Transformed Tidal Flats

in South Boston

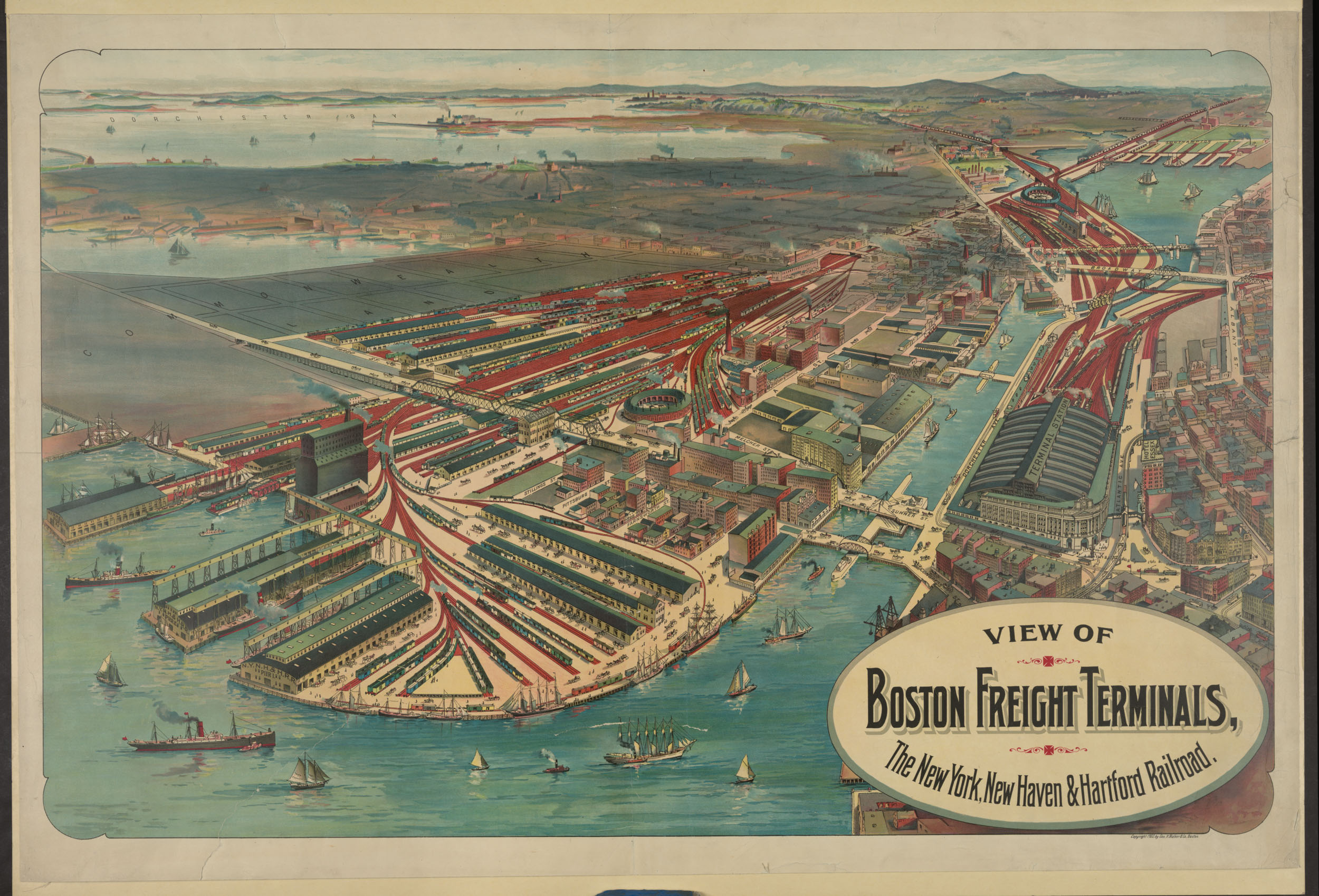

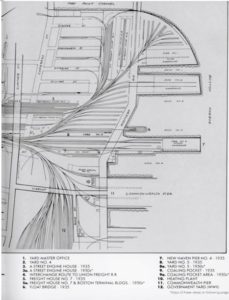

Like most large piers in Boston around 1900, Pier 4 and Piers 1 and 2 (now Fan Pier) were owned by a major railroad company. The New York, New Haven & Harford Railroad Company, whose terminal is pictured here, was widely known as “the New Haven.”

