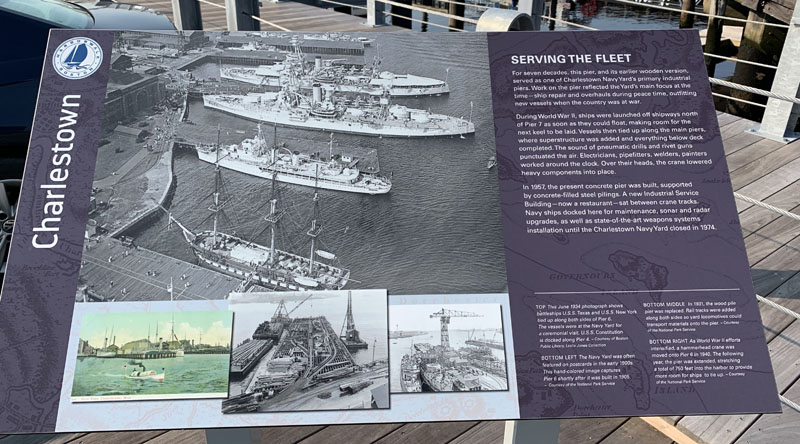

Serving the Fleet

in Charlestown

This June 1934 photograph shows battleships USS Texas and USS New York tied up along both sides of Pier 6. The vessels were at the Navy Yard for a ceremonial visit. U.S.S. Constitution is docked along Pier 4.

Courtesy of Boston Public Library, Leslie Jones Collection

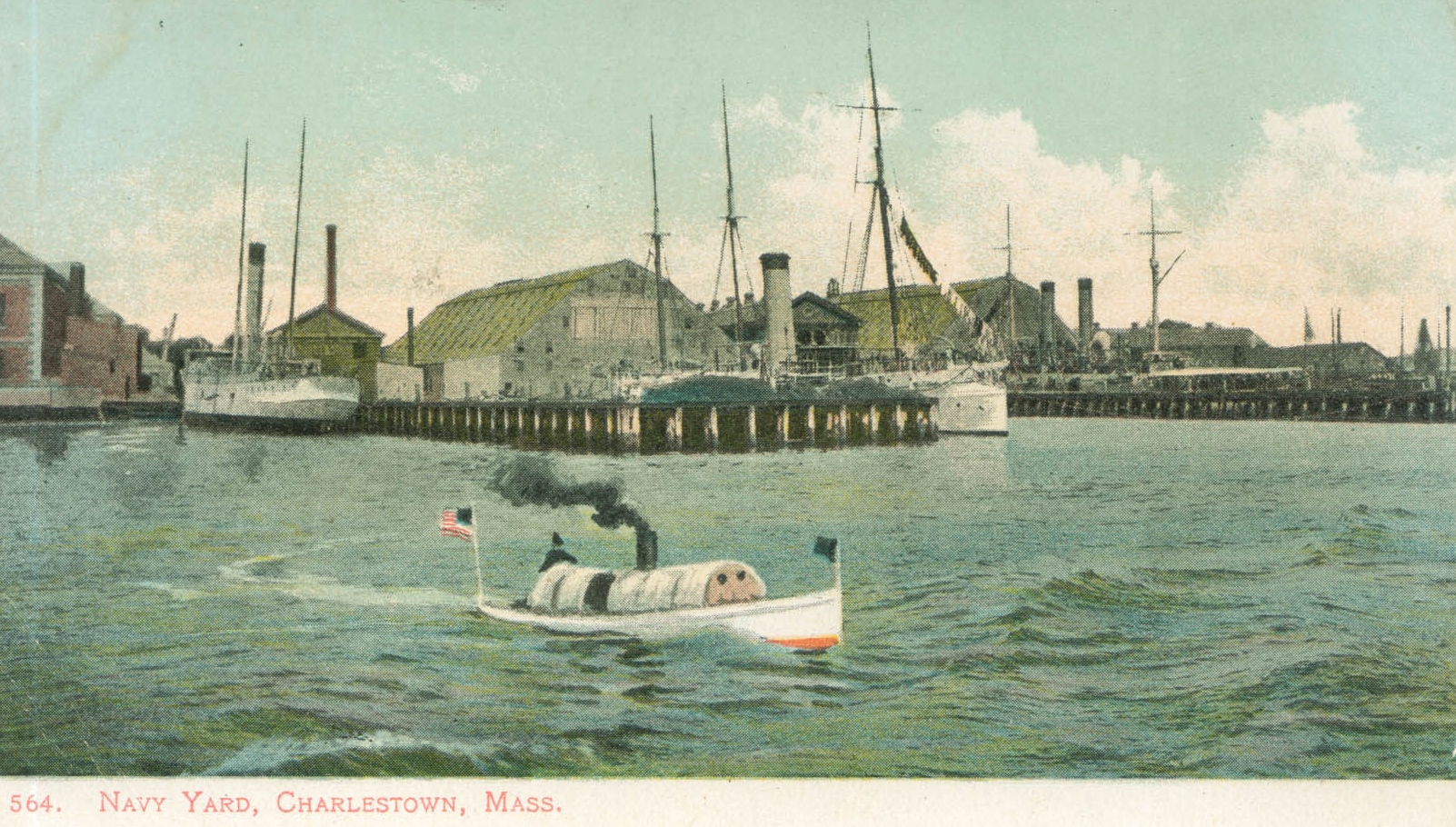

For seven decades, this pier, and its earlier wooden version, served as one of Charlestown Navy Yard’s primary industrial piers. Work on the pier reflected the Yard’s main focus at the time—ship repair and overhauls during peace time, outfitting new vessels when the country was at war.

During World War II, ships were launched off shipways north of Pier 7 as soon as they could float, making room for the next keel to be laid. Vessels then tied up along the main piers, where superstructure was added and everything below deck completed. The sound of pneumatic drills and rivet guns punctuated the air. Electricians, pipefitters, welders, painters worked around the clock. Over their heads, the crane lowered heavy components into place.

In 1957, the present concrete pier was built, supported by concrete-filled steel pilings. A new Industrial Service Building—now a restaurant—sat between crane tracks. Navy ships docked here for maintenance, sonar and radar upgrades, as well as state-of-the-art weapons systems installation until the Charlestown Navy Yard closed in 1974.

Sign Location

More …

Resources

- Bither, Barbara A. and Boston National Historical Park. Images of America: Charlestown Navy Yard. Arcadia Publishing, 1999.

- Carlson, Stephen P., Charlestown Navy Yard Historic Resource Study. National Park Service, U. S. Department of the Interior, 2010.

- Charlestown Navy Yard. Official National Park Handbook. Produced by the Division of Publications National Park Service, 1995.

- “Cultural Landscape Report for Charlestown Navy Yard,” Boston National Historical Park, prepared by Christopher Stevens, Margie Coffin Brown, Ryan Reedy, and Patrick Eleey; Olmsted Center for Landscape Preservation, 2005.

- Interview with David Hannigan, February 2020.

Acknowledgments

- Warm thanks to David Hannigan and Stephen Carlson of the National Park Service for their expertise and support.

- Our gratitude to the Perkins School for the Blind and David W. Cook for their partnership in creating the audio files.