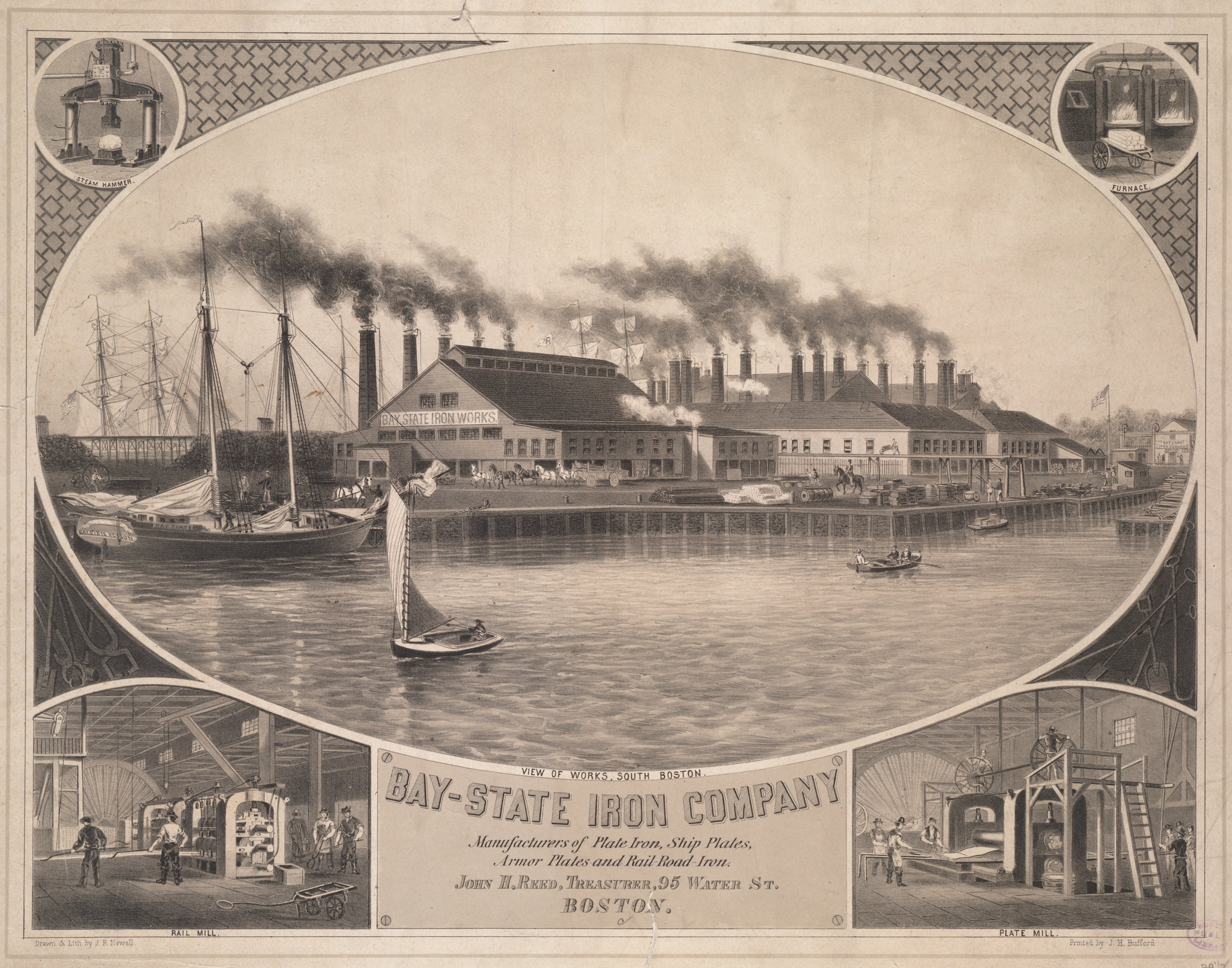

Bay State Iron Company

in South Boston

This 1865 lithograph shows the company’s buildings on this site and details of men manufacturing railroad tracks and iron plates.