Print by George H. Walker & Co., 1903. Courtesy of the Library of Congress

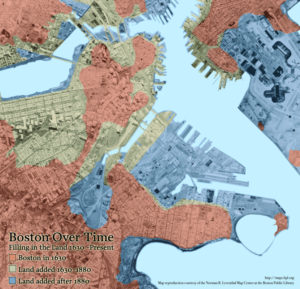

In 1873, major seawall construction and filling began between Fort Point Channel and here, part of a massive landmaking project on the South Boston Flats. Soon, a vast rail yard covered the former mud flats and salt marsh. To facilitate freight handling, tracks stretched onto Pier 4—built in the 1880s—and the two piers that today comprise Fan Pier. A series of railroad companies, culminating with the New Haven, owned both land and piers.

Coal was a vital regional power source at the time. In 1900, for example, four million tons were shipped up the coast to Boston. A portion was unloaded here to be transported by freight car. Other goods arriving at Pier 4 included imported wool, stored in warehouses nearby, animal hides destined for shoemaking factories, and cotton headed for mills.

The New Haven went bankrupt in 1935, reorganized, and was bankrupt again in 1961. In the years that followed, tracks were torn up and replaced by parking lots. Around 2010, an unprecedented building boom began to transform what was once tidal lands yet again.

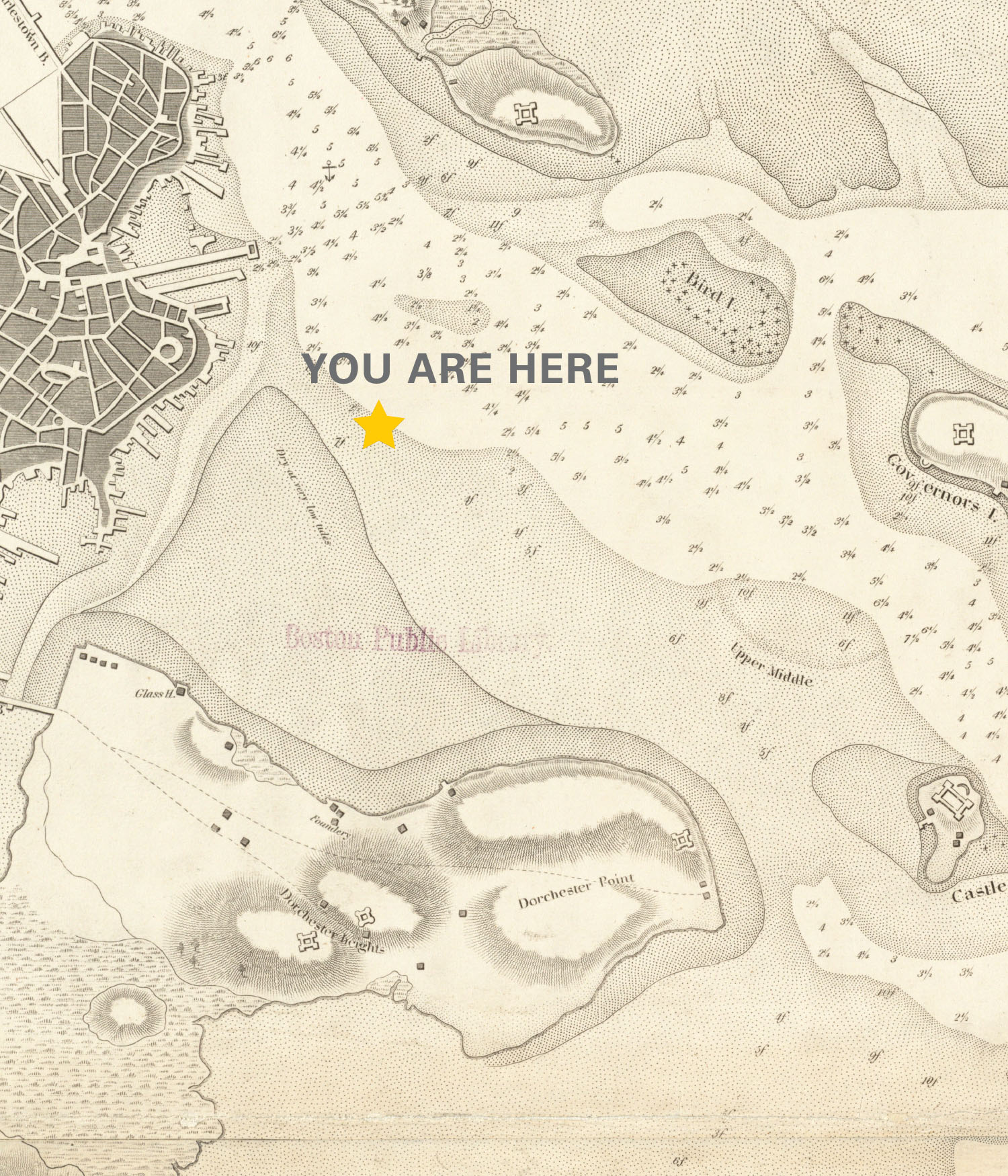

The 1817 survey of Boston Harbor shows a smattering of houses in a rural South Boston and the enormous tidal flats known as South Boston Flats. By the end of the 19th century, the flats were filled. Across the harbor, Bird and Governor’s Islands would become part of Logan Airport.

