New England,” Boston Globe, February 2022.

- “Yeomen (F) Register to Vote.” Boston National Historic Park. https://www.nps.gov/articles/000/yeomen-f-register-to-vote.htm Accessed 18 Feb 2021.

- “Women Workers at the Boston Navy Yard during World War I.” Boston National Historic Park. https://www.nps.gov/articles/women-workers-bny-wwi.htm Accessed 5 Jan 2021.

Acknowledgments

- Thank you to Maria Cole and Polly Kienle of the National Park Service for their support and assistance.

- Our gratitude to the Perkins School for the Blind and David W. Cook for their partnership in creating the audio files.