Boston’s Longshoremen

in South Boston

(awaiting installation)

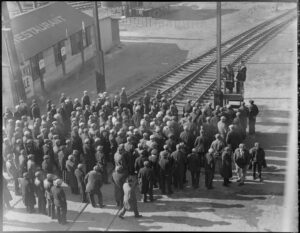

Men hoping to be hired gather at Commonwealth Pier in 1935, a process known as a “shape up.” A foreman, called a “walking boss,” hired gangs of about 21 men. Getting work depended on knowing the foreman who typically chose men from his own ethnic background. It was very hard for a newcomer to break in.

Courtesy of Boston Public Library, Leslie Jones Collection

For decades, Boston wharves like Commonwealth Pier swarmed with longshoremen loading and unloading ships. They were hired by ship owners from “along the shore,” especially after the 1840s when sailing vessels whose large crews handled their own cargo gave way to steamships with smaller crews.

Cargoes ranged from bulk freight to passengers’ luggage. It was back-breaking, dangerous, dirty work. Longshoremen waited near the docks or in saloons used as hiring halls, never knowing when a ship might arrive or at which wharf. Novelist Theodore Dreiser wrote, “You see them in sun or rain, on hot days or cold ones, waiting.”

Hired for one ship at a time, longshoremen had no guarantees of steady work and were often poor despite their key role in Boston’s economy. This led to the formation of the Boston Longshoreman’s Provident Union in 1847, the first longshoreman’s union in the United States.

By the 1970s, massive container ships were transporting most sea freight. Ship-to-shore cranes replaced workers on the docks and far fewer longshoremen were needed.

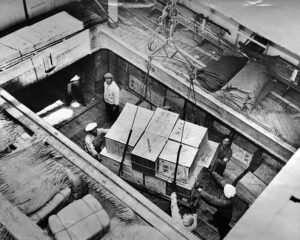

Longshoremen worked in well-organized gangs to get freight on and off ships efficiently. Shifts lasting 20 to 30 hours could begin and end at any time with short breaks only for meals. Longshoremen worked under the unrelenting pressure that “the ship must sail on time.”

Courtesy of Museum of Industry and History

“Growing up in a ‘dockworker’s family,’ I witnessed firsthand the struggles and challenges that union longshoremen in our country had to endure. They had to fight powerful shipping executives for dignity and respect, and the mob bosses who wanted to control the union in the Port of Boston.”

From “”A Longshoreman’s Son Remembers” by Raymond Flynn, Boston mayor 1984-1993. The Irish Echo, September 22, 2011

The amount of weight allowed in a ‘sling load’ was a contentious issue. Steamship agents wanted larger weights to speed cargo handling; longshoremen, citing safety concerns, demanded a top limit of 1,000 pounds. That dispute led to a nine-week strike in 1931. The Governor of Massachusetts brought in Black laborers as strikebreakers inflaming racial tensions among the then all-white longshoremen’s union.

Courtesy of the National Museum of American History

Longshoremen were assigned to the hold, the deck or the dock. Working in the hold, one longshoreman recalled, “that was the dogs. That was the worst. Cold in the wintertime, hot in the summer. They thought the men in the hold was the lowest.”

Courtesy of San Francisco History Center. Recollection by Roy Saunders as quoted by Bruce Nelson in Divided We Stand: American Workers and the Struggle for Black Equality

Sign Location

More ...

Resources

- Barnes, Charles Brinton & Pauline Dorothea Goldmark, The Longshoremen. Russell Sage Foundation, NY, 1915.

- Donovan, Arthur. “Longshoremen and Mechanization,” Journal for Maritime Research, December 1999.

- Dreiser, Theodore. “The Color of a Great City,” New York: Boni & Liveright, 1923.

- Esme, Haven. “What Does a Longshoreman Do?” PracticalAdultInsights.com, January 2023.

- Flynn, Ray. “A Longshoreman’s Son Remembers,” New York, The Irish Echo, September 22, 2011.

- Hiscock, Earle. “The Longshore Labor Conditions in the Port of Boston,” Naval Architecture Thesis, MIT, 1932.

- Kariotis, Andrew and Valfrid Palmer, “A Study of the Boston Longshoremen,” Thesis for School of Industrial Management, MIT, 1954.

- Marine Board of Investigation. “M/V Black Falcon Explosion, Boston,” November 2, 1953.

- McLaughlin, Francis M. “The Longshoremen’s Strike of 1931: A Conflict Over the Weight of the Sling Load,” Boston College. [no date given]

- McLaughlin, Francis M. “The Replacement of The Knights of Labor by The International Longshoremen’s Association in The Port of Boston,” Historical Journal of Massachusetts, Volume 26, No. 1, 1998.

- Morris, Monica. “How to Become a Longshoreman,” WikiHow.com, September 12, 2022.

- Nelson, Bruce. “Divided We Stand: American Workers and the Struggle for Black Equality,” Princeton University Press, 2002.

- “One Size Fits All” 1960-1970 National Museum of American History.

- Report of the Directors, Port of Boston. “Commonwealth Pier as a Joint Landing Stage,” , November 30, 1914, Public Document No. 9, Boston: Wright & Potter Printing Co., 1915.

- Toledo, Springs. “On the Boston Waterfront,” City Journal, Winter 2017.

Acknowledgments

- Warm thanks to Professor Nicholas A. Juravich, University of Massachusetts, Boston, and Professor Peter Cole of Western Illinois University for their support and expertise.

- Our gratitude to the Perkins School for the Blind and xx for their partnership in creating the audio files.