No Escape from Gigantic Molasses Wave

in the North End

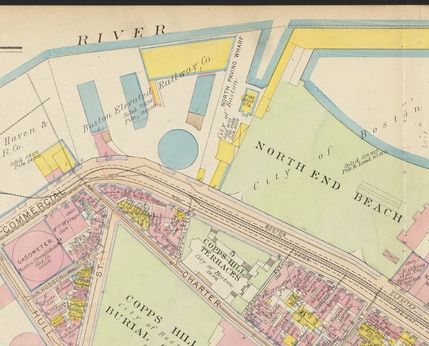

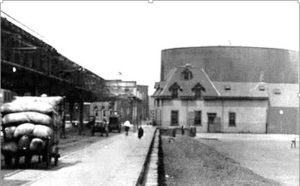

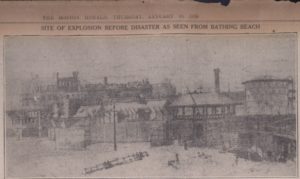

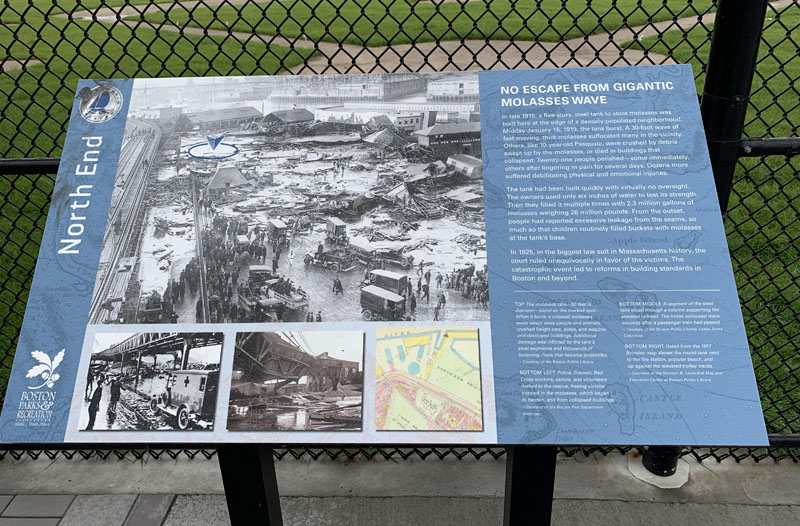

The molasses tank—90 feet in diameter— stood on the marked spot. When it burst, a colossal molasses wave swept away people and animals, crushed freight cars, autos, and wagons, and destroyed buildings. Additional damage was inflicted by the tank’s steel segments and thousands of fastening rivets that became projectiles.

Courtesy of the Boston Public Library

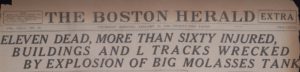

In late 1915, a five-story, steel tank to store molasses was built here at the edge of a densely-populated neighborhood. Midday January 15, 1919, the tank burst. A 30-foot wave of fast-moving, thick molasses suffocated many in the vicinity. Others, like 10-year-old Pasquale, were crushed by debris swept up by the molasses, or died in buildings that collapsed. Twenty-one people perished—some immediately, others after lingering in pain for several days. Dozens more suffered debilitating physical and emotional injuries.

The tank had been built quickly with virtually no oversight. The owners used only six inches of water to test its strength. Then they filled it multiple times with 2.3 million gallons of molasses weighing 26 million pounds. From the outset, people had reported excessive leakage from the seams, so much so that children routinely filled buckets with molasses at the tank’s base.

In 1925, in the biggest law suit in Massachusetts history, the court ruled unequivocally in favor of the victims. The catastrophic event led to reforms in building standards in Boston and beyond.

Sign Location

More …

Resources

- Daley, Jason. ”The Sticky Science Behind the Deadly Boston Molasses Disaster,” Smithsonian Magazine. November 28, 2016.

- Mayville, Ronald A. “The Great Boston Molasses Tank Failure of 1919,” Civil + Structural Engineer Media, September 1, 2014.

- McCann, Erin. “Solving a Mystery Behind the Deadly Tsunami of Molasses,” The New York Times. November 26, 2016.

- Morgenroth, Lynda. Boston Firsts: 40 Feats of Innovation and Invention that Happened First in Boston and Helped Make America Great. Beacon Press, 2006.

- Puleo, Stephen. Dark Tide: The Great Molasses Flood of 1919. Beacon Press, 2003.

- Schworm, Peter. “Nearly a century later, structural flaw in molasses tank revealed,” The Boston Globe. January 14, 2015.

- The day after the tank ruptured:

- https://www.flickr.com/photos/boston_public_library/4901511605/in/album-72157624622085789/

- https://www.flickr.com/photos/boston_public_library/4902097496/in/album-72157624622085789/

- For more of the story:

- Boston Globe centennial overview

- https://www.bostonmagazine.com/news/2019/01/12/molasses-flood-plaque/

- The Guardian’s centennial overview

Acknowledgments

- Warm thanks to Stephen Puleo for his assistance and support.

- Our gratitude to the Perkins School for the Blind and David W. Cook for their partnership in creating the audio files.

- Thank you to the Boston Marine Society for funding the Spanish and Italian translations as well as the recording of this sign.