The Nantasket Steamboat

in the Wharf District

(awaiting installation)

The S.S. Nantasket was one of a fleet of wooden paddle-wheel steamboats that plied between Rowes Wharf and Nantasket. Built in Chelsea, it could carry 2,000 passengers.

Courtesy of the Boston Public Library, Leslie Jones Collection

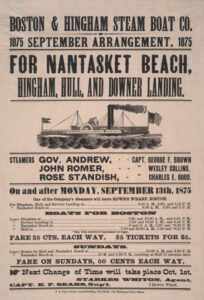

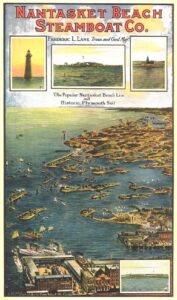

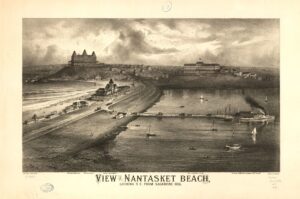

For more than 150 years, Rowes Wharf has been the departure point for boats heading across Boston harbor to towns on the South Shore. Generations of Bostonians have closely associated Rowes Wharf with the boat to Nantasket. Eager to escape the city’s summer heat, they arrived here by horse cars, carriages, trolleys, or walked from South Station.

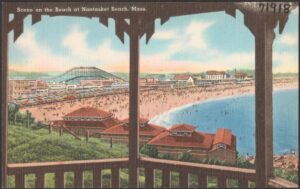

The 90-minute, 15-mile cruise on steam-powered paddle-wheelers glided passengers past the harbor islands to Nantasket’s four miles of sand, its ornate Gilded Age hotels, and later its beloved amusement park that stood between the steamboat landing and the beach.

“We took the Nantasket boat every summer,” one Bostonian recalls. “My grandmother packed a huge lunch for us. Late afternoon, we climbed back onto the boat, sunburned and happy, and slept most of the way home.”

By the 1960s, the sidewheelers gave way to diesel-powered commuter boats and dinner cruises, even as the old wooden passenger sheds were replaced by an elegant new Rowes Wharf.

When Paragon Park opened in 1905, it boasted a Japanese village, camel rides, a lagoon and sideshows. As tastes changed, a roller coaster, bumper cars and a carousel were introduced. Though the park closed in 1985, the carousel with its hand-carved flying horses was saved and still whirls nearby.

Courtesy of Boston Public Library

Sign Location

More ...

Resources

- Advertisement for boats to Nantasket, Boston Evening Transcript, August 31, 1881.

- Barr’s Postcard Journal, William and Elaine Pepe, September 2017.

- Boston Globe, Johana Seltz, December 10, 2009.

- Bradlee, Francis Boardman Crowninshield, Some Account of Steam Navigation in New England,1923.

- Building Provincetown, David W. Dunlap, 31 December 2009.

- Bunting, W.H. Portrait of a Port: Boston, 1852-1914. Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press, Harvard University Press, 1971.

- Del Ponte, Jimmy. “Paragon Park,” The Somerville Times, May 14, 2020.

- Harden, Chris, The History of Paragon Park, self-published 2021.