Courtesy of the Boston Public Library

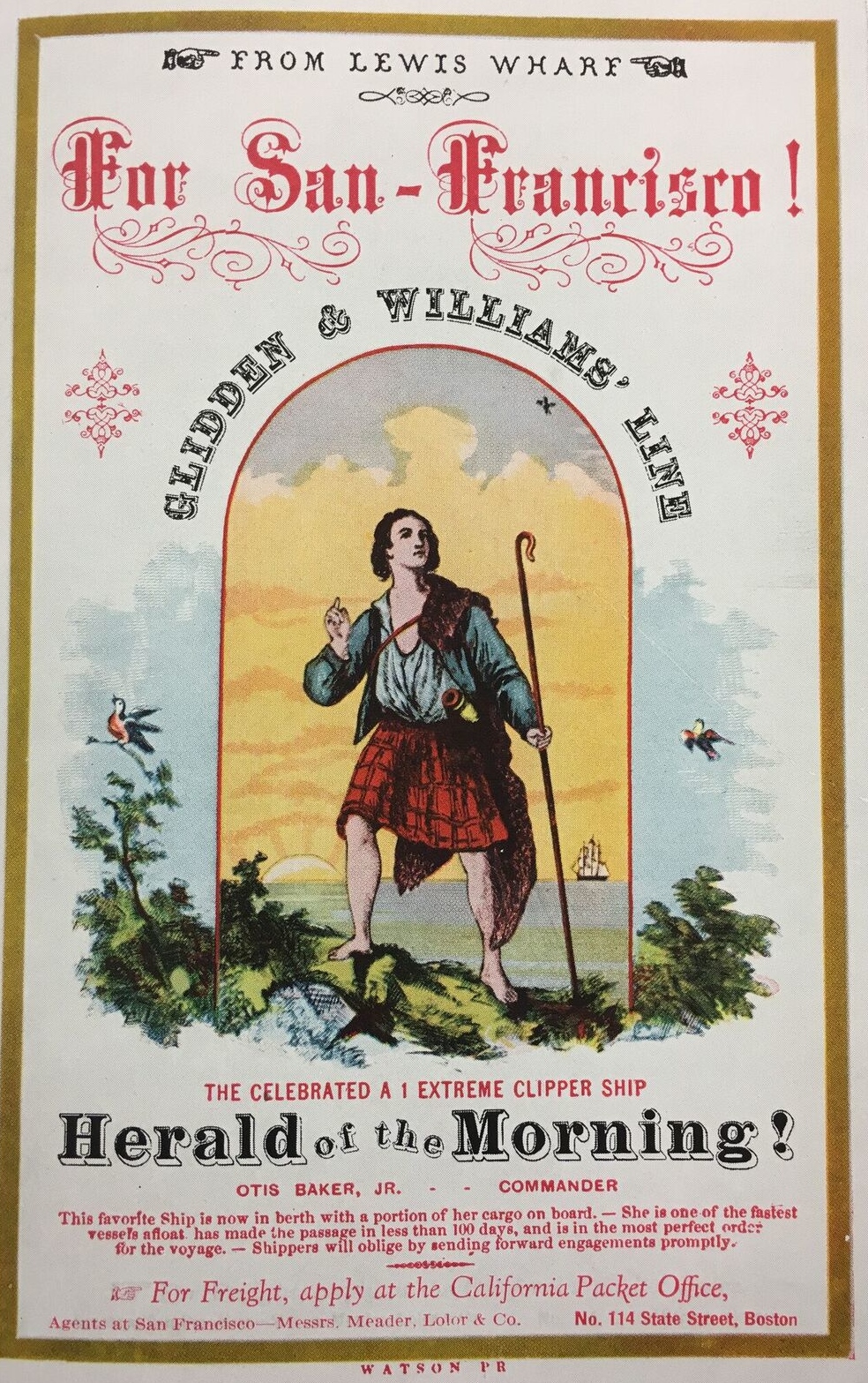

Bay State Iron Company manufactured the first rails Central Pacific Railroad used to construct the western part of the transcontinental railroad. May 16, 1863, clipper ship Herald of the Morning sailed from Boston around Cape Horn to San Francisco, carrying the rails as well as the first locomotive used by the Central Pacific. Upon arrival 127 days later, cargo was transferred onto a schooner for the final leg of the journey to Sacramento. On October 26, men laid the first tracks.

Bay State Iron Company began operations here as a rolling mill in the 1840s. The company shaped wrought iron into railroad tracks, armor, and ship and boiler plates. By 1860, it was described as the largest business of its kind in New England. It employed 300 men and operated around the clock to meet the demand for its products.

The company added innovations like open-hearth steelworks in 1870 and won an award for its boiler plate a few years later. But Bay State Iron struggled financially after the 1873 depression and closed by the end of the 1880s.

Sign Location

More …

Resources

- Huffman, Wendell W. “Railroads Shipped by Sea,” in Railroad History, Bulletin 180, Spring 1999.

- Lesley, J. Peter, The Iron Manufacturer’s Guide to the Furnaces, Forges, and Rolling Mills of the United States. Published by John Wiley, 1859.

- Private and Special Statutes of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, Volume 9.

- Sicilia, David B. “Bay State Iron Company” in Iron and Steel in the Nineteenth Century, ed Paul F. Paskoff. Bruccoli Clark Layman Book, 1989.

- Simonds, Thomas C. History of South Boston: Formerly Dorchester Neck, Now Ward XII of the City of Boston. Published by D. Clapp, 1857.

- Toomey, John & Edward Rankin. History of South Boston (Its Past and Present) and Prospects for the Future. Published in Boston by the authors, 1901.

- about sailing cards & more about sailing cards

- Central Pacific history site

- Sacramento Daily Union “The First Rail Laid” October 27, 1863.

- NPS Historic Handbook “Golden Spike” 2002.

- For more about rolling mills

Acknowledgments

- Sincere thanks to Nancy S. Seasholes for her discovery of the connection between Bay State Iron Works and the Central Pacific Railroad and her steadfast support of our work.

- Our gratitude to the Perkins School for the Blind and David W. Cook for their partnership in creating the audio files.