Harbor Towers Rise

in the Wharf District

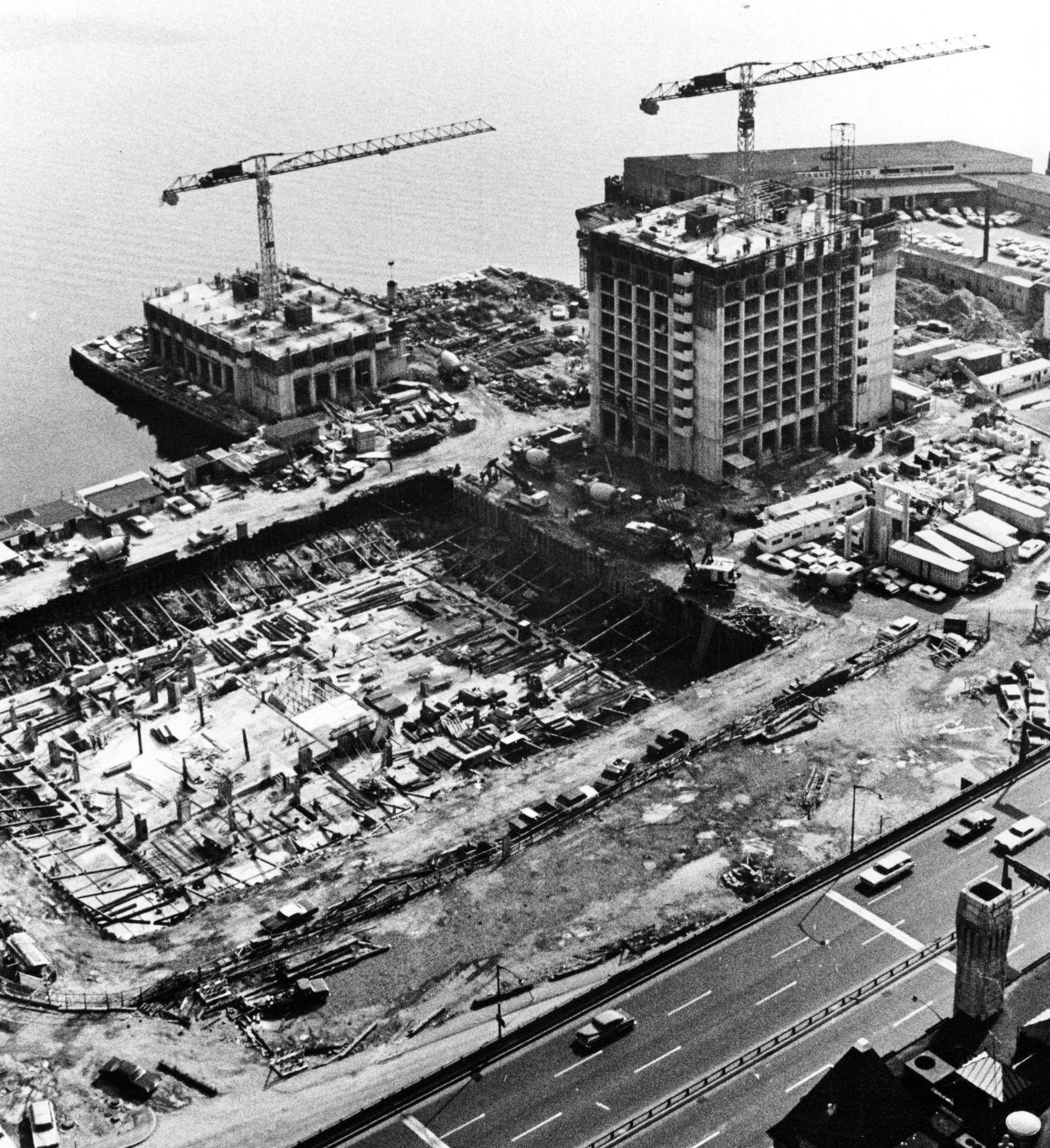

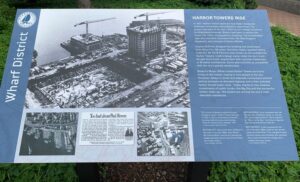

As part of Boston’s waterfront urban renewal program, Harbor Towers was built in 1970-71 with a combination of Federal Housing Authority and private monies. Photo by Charles Dixon, October 1970.

