Moving People and Goods

in the Wharf District

(awaiting installation)

The Elevated Atlantic Avenue segment operated from 1901 to 1938. Rowes Wharf station is in the foreground; State Street station to the north.

Courtesy of the Robert Stanley Collection

The construction of Atlantic Avenue along the waterfront in 1870 helped improve Boston’s transportation infrastructure. Two years later, Union Freight Railway tracks were added down the middle, connecting Boston’s north and south rail terminals. Spurs onto wharves and to warehouses facilitated transfer of goods. But the street-level track proved so dangerous that city officials restricted the number of rail cars and the train’s hours of operation.

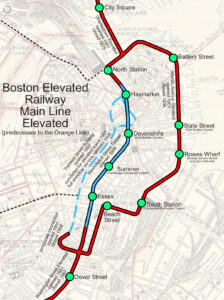

The Boston Elevated Railway Atlantic Avenue route, installed right above the freight line was less controversial. It helped meet the needs of Boston’s rapidly expanding population. With stations at key wharves, “the El” connected people to harbor ferries as well as steamship lines to destinations like Nantasket Beach, Philadelphia, New York, and Portland, Maine.

For decades, you could hop off a trolley at Rowes Wharf station, cross the harbor to East Boston by ferry, and then board the popular narrow gauge train to Revere Beach. Today, a ferry runs to Hingham, water taxis take you wherever you wish, and vessels can be chartered for cruises around the harbor and beyond.

Sign Location

More ...

Resources

- Beaucher, Steven. Boston in Transit: Mapping the History of Public Transportation in the Hub. WardMaps LLC, 2020.

- “The Wholesale Produce Markets at Boston, Mass.” U.S. Department of Agriculture, Production & Marketing Administration, Washington, DC., June 1950.

- Kyper, Frank. “Boston’s Anonymous Railroad Reached the End of the Track,” in The Railway and Locomotive Historical Society Bulletin, No. 123. October 1970. p. 58-61.

- Kyper, Frank. The Railroad That Came Out at Night. The Stephen Greene Press, 1977.

- “Report of the Commission on Metropolitan Improvements,” 1907.

- “Report of the Directors of the Port of Boston,” year ending November 30, 1914.

- Seasholes, Nancy S. Gaining Ground: A History of Landmaking in Boston. The MIT Press, 2003.

- Seasholes, Nancy S. ed. The Atlas of Boston History, University of Chicago Press, 2019.

- “The Traffic World,”1915.

Acknowledgments

Warm thanks to Steven Beaucher for his expertise.