Boston Harbor Chart by Alexander Wadsworth, published in 1819. Courtesy of the Norman B. Leventhal Map & Education Center, Boston Public Library

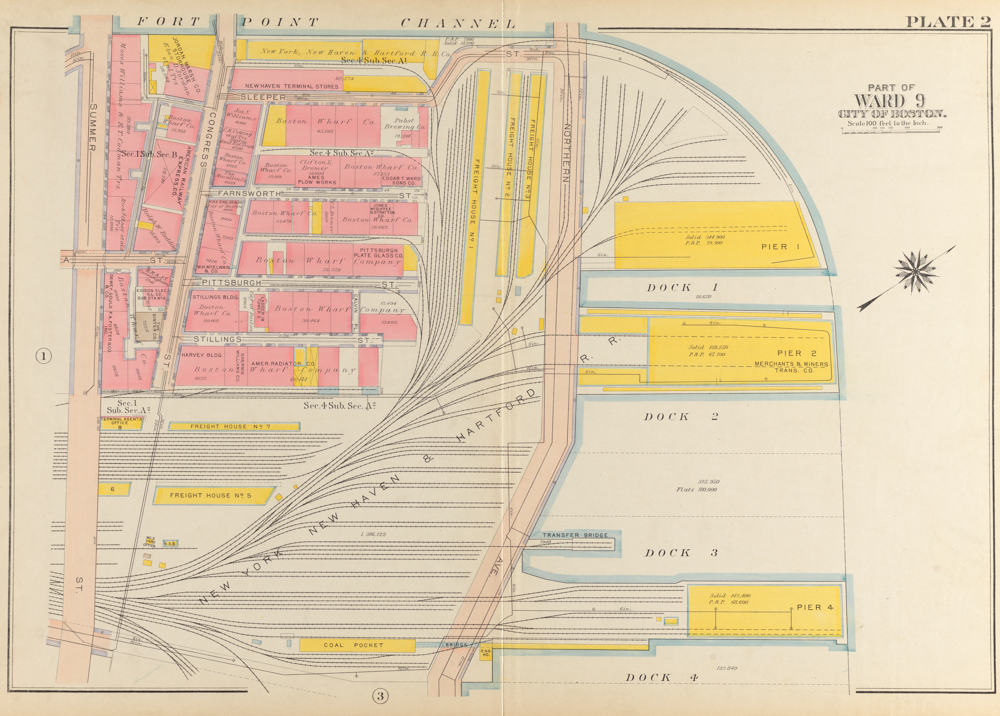

Everything shown on this 1919 map is new land. The original South Boston shoreline was roughly along First Street. Total landmaking in South Boston was second only to what was required to create Logan Airport.

Atlas of the City of Boston, South Boston by G. W. Bromley & Co., Courtesy of the Norman B. Leventhal Map & Education Center, Boston Public Library

New England’s high demand for coal after the Civil War drove the construction of ever-larger schooners to carry coal up the coast from Virginia. In this photograph taken from East Boston, a five-masted schooner is docked at Pier 4, delivering coal. The tall building to the right is a grain elevator.

Photograph by Henry G. Peabody, Detroit Publishing Co, 1906. Courtesy of the Library of Congress

Sign Location

More …

Resources

- Boston Landmarks Commission. “Fort Point Channel Landmark District Study Report.” City of Boston, December 9, 2008.

- Brown, C.A. “South Boston and the New Haven,” Shoreliner, 1986.

- Bunting, W.H. Portrait of a Port: Boston, 1852-1914. Belknap Press, Harvard University Press, 1971.

- Gillespie, C. Bancroft. Illustrated History of South Boston. Inquirer Publishing Company, 1900.

- Liljestrand, Robert A. The New Haven Railroad’s Boston Division. Published by Bob’s Photo, 2001.

- Seasholes, Nancy S. Gaining Ground: A History of Landmaking in Boston. The MIT Press, 2003.

- Toomey, John & Edward Rankin. History of South Boston (Its Past and Present) and Prospects for the Future. Published in Boston by the authors, 1901.

- “Thirty-fifth Annual Report of the Board of Harbor & Land Commissioners for the Year 1913.” Boston, MA

- “Twenty-ninth Annual Report of the Harbor & Land Commissioners for the Year 1907.” Boston, MA

- “First Annual Report of the Commission on Waterways & Public Lands: Consolidating Harbor & Land Commission and Directors of the Port of Boston, for the Year 1916.” Boston, MA

Acknowledgments

- Warm thanks to Nancy Seasholes for her expertise and support.

- Our gratitude to the Perkins School for the Blind and David W. Cook for their partnership in creating the audio files.