Crossing the Harbor

in East Boston

Noddle Island steaming toward East Boston, 1911

Courtesy of Historic New England

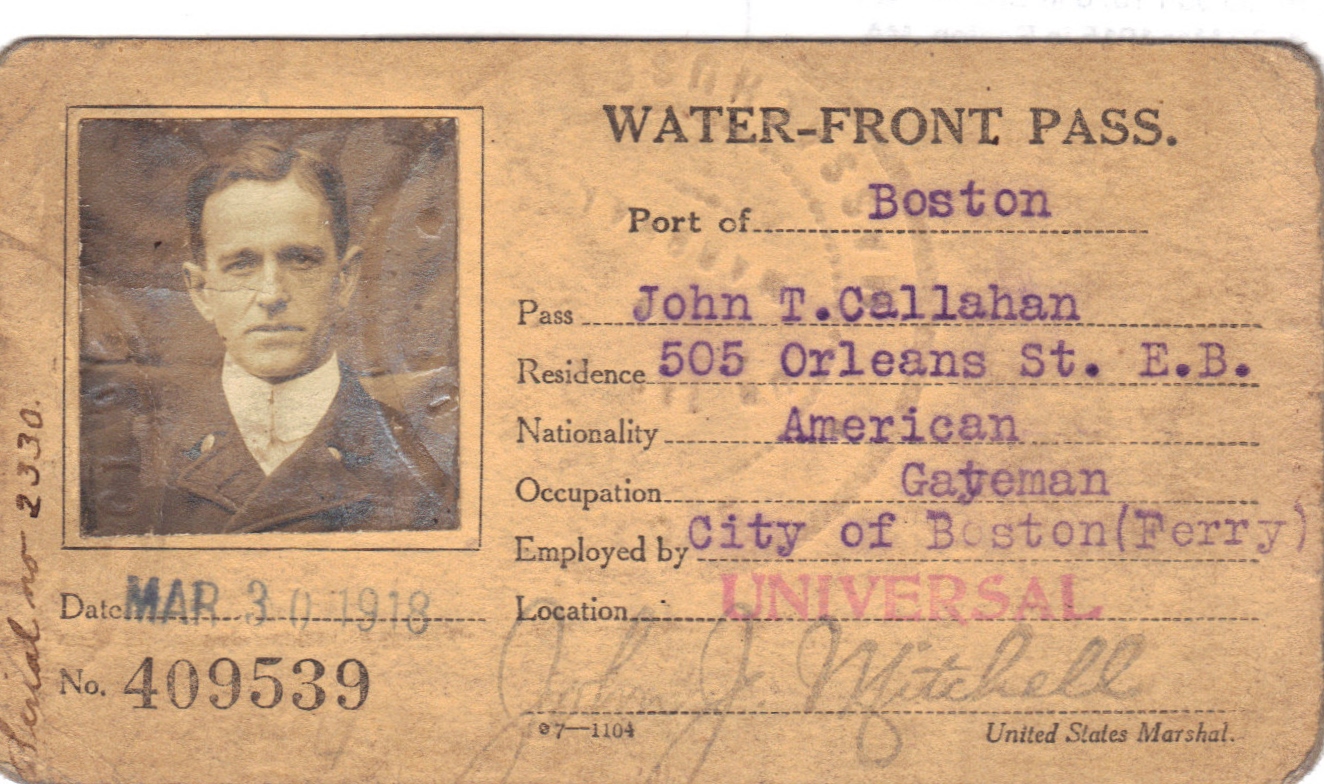

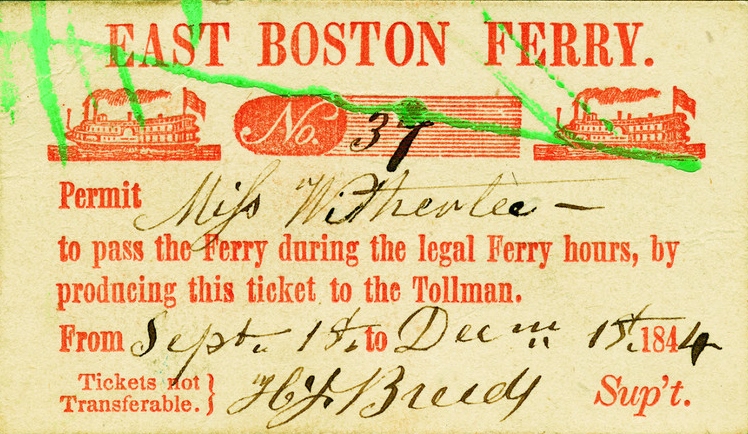

For 118 years, ferries connected East Boston to Boston’s downtown waterfront. In fact, the first vessel built here was a ferry, the East Boston, launched in 1834. At one time three separate routes were operating—an essential part of East Boston life.

“My grandfather used to collect fares for the ferry ride, one cent for a person, free on July 4th,” recalled one resident. “A horse and team cost five cents. The ferries were always packed with passengers, horses and teams, an occasional model T, and pushcarts.”

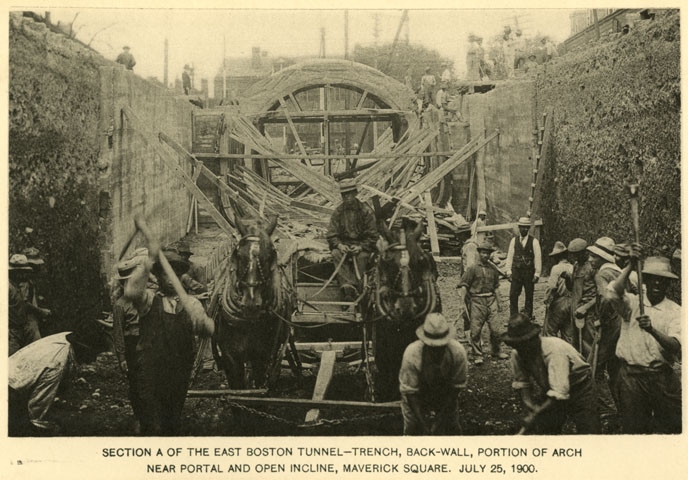

In 1904, a streetcar tunnel under the harbor—now the Blue Line—opened. It was the first underwater subway in the U.S. It was not for everyone, however. “My mother was terrified of going through the tunnel,” an East Boston teacher remembered. “She always took the ferry and sat in the companionway so her hat would not blow off.” When the Sumner Tunnel opened in 1934, the ferry’s years were numbered. The last East Boston ferry crossed in 1952.

“As a youngster, I sold newspapers on the Lewis Street Ferry. I always enjoyed being up front and watching the pilot throw the ship’s props into reverse which would churn up a tremendous wake and then the ferry would slam into these huge telephone-pole-type timbers and slide into the dock.” (Mario Carco, Melrose Mirror, November 1999)

Sign Location

More …

Resources

- Sumner, William H. History of East Boston: With Biographical Sketches of its Early Proprietors, and an Appendix. Boston: William H. Piper and Company, 1858.

Acknowledgments

- Our gratitude to the Perkins School for the Blind and David W. Cook for their partnership in creating the audio files.

- Thank you to Nancy Seasholes for her expertise and support.