Courtesy of Boston Globe Archives

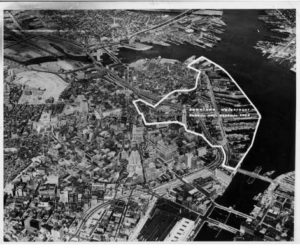

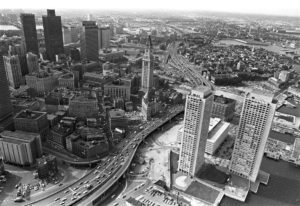

In 1971, Harbor Towers were the first major residential buildings constructed along Boston’s waterfront. The project was part of the city’s effort to turn things around on its dilapidated wharves. Boston had been in decline like many U.S. cities, its population dropping. The revitalization plan also included Christopher Columbus Park, the New England Aquarium, and renewal of Quincy Market.

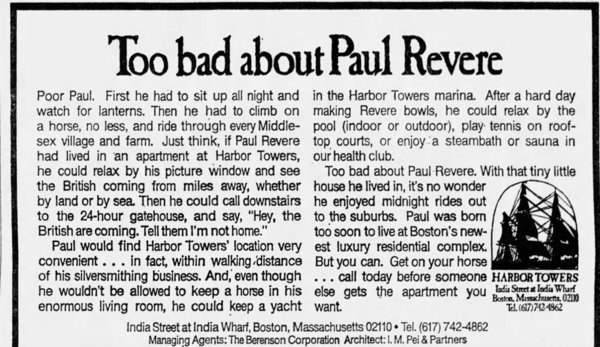

Charles Bulfinch designed the building that stood upon India Wharf for 155 years. Similarly, highly regarded Henry Cobb of I. M. Pei & Partners was chosen as the architect for Harbor Towers. Cobb’s design came midst the city’s bold—though short-lived—experiment with concrete modernism or Brutalist architecture. Some saw concrete as compatible with the city’s granite warehouses.

Boston’s Mayor White touted Harbor Towers as luxury living on the harbor, hoping to lure people to the city. However, delays in street and sidewalk connections and the setting between a then-polluted harbor and elevated highway forced lower rents. Today, thanks to two massive investments of public funds—the Big Dig and the successful harbor clean-up—the towers are among the city’s most desirable residences.

A plan proposed by the city in the early 1960s called for four shorter towers on India Wharf. This changed to three 40-story towers and ultimately two. Architect Henry Cobb lamented the change, explaining that two towers “don’t have the same compositional interest” as his pinwheel plan. But it did create more open space.

Courtesy of City of Boston Archives

Sign Location

More …

Resources

- For more on Brutalist architecture

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Brutalist_architecture

- https://mymodernmet.com/brutalist-architecture/

- Boston Globe archives at Northeastern University

- Keohane, Joe. “Towering Contradictions,” Boston Magazine, February 2008, p 112-115.

- Kifner, John. “On Boston Waterfront, Instant Neighborhood Glitters,” The New York Times, October 23, 1976.

- Pasnik, Mark; Michael Kubo, and Chris Grimley. Heroic: Concrete Architecture and the New Boston. The Monacelli Press, 2015.

- Yulis, Anthony. “Harbor Apartments 2 Years Away,” Boston Globe, February 7, 1969.

- Yulis, Anthony. “Harbor Apartments “Going Like Hot Cakes,” Boston Evening Globe, April 8, 1971.

- Yulis, Anthony. “Apartments on waterfront draw large Boston crowds,” Boston Globe, April 9, 1971.Yulis, Anthony. “Harbor Towers 75% rented,” Boston Sunday Globe, July 29, 1973.