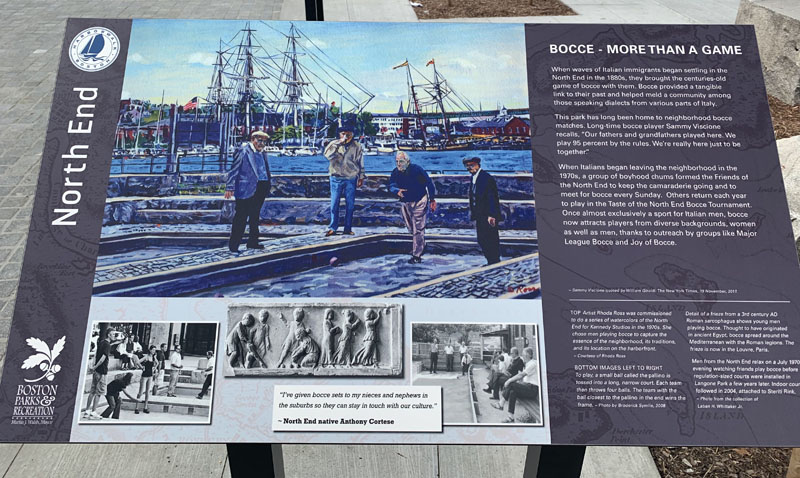

Bocce—more than a game

in the North End

Artist Rhoda Ross was commissioned to do a series of watercolors of the North End for Kennedy Studios in the 1970s. She chose men playing bocce to capture the essence of the neighborhood, its traditions, and its location on the harbor front.

Courtesy of Rhoda Ross

When waves of Italian immigrants began settling in the North End in the 1880s, they brought the centuries-old game of bocce with them. Bocce provided a tangible link to their past and helped meld a community among those speaking dialects from various parts of Italy.

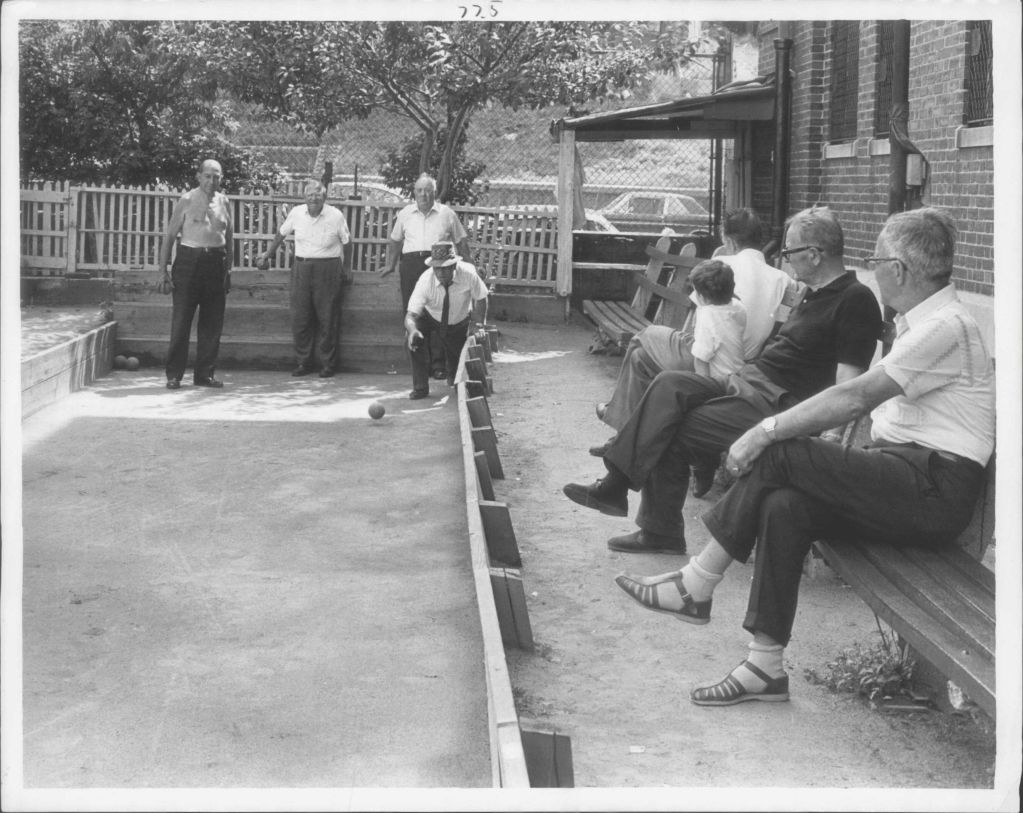

This park has long been home to neighborhood bocce matches. Long-time bocce player Sammy Viscione recalls, “Our fathers and grandfathers played here. We play 95 percent by the rules. We’re really here just to be together.”

When Italians began leaving the neighborhood in the 1970s, a group of boyhood chums formed the Friends of the North End to keep the camaraderie going and to meet for bocce every Sunday. Others return each year to play in the Taste of the North End Bocce Tourna-ment. Once almost exclusively a sport for Italian men, bocce now attracts players from diverse backgrounds, women as well as men, thanks to outreach by groups like Major League Bocce and Joy of Bocce.

To play, a small ball called the pallino is tossed into a long, narrow court. Each team then throws four balls. The team with the ball closest to the pallino in the end wins the frame.

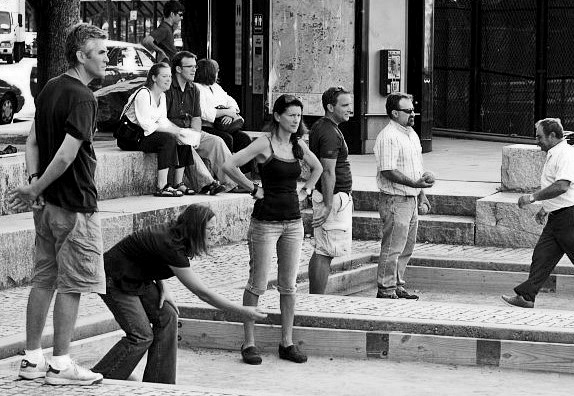

Photo by Broderick Symlie, 2008

“I’ve given bocce sets to my nieces and nephews in the suburbs so they can stay in touch with our culture.” North End native Anthony Cortese

Detail of a frieze from a 3rd century AD Roman sarcophagus shows young men playing bocce. Thought to have originated in ancient Egypt, bocce spread around the Mediterranean with the Roman legions and gave rise to local variations known as boules, pétanque and bowls. The frieze, once part of the Campana Collection in Florence, is now in the Louvre, Paris.

Sign Location

More …

Resources

- Sammy Viscione quoted by William Giraldi. The New York Times, 19 November 2017.

Acknowledgments

- Our gratitude to the Perkins School for the Blind and David W. Cook for their partnership in creating the audio files.

- Thank you to the Boston Marine Society for funding the Spanish and Italian translations as well as the recording of this sign.