Freedom by Sea

in South Boston

(awaiting installation)

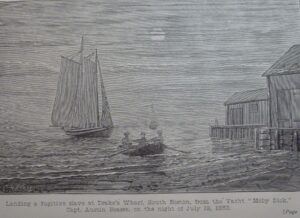

Drake’s Wharf once stood on the opposite side of Fort Point Channel from here. It was one of several places along Boston’s waterfront where self-emancipated individuals came ashore with the help of Boston’s abolitionists.

Bearse, Austin. Reminiscences of Fugitive-Slave Days in Boston, 1880

“It cannot be that I shall live and die a slave. I will take to the water. This very bay shall yet bear me into freedom,” wrote Frederick Douglass of his hope to escape slavery by ship.

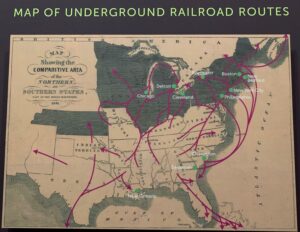

Escape was fraught with danger even for those making the journey to freedom by sea. Thousands took advantage of their work on the waterfront, proximity to waterways, boating skills, or contacts to escape bondage on a northbound ship. Some encountered sympathetic captains or crew members; others paid for their passage. Many hid on a vessel, unbeknownst to captain or crew. Boston and New Bedford with strong communities of Black activists and Underground Railroad networks were favored destinations.

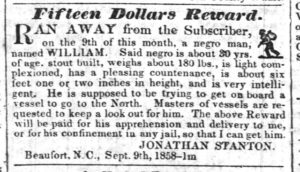

Southern states passed Negro Seamen Acts—jailing Black mariners while their ships were docked to prevent contact with the enslaved. Departing vessels were searched. Even after reaching Boston Harbor, some freedom seekers were detained on ships and then returned South. Nevertheless, many courageous, resourceful runaways succeeded—in one case by swimming to safety on one of the Boston Harbor islands.

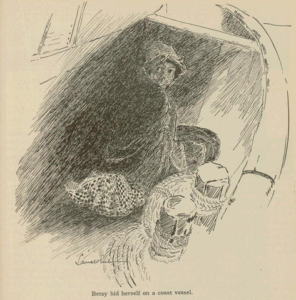

“‘You had better come out! I am going to smoke the vessel!’ I heard him call, but my mind was liberty or death.” Elisabeth [Betsy] Blakeley lay hidden below deck when she heard her enslaver board the ship and shout. She withstood three fumigations—a mix of sulphur and tobacco—before her enslaver gave up, and the ship sailed to Boston.

Recounted by Wendell Phillips in Reminiscences of Fugitive-Slave Days in Boston, by Austin Bearse, 1880

“I slipped myself between two bales of cotton, with the deck above me… and just then a bale was placed at the mouth of my crevice and shut me in a space about 4 ft by 3 ft. I then heard them gradually filling up the hold; and at last the hatch was placed on, and I was left in total darkness.”

John Andrew Jackson had to reveal himself within days, and the captain was determined to put him off as soon as he encountered a south bound vessel. It didn’t happen. And on Feb 10, 1847, when the ship docked in Boston, Jackson stepped ashore.

[

Jackson, John Andrew. The Experience of a Slave in South Carolina,1862

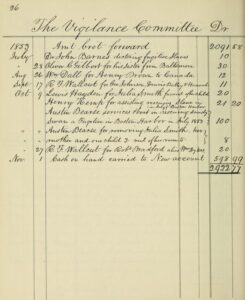

The third Boston Vigilance Committee formed in 1850 “to assist fugitive slaves.” In the decade that followed, dedicated abolitionists (Black and white) aided almost 450 fugitives, paying for their rescue, room and board, clothing, and for some, tickets to Canada.

Account Book of Francis Jackson, treasurer of The Vigilance Committee of Boston

Sign Location

More ...

Resources

- Account Book of Francis Jackson, treasurer of the Vigilance Committee of Boston

- Bardes, John. “Sailing While Black”

- Bearse, Austin. Reminiscences of Fugitive-Slave Law Days in Boston, Printed by W. Richardson, 1880.

- Cecelski, David S., “The Shores of Freedom: The Maritime Underground Railroad in North Carolina, 1800-1861,” The North Carolina Historical Review, Vol. 71, No. 2 (APRIL 1994), pp. 174-206

- Maritime Underground Railroad in NC.pdf

- Digital Library of American Slavery, North Carolina Runaway Slave Notices 1750-1865 dlas.uncg.edu

- "Escape of a Fugitive Slave from a Vessel in Boston Harbor,” The Liberator. 31 December 1858.

- Jackson, John Andrew. Experiences of a Slave in South Carolina, 1862. Includes his escape by ship to Boston

- Walker, Timothy D. Ed. Sailing to Freedom, Maritime Dimensions of the Underground Railroad. University of Massachusetts Press, 2021.

- https://www.nps.gov/articles/maritime-underground-railroad-in-boston.htm

- https://app.freedomonthemove.org/search?limit=12&page=9&q=vessel for runaway slave ads noting vessels

- https://guides.loc.gov/chronicling-america-fugitive-slave-ads

Acknowledgments

Warm thanks to NPS historian Shawn Quigley and University of Massachusetts, Dartmouth, professor of history Timothy Walker for their guidance and expertise.